A couple of days ago a tweet from John Gøtze cought my attention

EA can be agile and scrummilicious, says @soerenstaun in guest lecture at the IT University of Copenhagen.

— John Gøtze (@gotze) 29. April 2013

And my reaction to it was it should:

“@gotze: EA can be agile and scrummilicious, says @soerenstaun in guest lecture at the IT University of Copenhagen.” I say it should!

— Kai Schlüter (@ChBrain) 29. April 2013

|

| (c) Tom Graves |

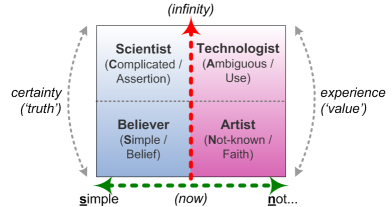

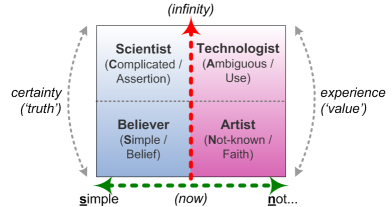

To explore this a bit further now finally this blog post. When I am tasked to implement Enterprise Architecture first time or to improve an existing capability then I put an agile approach in the core, preferable SCRUM. There is various reasons for this. To explain the concept I borrow the SCAN framework from Tom Graves, here in particular the post Sensemaking – modes and disciplines.

In my implementations of Enterprise Architecture activities I focus on the problem space Ambiguous and Not-Known. Ambiguous problems can be quite well solved with SCRUM, where “the whole is greater than the sum of it parts”, Aristotle. Agile approaches which do not put the team into the centre of their methodology do not seem to work as well in this problemspace. The identification to which quadrant a problem and the corresponding solution belongs is in my mind always an ambiguous problem, due to the scope of Enterprise Architecture, trying to cover the whole [which is more than the sum of its parts].

Problems which belong to Simple or Complicated I usually hand over as fast as possible to better suited teams or individuals, while the ambiguous problems I keep inside of Enterprise Architecture. The Not-Known space is total different and typically I focus on finding the Innovation which emerges here instead of trying to force it. I believe that Innovation can be easier found peripheral and not really by looking for it centrally.

By implementing SCRUM in the center some key elements needs to be in place to succeed. One of the most crucial elements is the Chief Architect, be it the official announced Chief Architect, or a manager (e.g. CIO) who is filling that role. The Chief Architect is the one who gets the SCRUM role Product Owner assigned. And here typically some effort and attention is needed to secure that the Chief Architect is focussing on delivering into his role as Product Owner instead of doing the actual work. The work should be done by the SCRUM team (or Pigs).

The most important element here is to create an environment in which the team utilizes the strenghts of each other. And here also lies one of the biggest challenges, because most Enterprise Architects have been grown from technical roles and have been survived quite some selection criterias till they have become an Enterprise Architect. Statistically I observe a high amount of heroes or divas, who are quite biased that an Enterprise Architect and especially they themselves are the crown of the evolution. Concepts like the Peter Principle support that thinking even more. 🙂

The only role which is fairly easy to fill is the SCRUM Master. Just take any good SCRUM Master who is NOT knowing much about Enterprise Architecture (preferred) or willingly not going into the content (sometimes hard, if the SCRUM Master is self biased believing to know better about Enterprise Architecture). So literally someone who only focusses on securing that the process runs.

This is of course not always easy to implement, but it is my main target to achieve. And I continue developing a team towards that target, till it is achieved. And when achieved the speed can be even increased, because then the environmental problems are solved and the focus can be on the delivery of good Enterprise Architecture Services, which is a post I also plan. SCRUM helps me to deliver to my main objective. Enterprise Architecture and especially my approach GLUE is about People first:

Comments as always more than welcome.

![]()