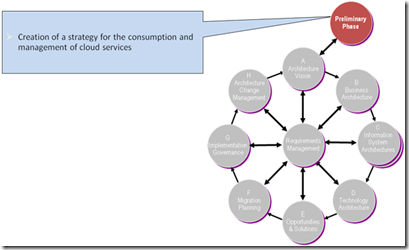

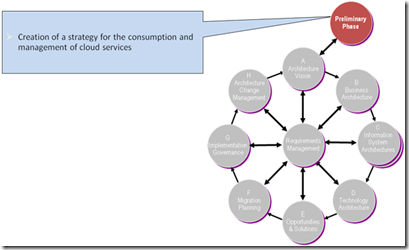

In a previous article I described the need to define a strategy as an additional step in the TOGAF 9 Preliminary Phase. This article describes in more details what could be the content of such a document, what are the governance activities related to the Consumption and Management of Cloud Services.

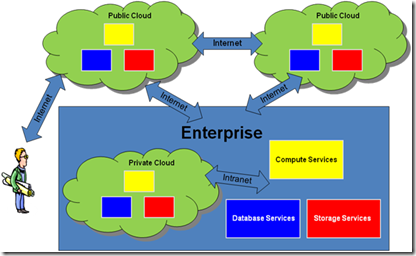

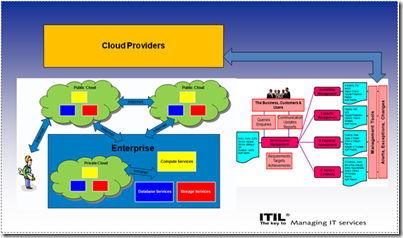

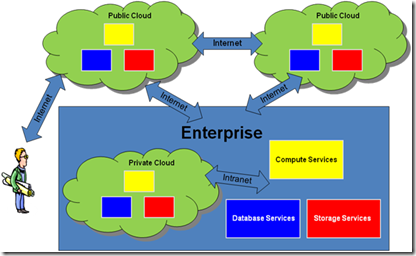

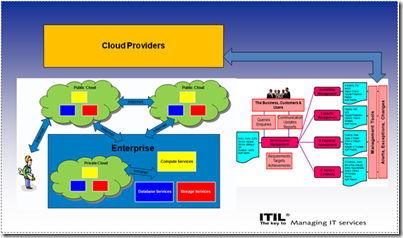

Before deciding to switch over to Cloud Computing, companies should first fully understand the concepts and implications of an internal IT investment or buying this as a service. There are different approaches which may have to be considered from an enterprise level when Cloud computing is considered: Public Cloud vs Private Clouds vs Hybrid Clouds. Despite the fact that many people already know what the differences are, below some summary of the various models

· A public Cloud is one in which the consumer of Cloud services and the provider of cloud services exist in separate enterprises. The ownership of the assets used to deliver cloud services remains with the provider

· A private Cloud is one in which both the consumer of Cloud services and the provider of those services exist within the same enterprise. The ownership of the Cloud assets resides within the same enterprise providing and consuming cloud services. It is really a description of a highly virtualized, on-premise data center that is behaving as if it were that of a public cloud provider

· A hybrid Cloud combines multiple elements of public and private cloud, including any combination of providers and consumers

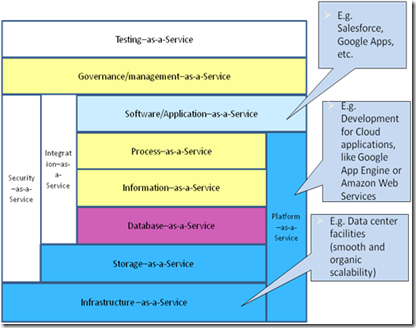

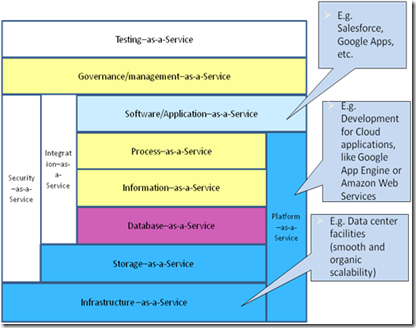

Once the major Business stakeholders understand the concepts, some initial decisions may have to be documented and included in that document. The same may also apply to the various Cloud Computing categorisations such as diagrammed below:

The categories the enterprise may be interested in related to existing problems can already be included as a section in that document.

Quality Management

There is need of a system for evaluating performance, whether in the delivery of Cloud services or the quality of products provided to consumers, or customers. This may include:

· A test planning and a test asset management from Business requirements to defects

· A Project governance and release decisions based on some standards such as Prince 2/PMI and ITIL

· A Data quality control (all data uploaded to a Cloud computing service provider must ensure it fits the requirements of the provider). This should be detailed and provided by the provider

· Detailed and documented Business Processes as defined in ISO 9001:

o Systematically defining the activities necessary to obtain a desired result

o Establishing clear responsibility and accountability for managing key activities

o Analyzing and measuring of the capability of key activities

o Identifying the interfaces of key activities within and between the functions of the organization

o Focusing on the factors such as resources, methods, and materials that will improve key activities of the organization

o Evaluating risks, consequences and impacts of activities on customers, suppliers and other interested parties

Security Management

This would address and document specific topics such as:

· Eliminating the need to constantly reconfigure static security infrastructure for a dynamic computing environment

· Define how services are able to securely connect and reliably communicate with internal IT services and other public services

· Penetration security checks

· How a Security Management/System Management/Network Management teams monitor that security and the availability

Semantic Management

The amount of unstructured electronic information in enterprise environments is growing rapidly. Business people have to collaboratively realise the reconciliation of their heterogeneous metadata and consequently the application of the derived business semantic patterns to establish alignment between the underlying data structures. The way this will be handled may also be included.

IT Service Management (ITIL)

IT Service Management or IT Operations teams will have to address many new challenges due to the Cloud. This will need to be addressed for some specific processes such as:

· Incident Management

o The Cloud provider must ensure that all outages or exceptions to normal operations are resolved as quickly as possible while capturing all of the details for the actions that were taken and are communicated to the customer.

· Change Management

o Strict change management practices must be adhered to and all changes implemented during approved maintenance windows must be tracked, monitored, and validated.

· Configuration Management (Service Asset and…)

o Companies who have a CMDB must provide this to the Cloud providers with detailed descriptions of the relationships between configuration items (CI)

o CI relationships empowers change and incident managers need to determine that a modification to one service may impact several other related services and the components of those services

o This provides more visibility into the Cloud environment, allowing consumers and providers to make more informed decisions not only when preparing for a change but also when diagnosing incidents and problems

· Problem Management

o The Cloud provider needs to identify the root cause analysis in case or problems

· Service Level Management

o Service Level Agreements (or Underpinning contracts) must be transparent and accessible to the end users. The business representatives should be negotiating these agreements. They will need to effectively negotiate commercial, technical, and legal terms. It will be important to establish these concrete, measurable Service Level Agreements (SLAs) without these and an effective means for verifying compliance, the damage from poor service levels will only be exacerbated

· Vendors Management

o Relationship between a vendor and their customers changes

o Contractual arrangements

· Capacity Management and Availability Management

o Reporting on performance

Other activities must be documented such as:

Monitoring

· Monitoring will be a very important activity and should be described in the Strategy document. The assets and infrastructure that make up the Cloud service is not within the enterprise. They are owned by the Cloud providers, which will most likely have a focus on maximizing their revenue, not necessarily optimizing the performance and availability of the enterprise’s services. Establishing sound monitoring practices for the cloud services from the outset will bring significant benefits in the long term. Outsourcing delivery of service does not necessarily imply that we can outsource the monitoring of that service. Besides, today very few cloud providers are offering any form of service level monitoring to their customers. Quite often, they are providing the Cloud service but not proving that they are providing that service.

· The resource usage and consumption must be monitored and managed in order to support strategic decision making

· Whenever possible, the Cloud providers should furnish the relevant tools for management and reporting and take away the onerous tasks of patch management, version upgrades, high availability, disaster recovery and the like. This obviously will impact IT Service Continuity for the enterprise.

· Service Measurement, Service Reporting and Service Improvement processes must be considered.

Consumption and costs

· Service usage (when and how) to determine the intrinsic value that the service is providing to the Business, and IT can also use this information to compute the Return On Investment for their Cloud computing initiatives and related services. This would be related to the process IT Financial Management.

Risk Management

The TOGAF 9 risk management method should be considered to address the various risks associated such as:

· Ownership, Cost, Scope, Provider relationship, Complexity, Contractual, Client acceptance, etc

· Other risks should also be considered such as : Usability, Security (obviously…) and Interoperability

Asset Management and License Management

When various cloud approaches are considered (services on-premise via the Cloud), hardware and software license management to be defined to ensure companies can meet their governance and contractual requirements

Transactions

Ensuring the safety of confidential data is a mission critical aspect of the business. Cloud computing gives them concerns over the lack of control that they will have over company data, and does not enable them to monitor the processes used to organize the information.

Being able to manage the transactions in the Cloud is vital and Business transaction safety should be considered (recording, tracking, alerts, electronic signatures, etc…).

There may be other aspects which should be integrated in this Strategy document that may vary according to the level of maturity of the enterprise or existing best practices in use.

When considering Cloud computing, the Preliminary phase will include in the definition of the Architecture Governance Framework most of the touch points with other processes as described above. At completion, touch-points and impacts should be clearly understood and agreed by all relevant stakeholders.