@antlerboy asks does anyone know theoretical underpinning of the (rather good) police decision-making model?

The National Decision Model (NDM) is a risk assessment framework, or decision making process, that is used by police forces across the UK. It replaces the former Conflict Management Model. Some sources refer to it as the National Decision-Making Model.

Looking around the Internet, I have found two kinds of description of the model – top-down and bottom-up.

The top-down (abstract) description was published by the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) sometime in 2012, and has been replicated in various items of police training material including a page on the College of Policing website. It is fairly abstract, and provides five different stages that officers can follow when making any type of decision – not just conflict management.

Some early responses from the police force regarded the NDM as an ideal model, only weakly connected to the practical reality of decision-making on the ground. See for example The NDM and decision making – what’s the reality? (Inspector Juliet Bravo, April 2012).

In contrast, the bottom-up (context-specific) description emerges when serving police officers discuss using the NDM. According to Mr Google, this discussion tends to focus on one decision in particular – to Taser or not to Taser.

“For me the Taser is a very important link in the National Decision Making Model . It bridges that gap between the baton and the normal firearm that has an almost certain risk of death when used.” (The Peel Blog, July 2012). See also Use of Force – Decision Making (Police Geek, July 2012).

ACPO itself adopts this context-specific perspective in its Questions and Answers on Taser (February 2012, updated July 2013), where it is stated that Taser may be deployed and used as one of a number of tactical options only after application of the National Decision Model (NDM).

Of course, the fact that Taser-related decisions have a high Google ranking doesn’t imply that these decisions represent the most active use of the National Decision Model. The most we can infer from this is that these are the decisions that police and others are most interested in discussing.

(Argyris and Schön introduced the distinction between Espoused Theory and Theory-In-Use. Perhaps we need a third category to refer to what people imagine to be the central or canonical examples of the theory. We might call it Theory-in-View or Theory-in-Gaze.)

In a conflict situation, a police officer often has to decide how much force to use. The officer needs to have a range of tools at his disposal and the ability to select the appropriate tool – in policing, this is known as a use-of-force continuum. More generally, it is an application of the principle of Requisite Variety.

In a particular conflict situation, the police can only use the tools they have at their disposal. The decision to use a Taser can only be taken if the police have the Taser and the training to use it properly. In which case the operational decision must follow the NDM.

More strategic decisions operate on a longer timescale – whether to equip police with certain equipment and training, what rules of engagement to apply, and so on. A truly abstract decision-making model would provide guidance for these strategic decisions as well as the operational decisions.

And that’s exactly what the top-down description of NDM asserts. “It can be applied to spontaneous incidents or planned operations by an individual or team of people, and to both operational and non-operational situations.”

Senior police officers have described the use of the NDM for non-conflict situations. For example, Adrian Lee (Chief Constable of Northants) gave a presentation on the Implications of NDM for Roads Policing (January 2012).

The NDM has also been adapted for use in other organizations. For example, Paul Macfarlane (ex Strathclyde Police) has used the NDM to produced a model aimed at Business Continuity and Risk Management. which he calls Defensive Decision-Making.

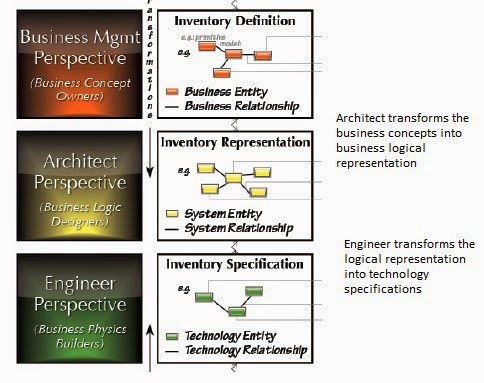

How does the NDM relate to other decision-making models? According to Adrian Lee’s presentation, the NDM is based on three earlier models:

- The Conflict Management Model (CMM). For a discussion from 2011, see Police Oracle.

- The SARA model (Scan, Analyze, Respond, Assess) – which appears to be similar to the OODA loop.

- Something called the PLANE model. (I tried Googling this, and I just got lots of Lego kits. If anyone has a link, please send.)

There is considerable discussion in the USA about the relevance of the OODA loop to policing, and this again focuses on conflict management situations (the “Active Shooter”). There are two important differences between combat (the canonical use of OODA) and conflict management. Firstly, the preferred outcome is not to kill the offender but to disarm him (either physically or psychologically). This means that you sometimes need to give the offender time to calm down, orienting himself into making the right decision.

And the cop needs to stay calm. George “Doc” Thompson, who taught US police a de-escalation technique known as Verbal Judo, once said “We know that the most deadly weapon we carry is not the .45 or the 9mm, it is in fact the cop’s tongue … A single sentence fired off at the wrong person at the wrong time can get you fired, it can get you sued, it can get you killed.”

So it’s not just about having a faster OODA loop than the other guy (although clearly some American cops think this is important). And secondly, there is a lot of talk about situation awareness and anticipation. For example, Dr. Mike Asken, who is a State Police psychologist, has developed a model called AAADA (Anticipating, Alerting, Assessing, Deciding and Acting). There is also a Cognitive OODA model I need to look into.

However, I interpret @antlerboy’s request for theoretical underpinning as not just a historical question (what theories of decision-making were the creators of NDM consciously following) but a methodological question (what theories of decision-making would be relevant to NDM and any other decision models). But this post is already long enough, and the sun is shining outside, so I shall return to this topic another day.

Sources

Michael J. Asken, From OODA to AAADA ― A cycle for surviving violent police encounters (Dec 2010)

Erik P. Blasch et al, User Information Fusion Decision-Making Analysis with the C-OODA Model (Jan 2011)

Tom Dart, ‘Verbal judo’: the police tactic that teaches cops to talk before they shoot (Guardian 21 July 2016)

Adrian Lee, Implications of NDM for Roads Policing (January 2012).

Steve Papenfuhs, The OODA loop, reaction time, and decision making (PoliceOne, 23 February 2012)

National Decision Model (ACPO, 2012?)

National Decision Model (College of Policing, 2013)

SARA model (Center for Problem-Oriented Policing)

Related Posts

National Decision Model and Lessons Learned (Feb 2017)

Updated 28 February 2017