Redefining traceability in Enterprise Architecture and implementing the concept with TOGAF 9.1 and/or ArchiMate 2.0

One of the responsibilities of an Enterprise Architect is to provide complete traceability from requirements analysis and design artefacts, through to implementation and deployment.

Along the years, I have found out that the term traceability is not always really considered in the same way by different Enterprise Architects.

Let’s start with a definition of traceability. Traceable is an adjective; capable of being traced. Trying to find a definition even from a dictionary is a challenge and the most relevant one I found on Wikipedia which may be used as a reference could be “The formal definition of traceability is the ability to chronologically interrelate uniquely identifiable entities in a way that is verifiable.”

In Enterprise Architecture, traceability may mean different things to different people.

Some people refer to

· Enterprise traceability which proves alignment to business goals

· End-to-end traceability to business requirements and processes

· A traceability matrix, the mapping of systems back to capabilities or of system functions back to operational activities

· Requirements traceability which assists in quality solutions that meets the business needs

· Traceability between requirements and TOGAF artifacts

· Traceability across artifacts

· Traceability of services to business processes and architecture

· Traceability from application to business function to data entity

· Traceability between a technical component and a business goal

· Traceability of security-related architecture decisions

· Traceability of IT costs

· Traceability to tests scripts

· Traceability between artifacts from business and IT strategy to solution development and delivery

· Traceability from the initial design phase through to deployment

· And probably more

The TOGAF 9.1 specification rarely refers to traceability and the only sections where the concept is used are in the various architecture domains where we should document a requirements traceability report or traceability from application to business function to data entity.

The most relevant section is probably where in the classes of architecture engagement it says:

“Using the traceability between IT and business inherent in enterprise architecture, it is possible to evaluate the IT portfolio against operational performance data and business needs (e.g., cost, functionality, availability, responsiveness) to determine areas where misalignment is occurring and change needs to take place.”

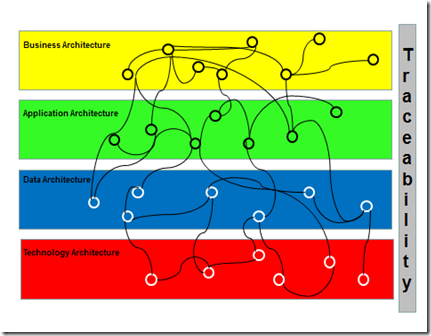

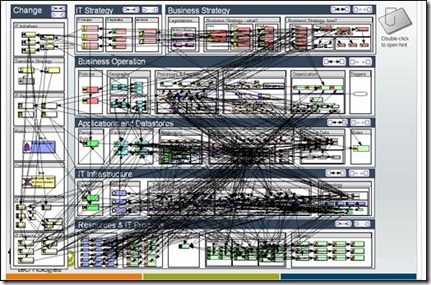

And how do we define and document Traceability from an end user or stakeholder perspective? The best approach would probably to use a tool which would render a view like in this diagram:

In this diagram, we show the relationships between the components from the four architecture domains. Changing one of the components would allow doing an impact analysis.

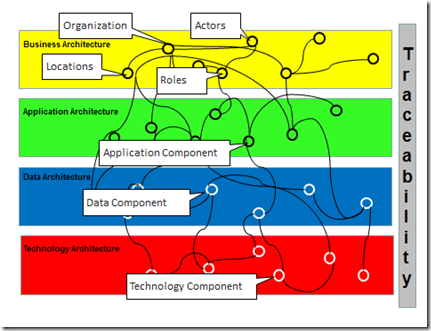

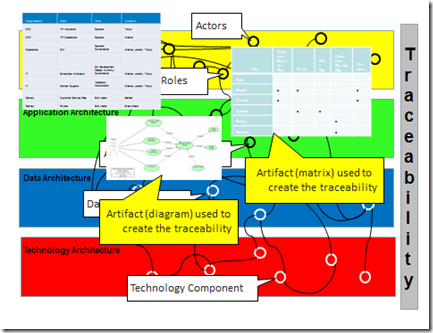

Components may have different meanings as illustrated in the next diagram:

Using the TOGAF 9.1 framework, we would use concepts of the Metamodel. The core metamodel entities show the purpose of each entity and the key relationships that support architectural traceability as stipulated in the section 34.2.1 Core Content Metamodel Concepts.

So now, how do we build that traceability? This is going to happen along the various ADM cycles that an enterprise will support. It is going to be quite a long process depending on the complexity, the size and the various locations where the business operates.

There may be five different ways to build that traceability:

· Manually using an office product

· With an enterprise architecture tool not linked to the TOGAF 9.1 framework

· With an enterprise architecture tool using the TOGAF 9.1 artifacts

· With an enterprise architecture tool using ArchiMate 2.0

· Replicating the content of an Enterprise Repository such as a CMDB in an Architecture repository

1. Manually using an office product

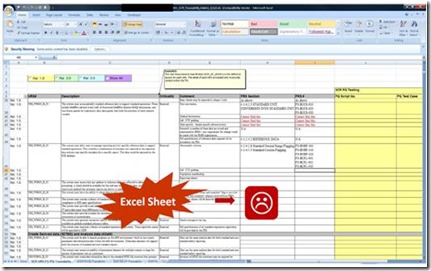

You will probably document your architecture with the use of word processing, spread sheets and diagramming tools and store these documents in a file structure on a file server, ideally using some form of content management system.

Individually these tools are great but collectively they fall short in forming a cohesive picture of the requirements and constraints of a system or an enterprise. The links between these deliverables soon becomes non manageable and in the long term impact analysis of any change will become quite impossible. Information will be hard to find and to trace from requirements all the way back to the business goal that drives it. This is particularly difficult to achieve when requirements are stored in spread sheets and use cases and business goals are contained in separate documents. Other issues such as maintenance and consistency would have to be considered.

2. With an enterprise architecture tool not linked to the TOGAF 9.1 framework

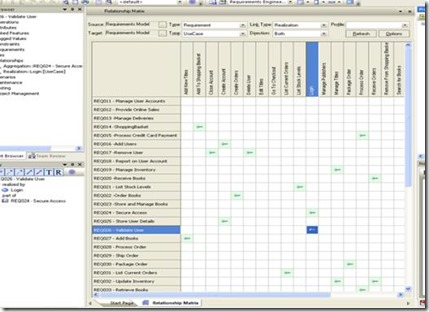

Many enterprise architecture tools or suites provide different techniques to support traceability but do not really describe how things work and focus mainly on describing requirements traceability. In the following example, we use a traceability matrix between user requirements and functional specifications, use cases, components, software artifacts, test cases, business processes, design specifications and more.

Mapping the requirements to use cases and other information can be very labor-intensive.

Some tools also allow for the creation of relationships between the various layers using grids or allowing the user to create the relationships by dragging lines between elements.

Below is an example of what traceability would look like in an enterprise architecture tool after some time. That enterprise architecture ensures appropriate traceability from business architecture to the other allied architectures.

3. With an enterprise architecture tool using the TOGAF 9.1 artifacts

The TOGAF 9.1 core metamodel provides a minimum set of architectural content to support traceability across artifacts. Usually we use catalogs, matrices and diagrams to build traceability independently of dragging lines between elements (except possibly for the diagrams). Using catalogs and matrices are activities which may be assigned to various stakeholders in the organisation and theoretically can sometimes hide the complexity associated with an enterprise architecture tool.

Using artifacts creates traceability. As an example coming from the specification; “A Business Footprint diagram provides a clear traceability between a technical component and the business goal that it satisfies, while also demonstrating ownership of the services identified”. There are other artifacts which also describe other traceability: Data Migration Diagram and Networked Computing/Hardware Diagram.

4. With an enterprise architecture tool using ArchiMate 2.0

Another possibility could be the use of the ArchiMate standard from The Open Group. Some of the that traceability could also be achievable in some way using BPMN and UML for specific domains such as process details in Business Architecture or building the bridge between Enterprise Architecture and Software architecture.

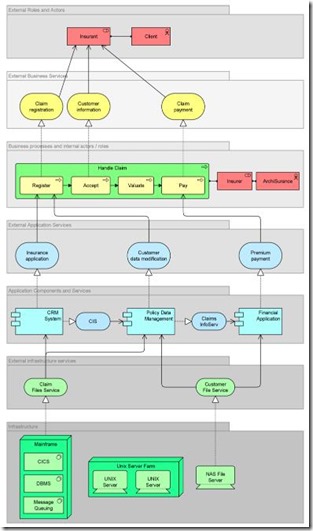

With ArchiMate 2.0 we can define the end to end traceability and produce several viewpoints such as the Layered Viewpoint which shows several layers and aspects of an enterprise architecture in a single diagram. Elements are modelled in five different layers when displaying the enterprise architecture; these are then linked with each other using relationships. We differentiate between the following layers and extensions:

· Business layer

· Application layer

· Technology layer

· Motivation extension

· Implementation and migration extension

The example from the specification below documents the various architecture layers.

As you will notice, this ArchiMate 2.0 viewpoint looks quite similar to the TOGAF 9.1 Business Footprint Diagram which provides a clear traceability between a technical component and the business goal that it satisfies, while also demonstrating ownership of the services identified.

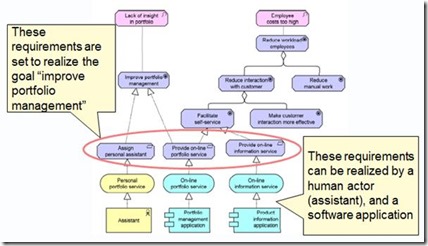

Another example could be the description of the traceability among business goals, technical capabilities, business benefits and metrics. The key point about the motivation extension is to work with the requirement object.

Using the motivation viewpoint from the specification as a reference (motivation extension), you could define business benefits / expectations within the business goal object, and then define sub-goals as KPIs to measure the benefits of the plan and list all of the identified requirements of the project / program. Finally, you could link these requirements with either application or infrastructure service object representing software or technical capabilities. (Partial example below).

One of the common questions I have recently received from various enterprise architects is “Now that I know TOGAF and ArchiMate… how should I model my enterprise? Should I use the TOGAF 9.1 artifacts to create that traceability? Should I use ArchiMate 2.0? Should I use both? Should I forget the artifacts…”. These are good questions and I’m afraid that there is not a single answer.

What I know is that if I select an enterprise architecture tool supporting both TOGAF 9.1 and ArchiMate 2.0, I would like to be able to be able to have a full synchronization. If I model a few ArchiMate models I would like my TOGAF 9.1 artifacts to be created at the same time (catalogs and matrices) and if I create artifacts from the taxonomy, I would like my ArchiMate models also to be created.

Unfortunately I do not know the current level of tools maturity and whether tools vendors provide that synchronization. This would obviously require some investigation and should be one of the key criteria if you were currently looking for a product supporting both standards.

5. Replicating the content of an Enterprise Repository such as a CMDB in an Architecture repository

This other possibility requires that you have an up to date Configuration Management Database and that you developed an interface with your Architecture Repository, your enterprise architecture tool. If you are able to replicate the relationships between the infrastructure components and applications (CIs) into your enterprise architecture tool that would partially create your traceability.

If I summarise the various choices to build that enterprise architecture traceability, I potentially have three main possibilities:

Achieving traceability within an Enterprise Architecture is key because the architecture needs to be understood by all participants and not just by technical people. It helps to incorporate the enterprise architecture efforts into the rest of the organization and it takes it to the board room (or at least the CIO’s office) where it belongs.

· Describe your traceability from your Enterprise Architecture to the system development and project documentation.

· Review that traceability periodically, making sure that it is up to date, and produce analytics out of it.

If a development team is looking for a tool that can help them document, and provide end to end traceability throughout the life cycle EA is the way to go Make sure you use the right standard and platform. Finally, communicate and present to your stakeholders the results of your effort.