Agile methods have not been widely adopted by enterprises. Agile projects remain, for the most part, independent software development activities, and often by design focused on key areas of enterprise innovation. The latter makes sense, but we should question why Agile concepts should not be rolled out more broadly, because there are considerable opportunities for process improvement across wider range of project classes as well as greater coverage of the end to end life cycle.

If we take this broader, multidimensional view, it should also help enterprises to take a more mature position on agile and agility. Agile methods are primarily guiding management and to an extent project management practices. The business value focus is therefore not surprisingly on “project” quality, cycle time and cost. If we take a broader view we can also focus on enterprise level business improvement, governance and end to end process optimization.

Nobody wants to overload an Agile delivery process unnecessarily. But there are key enterprise perspectives that need to be addressed, and good way to figure out which contribute to the overall delivered agility is to model business value. The business value model allows us to a) develop and refine the solution delivery value chain required for varying enterprise and project contexts and b) charter (structure, manage, govern) architecture and delivery projects with greater probability of achieving optimal outcomes.

Naturally all enterprises and projects have varying needs for business value. Yes, fastest cycle time and lowest cost are always important, but we can imagine that these will be reasonably compromised for the right business improvement, or reduced risk. A good place to start therefore is by considering the agility related business value required for a project, scenario or enterprise in its broadest sense and relate this to delivery life cycle outcomes. In the simple model below I have listed some practice domains and potential outcomes and then mapped these to candidate business benefits.

|

| Agile Outcomes Mapped to Business Value (Example Fragment) |

I have focused Agile practices on Lean process values because these seem to encapsulate all the various Agile methods. In addition I have included disciplines that focus on typical enterprise activities including architecture, asset management, application lifecycle management and automation. I don’t pretend this list is exhaustive, it’s merely illustrative. I am sure readers will have many ideas for practice domains and relevant outcomes. I then mapped this starter list against business benefits using the very effective approach that I cribbed from COBIT5 when I was developing extensions of same. FYI P: Primary, S: Secondary.

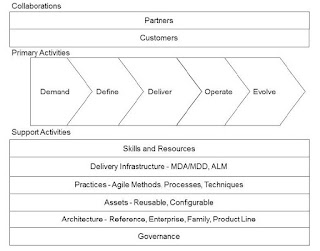

This analysis then provides structured data on which to develop an agility value chain (diagram below). I’m sure readers will be very familiar with this technique, first described by Michael Porter[1]. For further explanation see my introduction in

Realizing the Agile Enterprise.

|

| Agile Enterprise Value Chain |

There are some key points to make about the agile value chain:

1. The primary activities are a cohesive set of activities, and it is important to optimize value across the entire life cycle. For example:

– Addressing software development alone is likely to be suboptimal.

– Making sure that demand is understood, grounded in business strategy, aggregated across lines of business and geographies where appropriate, decomposed into optimal units of work, consolidated into units of release and so on is key.

– Establishing clarity of purpose and matching with an optimal delivery approach.

– Integrating the activities of architecture, definition and delivery in a continuous value chain that minimizes architecture and definition efforts based on value creation.

2. The value of primary activities can be dramatically enhanced with good supporting activity.

3. That supporting capabilities may be delivered using primary activities which either have qualified goals and objectives, or that the outcomes of primary activities are harvested to create supporting capabilities. For example, in the typical enterprise there are frequently considerable benefits to be gained from reusing many types of asset such as services, components, schema, platforms, patterns etc. but it is relatively unusual for enterprises to capitalize on these opportunities for a multitude of reasons including politics, budgets, ownership and support. However if the potential value can be demonstrated and quantified in terms of reduced delivery times and costs, then a business case can be made to put effective systems put in place.

4. Agile concepts do not just relate to software development! There is great opportunity to adopt key Agile concepts including particularly Lean, Kanban and Scrum, across the entire delivery value chain, particularly for primary activities such as demand and define, and supporting activities such as governance, architecture and delivery infrastructure.

5. That few enterprises are independent, and collaborations are part of business as usual. Further, innovative forms of collaboration may be actively pursued relative to the enterprise’s goals, which might result in widespread use of a common platform, business or technology services, or involvement of unconventional partners such as brokers or social networks.

The Value Chain provides a framework for analyzing the relative business value of the capabilities involved in product delivery in terms of agility outcomes. In the table below I have shown just a small fragment of what this might look like. I have decomposed each Value Chain Activity into capabilities and assessed potential agility outcomes. Some very obvious extensions would be to include scoring (weighted support to business level benefits) plus inter capability dependencies. A logical conclusion might be to quantify value in terms of cycle time hours or cost reduction, but this seems unnecessary for our purpose here.

|

Capabilities Mapped to

Agility Outcomes (Example Fragment) |

The detailed Value Chain provides a structured basis for creating and communicating delivery life cycle templates. And it occurs to me this could be just the way to address the elephant in the room for many enterprises – the SDLC standard, commonly a formally mandated standard that is all but ignored by most projects. For most enterprises I believe there are just three basic delivery patterns which provide three template choices, and I will expand on these shortly. I will also be discussing all of the value chain activities in some detail.

Talk to Everware-CBDIabout the Agile Enterprise Workshop. This is currently available as an in-house, intensive workshop. Public scheduled classes will hopefully follow next year.

[1] Porter, M.E. (1985) Competitive Advantage, Free Press, New York, 1985.