Selling Federal Enterprise Architecture

A taxonomy of subject areas, from which to develop a prioritized marketing and communications plan to evangelize EA activities within and among US Federal Government organizations and constituents.

Any and all feedback is appreciated, particularly in developing and extending this discussion as a tool for use – more information and details are also available.

“Selling” the discipline of Enterprise Architecture (EA) in the Federal Government (particularly in non-DoD agencies) is difficult, notwithstanding the general availability and use of the Federal Enterprise Architecture Framework (FEAF) for some time now, and the relatively mature use of the reference models in the OMB Capital Planning and Investment (CPIC) cycles. EA in the Federal Government also tends to be a very esoteric and hard to decipher conversation – early apologies to those who agree to continue reading this somewhat lengthy article.

Alignment to the FEAF and OMB compliance mandates is long underway across the Federal Departments and Agencies (and visible via tools like PortfolioStat and ITDashboard.gov – but there is still a gap between the top-down compliance directives and enablement programs, and the bottom-up awareness and effective use of EA for either IT investment management or actual mission effectiveness. “EA isn’t getting deep enough penetration into programs, components, sub-agencies, etc.”, verified a panelist at the most recent EA Government Conference in DC.

Newer guidance from OMB may be especially difficult to handle, where bottom-up input can’t be accurately aligned, analyzed and reported via standardized EA discipline at the Agency level – for example in addressing the new (for FY13) Exhibit 53D “Agency IT Reductions and Reinvestments” and the information required for “Cloud Computing Alternatives Evaluation” (supporting the new Exhibit 53C, “Agency Cloud Computing Portfolio”).

Therefore, EA must be “sold” directly to the communities that matter, from a coordinated, proactive messaging perspective that takes BOTH the Program-level value drivers AND the broader Agency mission and IT maturity context into consideration.

Selling EA means persuading others to take additional time and possibly assign additional resources, for a mix of direct and indirect benefits – many of which aren’t likely to be realized in the short-term. This means there’s probably little current, allocated budget to work with; ergo the challenge of trying to sell an “unfunded mandate”.

Also, the concept of “Enterprise” in large Departments like Homeland Security tends to cross all kinds of organizational boundaries – as Richard Spires recently indicated by commenting that “…organizational boundaries still trump functional similarities. Most people understand what we’re trying to do internally, and at a high level they get it. The problem, of course, is when you get down to them and their system and the fact that you’re going to be touching them…there’s always that fear factor,” Spires said.

It is quite clear to the Federal IT Investment community that for EA to meet its objective, understandable, relevant value must be measured and reported using a repeatable method – as described by GAO’s recent report “Enterprise Architecture Value Needs To Be Measured and Reported“.

What’s not clear is the method or guidance to sell this value. In fact, the current GAO “Framework for Assessing and Improving Enterprise Architecture Management (Version 2.0)”, a.k.a. the “EAMMF”, does not include words like “sell”, “persuade”, “market”, etc., except in reference (“within Core Element 19: Organization business owner and CXO representatives are actively engaged in architecture development”) to a brief section in the CIO Council’s 2001 “Practical Guide to Federal Enterprise Architecture”, entitled “3.3.1. Develop an EA Marketing Strategy and Communications Plan.” Furthermore, Core Element 19 of the EAMMF is advised to be applied in “Stage 3: Developing Initial EA Versions”. This kind of EA sales campaign truly should start much earlier in the maturity progress, i.e. in Stages 0 or 1.

So, what are the understandable, relevant benefits (or value) to sell, that can find an agreeable, participatory audience, and can pave the way towards success of a longer-term, funded set of EA mechanisms that can be methodically measured and reported? Pragmatic benefits from a useful EA that can help overcome the fear of change? And how should they be sold?

Following is a brief taxonomy (it’s a taxonomy, to help organize SME support) of benefit-related subjects that might make the most sense, in creating the messages and organizing an initial “engagement plan” for evangelizing EA “from within”. An EA “Sales Taxonomy” of sorts. We’re not boiling the ocean here; the subjects that are included are ones that currently appear to be urgently relevant to the current Federal IT Investment landscape.

Note that successful dialogue in these topics is directly usable as input or guidance for actually developing early-stage, “Fit-for-Purpose” (a DoDAF term) Enterprise Architecture artifacts, as prescribed by common methods found in most EA methodologies, including FEAF, TOGAF, DoDAF and our own Oracle Enterprise Architecture Framework (OEAF).

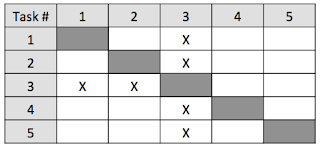

The taxonomy below is organized by (1) Target Community, (2) Benefit or Value, and (3) EA Program Facet – as in:

“Let’s talk to (1: Community Member) about how and why (3: EA Facet) the EA program can help with (2: Benefit/Value)”.

Once the initial discussion targets and subjects are approved (that can be measured and reported), a “marketing and communications plan” can be created.

A working example follows the Taxonomy.

Enterprise Architecture Sales Taxonomy

Draft, Summary Version

1. Community

1.1. Budgeted Programs or Portfolios

Communities of Purpose (CoPR)

1.1.1. Program/System Owners (Senior Execs) Creating or Executing Acquisition Plans

1.1.2. Program/System Owners Facing Strategic Change

1.1.2.1. Mandated

1.1.2.2. Expected/Anticipated

1.1.3. Program Managers – Creating Employee Performance Plans

1.1.4. CO/COTRs – Creating Contractor Performance Plans, or evaluating Value Engineering Change Proposals (VECP)

1.2. Governance & Communications

Communities of Practice (CoP)

1.2.1. Policy Owners

1.2.1.1. OCFO

1.2.1.1.1. Budget/Procurement Office

1.2.1.1.2. Strategic Planning

1.2.1.2. OCIO

1.2.1.2.1. IT Management

1.2.1.2.2. IT Operations

1.2.1.2.3. Information Assurance (Cyber Security)

1.2.1.2.4. IT Innovation

1.2.1.3. Information-Sharing/ Process Collaboration (i.e. policies and procedures regarding Partners, Agreements)

1.2.2. Governing IT Council/SME Peers (i.e. an “Architects Council”)

1.2.2.1. Enterprise Architects (assumes others exist; also assumes EA participants aren’t buried solely within the CIO shop)

1.2.2.2. Domain, Enclave, Segment Architects – i.e. the right affinity group for a “shared services” EA structure (per the EAMMF), which may be classified as Federated, Segmented, Service-Oriented, or Extended

1.2.2.3. External Oversight/Constraints

1.2.2.3.1. GAO/OIG & Legal

1.2.2.3.2. Industry Standards

1.2.2.3.3. Official public notification, response

1.2.3. Mission Constituents

Participant & Analyst Community of Interest (CoI)

1.2.3.1. Mission Operators/Users

1.2.3.2. Public Constituents

1.2.3.3. Industry Advisory Groups, Stakeholders

1.2.3.4. Media

2. Benefit/Value

(Note the actual benefits may not be discretely attributable to EA alone; EA is a very collaborative, cross-cutting discipline.)

2.1. Program Costs – EA enables sound decisions regarding…

2.1.1. Cost Avoidance – a TCO theme

2.1.2. Sequencing – alignment of capability delivery

2.1.3. Budget Instability – a Federal reality

2.2. Investment Capital – EA illuminates new investment resources via…

2.2.1. Value Engineering – contractor-driven cost savings on existing budgets, direct or collateral

2.2.2. Reuse – reuse of investments between programs can result in savings, chargeback models; avoiding duplication

2.2.3. License Refactoring – IT license & support models may not reflect actual or intended usage

2.3. Contextual Knowledge – EA enables informed decisions by revealing…

2.3.1. Common Operating Picture (COP) – i.e. cross-program impacts and synergy, relative to context

2.3.2. Expertise & Skill – who truly should be involved in architectural decisions, both business and IT

2.3.3. Influence – the impact of politics and relationships can be examined

2.3.4. Disruptive Technologies – new technologies may reduce costs or mitigate risk in unanticipated ways

2.3.5. What-If Scenarios – can become much more refined, current, verifiable; basis for Target Architectures

2.4. Mission Performance – EA enables beneficial decision results regarding…

2.4.1. IT Performance and Optimization – towards 100% effective, available resource utilization

2.4.2. IT Stability – towards 100%, real-time uptime

2.4.3. Agility – responding to rapid changes in mission

2.4.4. Outcomes –measures of mission success, KPIs – vs. only “Outputs”

2.4.5. Constraints – appropriate response to constraints

2.4.6. Personnel Performance – better line-of-sight through performance plans to mission outcome

2.5. Mission Risk Mitigation – EA mitigates decision risks in terms of…

2.5.1. Compliance – all the right boxes are checked

2.5.2. Dependencies –cross-agency, segment, government

2.5.3. Transparency – risks, impact and resource utilization are illuminated quickly, comprehensively

2.5.4. Threats and Vulnerabilities – current, realistic awareness and profiles

2.5.5. Consequences – realization of risk can be mapped as a series of consequences, from earlier decisions or new decisions required for current issues

2.5.5.1. Unanticipated – illuminating signals of future or non-symmetric risk; helping to “future-proof”

2.5.5.2. Anticipated – discovering the level of impact that matters

3. EA Program Facet

(What parts of the EA can and should be communicated, using business or mission terms?)

3.1. Architecture Models – the visual tools to be created and used

3.1.1. Operating Architecture – the Business Operating Model/Architecture elements of the EA truly drive all other elements, plus expose communication channels

3.1.2. Use Of – how can the EA models be used, and how are they populated, from a reasonable, pragmatic yet compliant perspective? What are the core/minimal models required? What’s the relationship of these models, with existing system models?

3.1.3. Scope – what level of granularity within the models, and what level of abstraction across the models, is likely to be most effective and useful?

3.2. Traceability – the maturity, status, completeness of the tools

3.2.1. Status – what in fact is the degree of maturity across the integrated EA model and other relevant governance models, and who may already be benefiting from it?

3.2.2. Visibility – how does the EA visibly and effectively prove IT investment performance goals are being reached, with positive mission outcome?

3.3. Governance – what’s the interaction, participation method; how are the tools used?

3.3.1. Contributions – how is the EA program informed, accept submissions, collect data? Who are the experts?

3.3.2. Review – how is the EA validated, against what criteria?

Taxonomy Usage Example:

1. To speak with:

a. …a particular set of System Owners Facing Strategic Change, via mandate (like the “Cloud First” mandate); about…

b. …how the EA program’s visible and easily accessible Infrastructure Reference Model (i.e. “IRM” or “TRM”), if updated more completely with current system data, can…

c. …help shed light on ways to mitigate risks and avoid future costs associated with NOT leveraging potentially-available shared services across the enterprise…

2. ….the following Marketing & Communications (Sales) Plan can be constructed:

a. Create an easy-to-read “Consequence Model” that illustrates how adoption of a cloud capability (like elastic operational storage) can enable rapid and durable compliance with the mandate – using EA traceability. Traceability might be from the IRM to the ARM (that identifies reusable services invoking the elastic storage), and then to the PRM with performance measures (such as % utilization of purchased storage allocation) included in the OMB Exhibits; and

b. Schedule a meeting with the Program Owners, timed during their Acquisition Strategy meetings in response to the mandate, to use the “Consequence Model” for advising them to organize a rapid and relevant RFI solicitation for this cloud capability (regarding alternatives for sourcing elastic operational storage); and

c. Schedule a series of short “Discovery” meetings with the system architecture leads (as agreed by the Program Owners), to further populate/validate the “As-Is” models and frame the “To Be” models (via scenarios), to better inform the RFI, obtain the best feedback from the vendor community, and provide potential value for and avoid impact to all other programs and systems.

–end example —

Note that communications with the intended audience should take a page out of the standard “Search Engine Optimization” (SEO) playbook, using keywords and phrases relating to “value” and “outcome” vs. “compliance” and “output”. Searches in email boxes, internal and external search engines for phrases like “cost avoidance strategies”, “mission performance metrics” and “innovation funding” should yield messages and content from the EA team.

This targeted, informed, practical sales approach should result in additional buy-in and participation, additional EA information contribution and model validation, development of more SMEs and quick “proof points” (with real-life testing) to bolster the case for EA. The proof point here is a successful, timely procurement that satisfies not only the external mandate and external oversight review, but also meets internal EA compliance/conformance goals and therefore is more transparently useful across the community.

In short, if sold effectively, the EA will perform and be recognized. EA won’t therefore be used only for compliance, but also (according to a validated, stated purpose) to directly influence decisions and outcomes.

The opinions, views and analysis expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Oracle.