Architect or Coach?

Is it just me, or are others finding the Enterprise Architect role shifting towards ‘Coach/Facilitator’?

Is it just me, or are others finding the Enterprise Architect role shifting towards ‘Coach/Facilitator’? Aggregated enterprise architecture wisdom

Is it just me, or are others finding the Enterprise Architect role shifting towards ‘Coach/Facilitator’?

Is it just me, or are others finding the Enterprise Architect role shifting towards ‘Coach/Facilitator’? You’re not being clear. I need you to be clear.

I have no idea what you’re saying. Are you asking me to do something? Is this informational? Why did I get this?

Having a reasonable command of the Engrish language, I fully understand each…

You’re not being clear. I need you to be clear.

I have no idea what you’re saying. Are you asking me to do something? Is this informational? Why did I get this?

Having a reasonable command of the Engrish language, I fully understand each…

In his blog Richard Veryard relates how the public sector, in the UK at least, is moving slowly towards understanding the impact of Digital Government. He reports on a workshop he attended recently to discuss some of the architectural aspects of Digita…

In his blog Richard Veryard relates how the public sector, in the UK at least, is moving slowly towards understanding the impact of Digital Government. He reports on a workshop he attended recently to discuss some of the architectural aspects of Digita…

Are you too old to be innovative? I don’t mean, are you able to figure things out like the TV remote, or the microwave, or email. I mean, are you too old to be truly innovative.

A report by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) indicates…

Are you too old to be innovative? I don’t mean, are you able to figure things out like the TV remote, or the microwave, or email. I mean, are you too old to be truly innovative.A report by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) indicates that …

#diggovreview #publicsectorIT .

Attended an interesting workshop last week to discuss some of the architectural aspects of Digital Government, hosted by Skyscape. One purpose of this discussion was to feed into the Labour Party Digital Government Review, and possibly into the Labour manifesto for the next election. Under modified Chatham House rules, I believe I am permitted to blog about the workshop as long as I don’t attribute anything to anybody or any organization.

There are several architectural themes that are probably shared between the political parties, although there may be some differences of emphasis and interpretation. For example, everyone seems to pay lip service to the idea of opening up public sector IT, and reducing the power of the incompetent and self-interested, whoever these may be. But there will undoubtedly be different views on the right tactics for redistributing commercial and bureaucratic power.

Openness leads to fashionable ideas about IT acquisition – a preference for consuming rather than self-build, and a preference for agile development rather than waterfall. These are great ideas when used properly, but we must be careful not to encourage the illusion that these ideas provide a magic solution to the troubles of public sector IT. Indeed, some recent IT disasters have been attributed to an ill-considered rush to “Agile”. And the Buy-Not-Build agenda must be governed properly, to avoid ceding too much architectural control to the large platform providers.

Openness also means structural change. For example, a shift from vertical integration and vertical silos to lateral modularity and co-creation, which my friend and associate Philip Boxer calls Collaborative Composition. This connects with the notions of Shared Services and Platform.

Finally, there is the question of the tempo of change. Government policies have a fairly rapid cycle time – in some cases around 18-24 months depending on department – but we cannot afford to reengineer systems and services, let alone platforms, at this sort of frequency.

So there was considerable discussion about the role of Government in providing a platform, and whether the platform should be a Minimum Viable Platform (similar to the Internet) or provide added value. There was also some debate as to whether politicians could be persuaded to support systems and platforms that would last longer than the policies that they were intended to implement.

The Public Sector suffers, perhaps even more than other organizations, from a confusion between Requirement and Solution. So people like to talk about Open Standards or Agile as the solution to high IT costs, or advocate Big Central Database as the perfect solution to any information needs, instead of talking about the requirements, such as interoperability and low switching costs. I hope that the Labour Party (or any other party for that matter) can be encouraged to express its policies in terms of the requirements and governance approach, rather than mandating specific technological solutions.

As I’ve pointed out before, the term “Joined-Up Government” has several different interpretations. From an Inside-Out (supply-side) perspective, it is commonly taken to imply improved integration between separate government departments and agencies – in other words, some kind of reorganization, not merely of IT systems and services but also the agencies responsible for these services. Of course, reorganization might sometimes be needed, but this is merely one possible solution to the real requirement, which in my opinion comes from the Outside-In (demand-side) perspective – the citizen’s need for a coherent experience of government services.

For example, the much-discussed integration between Healthcare and Social Care doesn’t entail merging two massive and inefficient silos into one even more massive and inefficient silo, but could be achieved simply by opening up the silos and improving the flows of information between them. The Outside-In perspective merely calls for the citizen to get a coherent joined-up service across both healthcare and social care, however this may be done.

And consider the much maligned Contact Point, which had somehow morphed from an information sharing platform (“System of Engagement”) to a Big Central Database (“System of Record”), largely under the control of people who didn’t appreciate that these weren’t necessarily the same thing.

Effective multi-agency working depends on effective information sharing, but this doesn’t mean putting all the data into a single source of truth. Many of the breakthroughs of Digital Government have come, not from building massive central databases, but from improving collaboration between different agencies – health, social care, police, justice, etc – often dealing with the same problem families from different professional perspectives. As we say at Glue Reply, it’s about the conversation.

Some of us have been talking about these themes for a long time. In my own small way, I have written a number of articles and blogposts about eGovernment and Joined-Up Government, and I submitted something on Shared Services to the Cabinet Office in January 2006, most of which is probably still valid. See previous posts on this blog – eGovernment, Joined-Up, Shared Services.

Philip Boxer, Creating Value in Ecosystems (December 2010)

Jerry Fishenden and Mark Thompson, Digital Government, Open Architecture, and Innovation: Why Public Sector IT Will Never Be the Same Again (Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory September 2012)

Mike Martin, Open Architecture Critique – A Draft (March 2014)

David Sprott and Richard Veryard, Shared Services for the UK Public Sector (Submission to the Cabinet Office, CBDI Forum January 2006)

Richard Veryard, Joined-Up Services (Review of the Public Management and Policy Association. February 2002)

Richard Veryard and Philip Boxer, Public Sector IT – The CSA Case (December 2004)

See also David Sprott’s response to this post. Open Architecture for the Public Sector (May 2014)

#diggovreview #publicsectorIT .

Attended an interesting workshop last week to discuss some of the architectural aspects of Digital Government, hosted by Skyscape. One purpose of this discussion was to feed into the Labour Party Digital Government Review, and possibly into the Labour manifesto for the next election. Under modified Chatham House rules, I believe I am permitted to blog about the workshop as long as I don’t attribute anything to anybody or any organization.

There are several architectural themes that are probably shared between the political parties, although there may be some differences of emphasis and interpretation. For example, everyone seems to pay lip service to the idea of opening up public sector IT, and reducing the power of the incompetent and self-interested, whoever these may be. But there will undoubtedly be different views on the right tactics for redistributing commercial and bureaucratic power.

Openness leads to fashionable ideas about IT acquisition – a preference for consuming rather than self-build, and a preference for agile development rather than waterfall. These are great ideas when used properly, but we must be careful not to encourage the illusion that these ideas provide a magic solution to the troubles of public sector IT. Indeed, some recent IT disasters have been attributed to an ill-considered rush to “Agile”. And the Buy-Not-Build agenda must be governed properly, to avoid ceding too much architectural control to the large platform providers.

Openness also means structural change. For example, a shift from vertical integration and vertical silos to lateral modularity and co-creation, which my friend and associate Philip Boxer calls Collaborative Composition. This connects with the notions of Shared Services and Platform.

Finally, there is the question of the tempo of change. Government policies have a fairly rapid cycle time – in some cases around 18-24 months depending on department – but we cannot afford to reengineer systems and services, let alone platforms, at this sort of frequency.

So there was considerable discussion about the role of Government in providing a platform, and whether the platform should be a Minimum Viable Platform (similar to the Internet) or provide added value. There was also some debate as to whether politicians could be persuaded to support systems and platforms that would last longer than the policies that they were intended to implement.

The Public Sector suffers, perhaps even more than other organizations, from a confusion between Requirement and Solution. So people like to talk about Open Standards or Agile as the solution to high IT costs, or advocate Big Central Database as the perfect solution to any information needs, instead of talking about the requirements, such as interoperability and low switching costs. I hope that the Labour Party (or any other party for that matter) can be encouraged to express its policies in terms of the requirements and governance approach, rather than mandating specific technological solutions.

As I’ve pointed out before, the term “Joined-Up Government” has several different interpretations. From an Inside-Out (supply-side) perspective, it is commonly taken to imply improved integration between separate government departments and agencies – in other words, some kind of reorganization, not merely of IT systems and services but also the agencies responsible for these services. Of course, reorganization might sometimes be needed, but this is merely one possible solution to the real requirement, which in my opinion comes from the Outside-In (demand-side) perspective – the citizen’s need for a coherent experience of government services.

For example, the much-discussed integration between Healthcare and Social Care doesn’t entail merging two massive and inefficient silos into one even more massive and inefficient silo, but could be achieved simply by opening up the silos and improving the flows of information between them. The Outside-In perspective merely calls for the citizen to get a coherent joined-up service across both healthcare and social care, however this may be done.

And consider the much maligned Contact Point, which had somehow morphed from an information sharing platform (“System of Engagement”) to a Big Central Database (“System of Record”), largely under the control of people who didn’t appreciate that these weren’t necessarily the same thing.

Effective multi-agency working depends on effective information sharing, but this doesn’t mean putting all the data into a single source of truth. Many of the breakthroughs of Digital Government have come, not from building massive central databases, but from improving collaboration between different agencies – health, social care, police, justice, etc – often dealing with the same problem families from different professional perspectives. As we say at Glue Reply, it’s about the conversation.

Some of us have been talking about these themes for a long time. In my own small way, I have written a number of articles and blogposts about eGovernment and Joined-Up Government, and I submitted something on Shared Services to the Cabinet Office in January 2006, most of which is probably still valid. See previous posts on this blog – eGovernment, Joined-Up, Shared Services.

Philip Boxer, Creating Value in Ecosystems (December 2010)

Jerry Fishenden and Mark Thompson, Digital Government, Open Architecture, and Innovation: Why Public Sector IT Will Never Be the Same Again (Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory September 2012)

Mike Martin, Open Architecture Critique – A Draft (March 2014)

David Sprott and Richard Veryard, Shared Services for the UK Public Sector (Submission to the Cabinet Office, CBDI Forum January 2006)

Richard Veryard, Joined-Up Services (Review of the Public Management and Policy Association. February 2002)

Richard Veryard and Philip Boxer, Public Sector IT – The CSA Case (December 2004)

See also David Sprott’s response to this post. Open Architecture for the Public Sector (May 2014)

Frank is Director of Strategic Planning at an insurance company and he is very stressed. The company has had significant challenges recently with implementing strategic initiatives effectively and the C-suite has set an aggressive customer service transformation target. Frank knows he is on the hook for a robust implementation plan that will span multiple service

The post Is the Business Model Canvas a useful tool in an Enterprise Architect’s toolbox? appeared first on Louise A Harris on Enterprise Business Architecture.

One of the most challenging aspects in our role as architects is that we often have to influence without direct authority. We often wrestle with this fact as we may not have the managerial clout and there may be lack of clarity on what precisely we are accountable for. Perhaps simply stated, we have to be THE accountable party for…

|

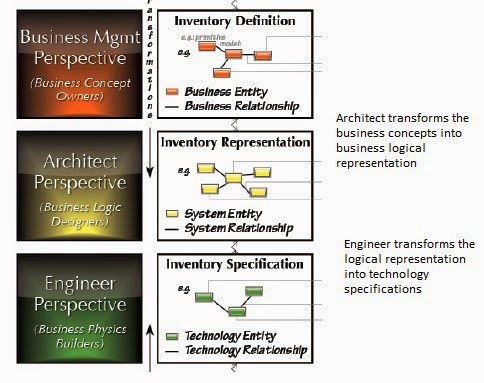

| Architect and Engineer Perspectives – in Zachman Framework All Copyrights with Zachman International |

TOGAF though defines Architect roles well; it probably does not clearly differentiate between an Architect and an Engineer at a role profile level. But it does offer a good methodical (as you can expect from TOGAF) and well defined classification of view; namely, Business Architecture View, Data Architecture View, Software Engineering View, System Engineering View and so on. In my opinion that works well too as with these views an organisation can then map roles, responsibilities of Architects and Engineers onto its operating model.

While many readers of this blog may or may not agree with precise definitions, I think this is still a good enough framework for us to start building operating model constructs around how best do Architects work with Engineers? Or vice versa! In some organisation they may be played by single role profile, in large environments it may be spread across say two or three role profiles. In an outsourced environment, Architect role may still be part of the retained IT staff and Engineers (or Engineering Services) may be procured from suppliers. I suppose, individual organisational operating model will dictate the specifics on these.