Implementing SOA through TOGAF 9.1: the Center Of Excellence

The primary structuring element for SOA applications is a service as distinct from subsystems, systems, or components. A service is an autonomous and discoverable software resource which has a well defined service description.

SOA is based on a fundamental architectural model that defines an interaction model between three primary parties, the service provider, who publishes a service description and provides the implementation for the service, a service consumer, who can either use the uniform resource identifier (URI) for the service description directly or can find the service description in a service registry and bind and invoke the service. The service broker is the third party who provides and maintains the service registry in addition to providing mediation services between providers and consumers.

In 2012, the use of SOA for pivotal emerging technologies, especially for mobile applications and cloud computing, suggests that the future prospect for SOA is favourable. SOA and cloud will begin to fade as differentiating terms because it will just be “the way we do things”. We’re now at the point where everything we deploy is done in a service-oriented way, and cloud is being simply accepted as the delivery platform for applications and services. Also many enterprise architects are wondering if the mobile business model will drive SOA technologies in a new direction. Meanwhile, a close look at mobile application integration today tells us that pressing mobile trends will prompt IT and business leaders to ensure mobile-friendly infrastructure.

To be successful in implementing a SOA initiative, it is highly recommended that a company create a Center of Excellence and the Open Group clearly explains how this can be achieved through the use of TOGAF 9.1. This article is based on the specification and specifically the section (in italics) 22.7.1.3 Partitions and Centers of Excellence with some additional thoughts on sections 22.7.1.1 Principle of Service-Orientation and 22.7.1.2 Governance and Support Strategy.

I have looked at the various attributes and provided further explanations or referred to previous experiences based on existing CoEs or sometimes called Integration Competency Centers.

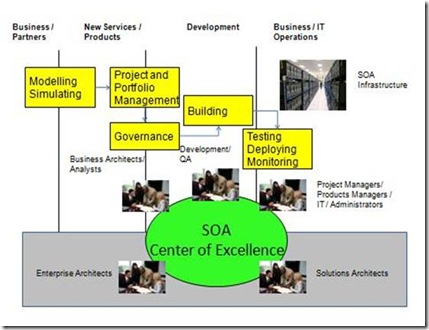

The figure below illustrates below a SOA Center of Excellence as part of the Enterprise Architecture team with domain and solution architects as well as developers, QAs and business architects and analysts coming from a delivery organization.

This center of excellence support methodologies, standards, governance processes and manage a service registry. The main goal of this core group is to establish best practices at design time to maximize reusability of services.

Below is then what is written in the TOGAF 9.1 specification.

A successful CoE will have several key attributes:

- A clear definition of the CoE’s mission: why it exists, its scope of responsibility, and what the organization and the architecture practice should expect from the CoE.

Any SOA Center of Excellence must have a purpose. What do we want to achieve? What are the problems we need to solve?

It may sound obvious, but having a blueprint for SOA is critical. It’s very easy for companies, especially large enterprises with disparate operations, to buy new technologies or integrate applications without regard to how they fit into the overall plan. The challenge in building a SOA is to keep people, including IT and business-side staff focused on the Enterprise Architecture goals.

In order to realize the vision of SOA the following topics should be addressed:

· What to build: A Reference Architecture

· How to build: Service-Oriented Modeling Method

· Whether to build: Assessments, roadmaps, and Maturity evaluations

· Guidance on Building: Architectural and Design patterns

· Oversight: Governance

· How to build: Standards and Tools

The Center of Excellence would first have a vision which could be something like:

“ABCCompany will effectively utilize SOA in order to achieve organizational flexibility and improve responsiveness to our customers”.

Then a mission statement should be communicated across the organization. Below a few examples of mission statements:

“To enable dynamic linkage among application capabilities in a manner that facilitates business effectiveness, maintainability, customer satisfaction, rapid deployment, reuse, performance and successful implementation.”

“The mission of the COE for SOA at ABCCompany is to promote, adopt, support the development and usage of ABCCompany standards, best practices, technologies and knowledge in the field of SOA and have a key role in the business transformation of ABCCompany. The COE will collaborate with the business to create an agile organization, which in turn will facilitate ABCCompany to accelerate the creation of new products and services for the markets, better serve its customers, and better collaborate with partners and vendors.”

The Center of Excellence would also define a structure and the various interactions with

· the enterprise architecture team

· the project management office

· the business process/planning & strategy group

· the product management group

· etc.

And create a steering committee or board (which could be associated to an architecture board).

They will provide different types of support:

· Architecture decision support

o Maintain standards, templates and policies surrounding Integration and SOA

o Participate in Integration and SOA design decisions

· Operational support

o Responsible for building and maintaining SOA Infrastructure

o Purchasing registries and products to grow infrastructure

· Development support

o Development of administrative packages and services

o Develop enterprise services based on strategic direction

- Clear goals for the CoE including measurements and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). It is important to ensure that the measures and KPIs of the CoE do not drive inappropriate selection of SOA as the architecture style.

Measurements and metrics will have to be identified. The common ones could be:

· Service revenue

· Service vitality

· Ratio between services used and those created

· Mean Time To Service Development or Service change

· Service availability

· Service reuse

· Quality assurance

· Etc.

- The CoE will provide the “litmus test” of a good service.

Clearly comprehensive testing activities must be described by the Center of Excellence. In addition to a set of defined processes related to Web Service Definition Language (WSDL) testing, functional unit testing, regression testing, security testing, interoperability testing, vulnerability testing and load, performance testing, an analysis tool suite may be used to tailor the unique testing and validation needs of Service Oriented Architectures.

This helps test the message layer functionality of their services by automating their testing and supports numerous transport protocols including: (here a few examples) HTTP 1.0, HTTP/1.1, JMS, MQ, RMI, SMTP, .NET WCF HTTP, .NET WCF TCP, Electronic Data Interchange, ESBs, etc.

Only by adopting a comprehensive testing stance, enterprises can ensure that their SOA is robust, scalable, interoperable, and secure.

- The CoE will disseminate the skills, experience, and capabilities of the SOA center to the rest of the architecture practice.

The Center of Excellence will promote best practices, methodologies, knowledge, and pragmatic leading-edge solutions in the area of SOA to the project teams.

- Identify how members of the CoE, and other architecture practitioners, will be rewarded for success.

This may sounds like a good idea but I have never seen this as an applied practice.

- Recognition that, at the start, it is unlikely the organization will have the necessary skills to create a fully functional CoE. The necessary skills and experience must be carefully identified, and where they are not present, acquired. A fundamental skill for leading practitioners within the CoE is the ability to mentor other practitioners transferring knowledge, skills, and experience.

Competency and skills building is needed for any initiative. SOA is not just about integrating technologies and applications but it is a culture change within the enterprise which requires IT to move from being a technology provider to a business enabler. There may be a wide range of skills required such as:

· Enterprise Architecture

· Value of SOA

· Governance model for SOA

· Business Process Management and SOA

· Design of SOA solutions

· Modeling

· Technologies and standards

· Security

· Business communication

· Etc.

It has to be said that lack of SOA skills is the number one inhibitor to SOA adoption.

- Close-out plan for when the CoE has fulfilled its purpose.

Here again, I am not sure that I have observed any Center of Excellence being closed…

The Center of Excellence will then also define a Reference Architecture for the organization.

A Reference Architecture is an abstract realization of an architectural model showing how an architectural solution can be built while omitting any reference to specific concrete technologies. Reference Architecture is like an abstract machine. It is built to realize some function and it, in turn, relies on a set of underlying components and capabilities that must be present for it to perform. The capabilities are normally captured into layers which in their own right require an architectural definition. However, the specific choice of the components representing the capabilities is made after various business and feasibility analysis are performed. A Reference Architecture can be used to guide the realization of implementations where specific properties are desired of the concrete system.

The purpose of the Reference Architecture is reflected in the set of requirements that the Reference Architecture must satisfy. We can structure these requirements into a set of goals, a set of critical success factors associated with these goals and a set of requirements that are connected to the critical success factors that ensure their satisfaction.

A Reference Architecture for SOA describes how to build systems according to the principles of SOA. These principles direct IT professionals to design, implement, and deploy information systems from components (i.e. services) that implement discrete business functions. These services can be distributed across geographic and organizational boundaries, can be independently scaled and can be reconfigured into new business processes as needed. This flexibility provides a range of benefits for both IT and business organizations.

Using the pattern approach the SOA Reference Architecture is a means for generating other more specific reference architectures, or even concrete architectures depending on the nature of the patterns. Or to put it another way, it is a machine for generating other machines.

The Open Group Standard for SOA Reference Architecture (SOA RA) is a good way of considering how to build systems.

The center of Excellence needs also to define the SOA life cycle management which consists of various activities such as governing, modelling, assembling, deploying and controlling/monitoring.

Simply put, without management and control, there is no SOA only an “Experience”. The SOA infrastructure must be managed in accordance with the goals and policies of the organization, which include hardware and software IT resource utilization, performance standards as well as goals for service level objectives (SLOs) for the services provided to IT users as well as business goals and policies for businesses that run and use IT. To be truly agile, enactment of all these different types of policies requires automated control that allows goals to be met with only the prescribed level of human interaction.

For every layer of the SOA infrastructure a corresponding Manage and Control component needs to exist / be in place. Moreover, the “manage and control” components must be integrated in a way that they can provide an end-to-end view of the entire SOA infrastructure.

These manage and control functions provide the run-time management and control of the entire enterprise IT execution environment. This includes all of the enterprise’s business processes and information services, including those associated with the IT organization’s own business processes.

The “Principle of Service orientation” must exist as defined in 22.7.1.1 Principle of Service-Orientation, but lower levels of principles, rules, and guidelines are required.

Needs and capabilities are not mechanisms in the SOA Reference Architecture. They are the guiding principles for building and using a particular SOA. Nonetheless, the usefulness of a particular SOA depends on how well the needs and capabilities are defined, understood, and satisfied.

Architecture principles define the underlying general rules and guidelines for the use and deployment of all IT resources and assets across the enterprise. They reflect a level of consensus among the various elements of the enterprise, and form the basis for making future IT decisions.

Guiding principles define the ground rules for development, maintenance, and usage of the SOA. Specific principles for architecture design or service definition, are derived from these guiding principles, focusing on specific themes. These principles are the characteristics that provide the intrinsic behaviour for the style of design.

SOA principles should be clearly related back to the business objectives and key architecture drivers. They will be constructed on the same mode as TOGAF 9.1 principles with the use of statement, rationale and implications. Below examples of the types of services which may be created:

· Put the computing near the data

· Services are technology neutral

· Services are consumable

· Services are autonomous

· Services share a formal contract

· Services are loosely coupled

· Services abstract underlying logic

· Services are reusable

· Services are composable

· Services are stateless

· Services are discoverable

· Location Transparency

· Etc.

Here is a detailed principle example:

· Service invocation

o All service invocations between application silos will be exposed through the Enterprise Service Bus (ESB)

o The only exception to this principle will be when the service meets all the following criteria:

§ It will be used only within the same application silo

§ There is no potential right now or in the near future for re-use of this service

§ The service has already been right-sized

§ The Review Team has approved the exception

As previously indicated, the Center of Excellence would also have to provide guidelines on SOA processes and related technologies. This may include:

· Service analysis (Enterprise Architecture, BPM, OO, requirements and models, UDDI Model)

· Service design (SOAD, specification, Discovery Process, Taxonomy)

· Service provisioning (SPML, contracts, SLA)

· Service implementation development (BPEL, SOAIF)

· Service assembly and integration (JBI, ESB)

· Service testing

· Service deployment (the software on the network)

· Service discovery (UDDI, WSIL, registry)

· Service publishing (SLA, security, certificates, classification, location, UDDI, etc.)

· Service consumption (WSDL, BPEL)

· Service execution (WSDM)

· Service versioning (UDDI, WSDL)

· Service Management and monitoring

· Service operation

· Programming, granularity and abstraction

· Etc.

Other activities may be considered by the Center of Excellence such as providing a collaboration platform, asset management (service are just another type of assets), compliance with standards and best practices, use of guidelines, etc. These activities could also be supported by an Enterprise Architecture team.

As described in TOGAF 9.1, the Center of Excellence can act as the governance body for SOA implementation, work with the Enterprise Architecture team, overseeing what goes into a new architecture that the organization is creating and ensuring that the architecture will meet the current and future needs of the organization.

The Center of Excellence provides expanded opportunities for organizations to leverage and re-use service oriented infrastructure and knowledgebase to facilitate the implementation of cost-effective and timely SOA based solutions.