Until quite recently, IT security was the exclusive domain of security specialists. However, in the last couple of years, organizations have started to realize that IT-related risks cannot be seen in isolation, and should be considered as an integral part of Enterprise Risk and Security Management (ERSM). ERSM includes methods and techniques used by organizations to manage all types of risks related to the achievements of their objectives.

It is only natural to place ERSM in the context of Enterprise Architecture (EA), which provides a holistic view on the structure and design of the organization. Therefore, it is not surprising that EA methods such as TOGAF include chapters on risk and security (although the integration of these topics in the overall approach is still open for improvement), and a security framework such as SABSA shows a remarkable similarity to the Zachman framework for EA. And as a corollary, it also makes perfect sense to use the ArchiMate language to model risk and security aspects.

The previous blog post in this series outlined a method for EA-based ERSM with ArchiMate. This article proposes an initial mapping of risk and security concepts to ArchiMate concepts, and illustrates how these concepts can be used as a basis for performing an organization-wide risk assessment.

ArchiMate mapping of risk concepts

Most of the concepts used in ERSM standards and frameworks can easily be mapped to existing ArchiMate concepts. And since ERSM is concerned with risks related to the achievement of business objectives, these are primarily concepts from the motivation extension.

-

Any core element represented in the architecture can be an asset, i.e., something of value susceptible to loss that the organization wants to protect. These assets may have vulnerabilities, which may make them the target of attack or accidental loss.

-

A threat may result in threat events, targeting the vulnerabilities of assets, and may have an associated threat agent, i.e., an actor or component that (intentionally or unintentionally) causes the threat. Depending on the threat capability and vulnerability, the occurrence of a threat event may or may not lead to a loss event.

-

Risk is a (qualitative or quantitative) assessment of probable loss, in terms of the loss event frequency and the probable loss magnitude (informally, ‘likelihood times impact’).

-

Based on the outcome of a risk assessment, we may decide to either accept the risk, or set control objectives (i.e., high-level security requirements) to mitigate the risk, leading to requirements for control measures. The selection of control measures may be guided by predefined security principles. These control measures are realized by any set of core elements, such as business process (e.g., a risk management process), application services (e.g., an authentication service) or nodes (e.g., a firewall).

ArchiMate mapping of risk concepts

Using one of the extension mechanisms as described in the ArchiMate standard, risk-related attributes can be assigned to these concepts. The Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR) taxonomy, adopted by The Open Group, provides a good starting point for this.

Qualitative risk assessment

If sufficiently accurate estimates of the input values are available, quantitative risk analysis provides the most reliable basis for risk-based decision making. However, in practice, these estimates are often difficult to obtain. Therefore, FAIR proposes a risk assessment based on qualitative (ordinal) measures, e.g., threat capability ranging from ‘very low’ to ‘very high’, and risk ranging from ‘low’ to ‘critical’. The following picture shows how these values can be linked to elements in an ArchiMate model, and how they can be visualized in ‘heat maps’:

-

The level of vulnerability (Vuln) depends on the threat capability (TCap) and the control strength (CS). Applying control measures with a high control strength reduces the vulnerability level.

-

The loss event frequency (LEF) depends on both the threat event frequency (TEF) and the level of vulnerability. A higher vulnerability increases the probability that a threat event will trigger a loss event.

-

The level of risk is determined by the loss event frequency and the probable loss magnitude (PLM).

Qualitative risk assessment

The example below shows a simple application of such an assessment. A vulnerability scan of the payment system of an insurance company has shown that the encryption level of transmitted payment data is low (e.g., due to an outdated version of the used encryption protocol). This enables a man-in-the-middle attack, in which an attacker may modify the data to make unauthorized payments, e.g., by changing the receiving bank account. For a hacker with medium skills (medium threat capability) and no additional control measures, this leads to a very high vulnerability (according to the vulnerability matrix above). Assuming a low threat event frequency (e.g., on average one attempted attack per month), according to the loss event frequency matrix, the expected loss event frequency is also low. Finally, assuming a high probable loss magnitude, the resulting level of risk is high. As a preventive measure, a stronger encryption protocol may be applied. By modifying the parameters, it can be shown that increasing the control strength to ‘high’ or ‘very high’, the residual risk can be reduced to medium. Further reduction of this risk would require other measures, e.g., measures to limit the probable loss magnitude.

Risk analysis example

By linking risk-related properties to ArchiMate concepts, risk analysis can be automated with the help of a modeling tool. In this way, it becomes easy to analyze the impact of changes in these values throughout the organization, as well as the effect of potential control measures to mitigate the risks. For example, the business impact of risks caused by vulnerabilities in IT systems or infrastructure can be visualized in a way that optimally supports security decisions made by managers.

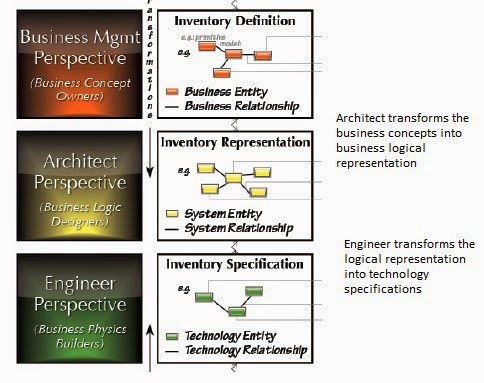

Enterprise Architecture (EA) has changed exponentially over the years with transforming from an IT-driven initiative to a business strategy necessity. EA as a field formally took shape in 1987 with the publication of John Zachman’s article

Enterprise Architecture (EA) has changed exponentially over the years with transforming from an IT-driven initiative to a business strategy necessity. EA as a field formally took shape in 1987 with the publication of John Zachman’s article