Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2013/11/07/saving-ea-from-itself-1-intro/

What’s wrong with enterprise-architecture? For that matter, what’s right with it? How can we do more of what’s right and less of what’s wrong? And what is the point of EA, anyway?

Following on from those posts on certification and EA, I want to do another brief series, way up at the big-picture level again, addressing the simple question of Why EA? In short, what’s it for? And once we’re clear on what it’s for, how well are we doing what’s for? How could we do it better?

What’s driving me, here, is a paraphrase of Russ Ackoff:

Doing the wrong thing better merely makes things worse

What worries me is that much of the current supposed ‘success’ in EA is actually just that: doing the wrong thing better. (And yes, sorry, but once again I am going to have to single out the TOGAF / Archimate axis here as a prime example of ‘doing the wrong thing’… or, more accurately, doing a different ‘right thing’ but making it lethally-wrong and lethally-dangerous by calling it something else that it isn’t.) Collectively, the better we get at doing the wrong thing, the more we’re making things worse – and yet we seem to have almost no way to see that we’re making things worse. Collectively, we’re so much blinded by our own so-called ‘success’ at the small-picture level that we’re failing to see that we’re at present setting ourselves up for a really primal failure at the big-picture scale. That’s the problem; that’s the tragedy here.

Seems to me that there’s an urgent need to save enterprise-architecture’ from its own mistaken ‘success’ – or, in short, saving enterprise-architecture from itself.

What I’ll do in this brief five-part series is as follows:

- Part 1: Introduction: this post, setting the overall scene, about the basic need for an ‘architecture of the enterprise’

- Part 2: Personal background: a bit about my own working-background, to explain why I interpret EA in the way that I do

- Part 3: Sally’s comment: exploring a comment by Sally Bean on a previous post here, to see what’s missing from current EA

- Part 4: Len’s comment: exploring a comment by Len Fehskens on the same post, to see how and why EA goes wrong

- Part 5: What next?: given the gap between what EA should be doing, versus what it’s doing now, what can we do to correct our course?

But first, what’s the point of this, anyway? – this overall discipline of enterprise-architecture? For this, I’d suggest the following principles and ground-rules:

– ‘Enterprise architecture’ consists of two words – ‘enterprise‘, and ‘architecture‘ – in conjunction with each other. We clarity not only on each of those terms, but how they fit together.

– In essence, ‘enterprise‘ is just an idea, a desire, an intent, a vision, a promise – almost any of those terms will do. It’s a kind of ‘drive, with purpose’.

– Confusingly, the term ‘enterprise’ is also used for the practical expression of an enterprise in that sense above. In other words, not so much purpose on its own as, for example, an ‘ecosystem with purpose’ – a complex, adaptive, emergent ‘system’ with some form of implied or explicit collective-purpose.

– Even more confusingly, the term ‘enterprise’ is also often used for an organisation in context of an enterprise, in that sense above. In other words, a blurring-together of the ends represented by enterprise – the idea, the purpose, the drive – and a means (the organisation) through which some aspects of that enterprise can be achieved. Treating a means as an end in itself is rarely a good idea…

– In practice, every enterprise exists in context of, and often interacting with, many other enterprises.

– In essence, ‘architecture‘ is the practical expression of one very simple idea: things work better when they work together, on purpose.

– A core understanding of any real-world architecture, when viewed as a ‘system’, is that everything depends on everything else, and everything is in context of everything else.

– A direct corollary of this interdependency is that, for an an architecture, everything and nothing is ‘the centre’ of the architecture, all at the same time. The moment we make anything or any domain to be ‘the centre’ – with everything else always solely subservient or in context of that arbitrarily chosen ‘the centre’ – we set ourselves up for whole-of-system dysfunction or failure.

– In an architecture, all boundaries are ultimately artificial, arbitrary and potentially-problematic. (However, as in an ecosystem, boundaries are also where many of the most interesting things can happen…)

There’s plenty more we could add to those lists, but that’s probably enough to get started.

An enterprise-architecture brings all of these themes together, to combine together the story of the architecture with the structures of the architecture to do something that’s useful in practice.

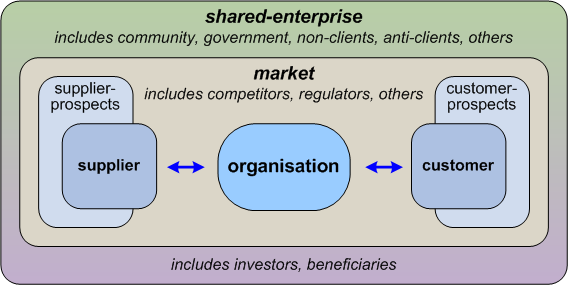

We’d typically develop an architecture for an organisation about the enterprise within which that organisation operates. In order to create an ‘enterprise-story’ that meaningfully describes the organisation’s stakeholders, we’d typically describe an enterprise that’s some three or more steps in scope larger than the scope of the respective organisation:

And we’d also need to support multiple views into, within and around the organisation and enterprise – inside-in, inside-out, outside-in and outside-out:

We can choose to view and act on only a subset of that overall context-space – but we must never forget that it is only a subset, not the whole – and also that the boundaries for that subset, and the subset itself, are a choice, not a ‘fact’.

A practical example

As usual, that’s almost certainly too abstract on its own, so we’ll need a concrete example – in this case, an airport.

An airport exists in context of the enterprise of air-travel (people) and air-freight (things), which in turn are subsets of the broader enterprises of travel and freight.

The airport can be said to exist as a set of physical structures – terminals, hangars, runways, sensors, control-systems and much, much more – at an identifiable physical location. There are also mobile structures or entities – vehicles, aircraft and suchlike – that can move around within and/or across the boundaries of this physical ‘the airport’.

The airport is a node of and for a very wide variety of information-types and information-flows. In a sense, the airport ‘is’ information – though that’s definitely not all that it is.

The airport is a nexus for another very wide variety of people and people-relationships – travellers, employees of the airport itself, and employees and staff of many other organisations that intersect with the airport, such as delivery-drivers, bus-drivers, government, police, health and many more.

The airport is also a nexus for stories – for individual and collective purpose. A vast array of enterprise-stories intersect with, traverse through and, in some cases, terminate at the airport. (This is part of what makes the question ‘Who is the customer of the airport?’ very definitely non-trivial.) Some of these stories are in relation to the airport, but not necessarily associated directly with the airport itself – for example, as a symbol of civic or national pride, or as a focus for anticlients‘ disaffection.

Linking information and purpose, as money or finance, the airport is also an intersection for a vast array of financial concerns – the airport itself as a business, the airport as a place of business, the airport as a node in other businesses, the airport as both a source and sink for tax-revenue, and so on.

Aircraft fly in and out of the airport, in accordance with guidance from air-traffic control – which, by definition, operates at a larger scope than the airport itself. Much the same applies to land-vehicles moving in and out of the airport, although the guidance for that traffic is often more loosely controlled.

The airport has distinct zones (physical and otherwise), some of which require explicit management of boundaries – for example, the distinction between ‘air-side’ and ‘land-side’ within the airport terminals and out on the tarmac, or the operational boundary – and some of which are intentionally much more porous – for example, non-travellers on ‘land-side’ accompanying departing or arriving passengers, up to the ‘air-side’ boundary. Much the same applies to information-flows: cell-phones and public over-the-air data-links can be used almost anywhere, but monetary information-flows and much of the air-traffic-management information will be tightly constrained.

Also – and too often forgotten – the fact of the airport as a large and largely-open physical location means that there are many potential or actual intersections with wildlife. Rodents and network-cables are not a good mix; neither are large animals or large birds with aircraft, on the land or in the air respectively; insect-infestations can cause other nightmare problems, such as cockroaches in kitchens, or wasp-nests high up in the ceiling of an airport-terminal building.

And then – just to make things even more fun – there are other crucial factors over which we have no control at all, but which we must include in our architecture design. For the airport, the most obvious example is weather. How will you manage high winds, heavy rain, fog, ice, snow, sleet? You can stop aircraft taking off, if you have to, but aircraft have to land somehow… Technology can help with that – ILS, for example, Instrument Landing System – but what about aircraft that aren’t equipped with that technology? If you have hazardous conditions, what’s the impact for different sizes and types of aircraft? – a little two-seater general-aviation or a microlight is just as much ‘air-traffic’ as a 500-seater commercial airliner. And then there are other human factors outside our control: would-be terrorists, of course – everyone worries about those. But you also might have a disgruntled nearby resident with an anti-aircraft gun (real example: Germany) or an idiot with a shotgun, sitting in a garden-chair held aloft by balloons wandering into the airport flight-path (real example: also US) or a 40ft flying-pig balloon drifting loose on a calm day on the approach to the busiest airport in the world (thank you, Pink Floyd). Oh, and your everyday teenage idiot who thinks it’s fun to shine his $5 laser onto an airliner on final approach. (Yeah, I’ve personally been on the receiving end of that last one – literally blinding for a few seconds. So think about what it’s like for the flight-crew, in the last few seconds of finals – and what it could mean for the airport…)

All of this is within the scope of an overall enterprise-architecture for the airport: everything depends on everything else. And anyone working on any given subset of that architecture still needs always to be aware of that whole scope, and aware of the potential for interactions from elements conventionally described as ‘out-of-scope’ for their own selected sub-domain – otherwise there is significant risk of creating conditions for ‘unexpected’ failure.

Arbitrarily selecting one sub-domain within this overall context-space – information-systems and information-flows, for example – and myopically ignoring all other aspects of the enterprise, will cause failure within the overall enterprise. (That’s classic IT-centric ‘enterprise’-architecture in a nutshell…)

Arbitrarily privileging one sub-domain over all others within the shared-enterprise will cause dysfunctions, sometimes up to the level of total failure. Consider, for example, how ‘security’, in many different forms and senses, now forms a literal blockade in both directions on the boundaries between ‘air-side’ and ‘land-side’ – and, amongst other ‘unintended consequences’, often imposes huge delays onto the flows of passenger-traffic.

Arbitrarily privileging the interests of specific stakeholders over above those of others can cause not only flow-dysfunctions – as for ‘security’ above – but also can skew the entire design and operation of the airport such that other stakeholders can become deeply disaffected, and risk becoming active anticlients for the airport. For example, contrast London City Airport – where the whole focus is on passenger through-flow, and ‘check-in to departure’ time will often be a half-hour or less – with a large commercial airport such as London Heathrow or London Stansted – where the airport-terminal is in essence set up as a giant, mandatory, over-priced shopping-mall, and where the official ‘check-in to departure’ time is listed as three hours or more.

Yes, there’s a lot in there. (Ask Norman Foster, who designed the terminal-buildings for Stansted and Heathrow Terminal 5: but even he only did the architecture for the terminals, not the entire airport!) And yes, an enterprise-architect for the airport would need to be aware of all of that. Not necessarily design for it all – in fact it’s unlikely that any one person could design for it all. But be aware of it at all times, and take it into account at all times, a definite yes.

That’s enterprise-architecture.

By definition, that’s the necessary scope and nature of an enterprise-architecture – because it’s the literal architecture of the overall enterprise.

Anything less is not enterprise-architecture: it’s an arbitrary sub-domain pretending to be the whole, or deluding itself that it ‘is’ the whole – with potentially-disastrous consequences for the real enterprise-as-whole.

Describing as ‘enterprise-architecture’ something that is not the literal ‘architecture’ of the enterprise can be very dangerous indeed – in many, many different senses. For example, if anything goes wrong – if anything ‘unexpected’ happens – we won’t be able to understand why, or what to do about it, because we’d have arbitrarily dismissed as ‘out of scope’ everything that we’d actually need to know there. By definition, it’s the wrong thing to do, the wrong way to approach enterprise-architecture.

And yet that is exactly what is done within many current approaches to ‘enterprise’-architecture: they assert and insist that one subset ‘is’ the whole, and either myopically, or by deliberate intent, ignore all the rest. Yes, collectively we seem to be getting much better at doing what’s claimed to be ‘enterprise’-architecture: but it’s the wrong way to do it, we now know that it’s the wrong way to do it, and doing the wrong thing better merely makes things worse.

If our putative profession keeps on going much further in the direction that it’s headed now, the inevitable failures, at ever larger and larger scales, will bring the entire discipline of enterprise-architecture into such disrepute that it will, of necessity, die. And that won’t be a good outcome for anyone. Not for anyone at all.

That’s the real concern that’s at risk here.

And we’ll explore that more in the later parts of this series.

Over to you for any comments so far?

[Update (11Nov13) – I don’t like changing content once something’s published, but in this case I really did need to add, in the ‘airport’ example, the section on weather and other factors that are inherently ‘outside our control’.]