Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2013/12/03/can-complex-systems-be-architected/

A great question from Jeff Sussna, as a follow-on to my ‘manifesto‘ post:

- RT @jeffsussna: @tetradian question: can complex systems like your ‘enterprise’ actually be ‘architected’?

And yeah, it’s also a tricky question, because a lot of any answer depends on what’s meant by ‘complex systems’, ‘enterprise’ and ‘architected’…

In terms of what’s commonly meant by each of those terms, and what most commonly claims to be ‘enterprise’-architecture, the short-answer is ‘Probably no‘. What you’d end up with, at best, is something a bit like an odd mixture of random hype and rigid Taylorism – where endless attempts are made to force-fit not just the organisation, but everything that it touches, into line with the latest technology-laden fad. True, that kind of mess might even hold together for a short while, in some cases; but its internal contradictions will cripple it at best, and would more usually lead to catastrophic collapse, more likely sooner than later.

Yet to me, though, using the definitions and techniques that I do, the short-answer to Jeff’s question would be ‘Probably yes‘ – it can. The somewhat-longer-answer is that it’s definitely a qualified ’Yes’, with an awful lot of ‘It depends‘ and suchlike… which is where the choices for those definitions and techniques really start to matter…

The first part of the ‘It depends’ in Jeff’s question relates to what’s meant by ‘complex systems‘. To some people – perhaps especially in the IT-related trades – ‘complexity’ is just a more extreme version of ‘complicated’: a quantitative difference, “complicated that we haven’t as yet quite pinned down the rules and algorithms for”. To me, though, I’d agree with those who argue that there’s a qualitative difference between ‘complicated’ and ‘complex’: for example, the kind of complexities that we see in wicked-problems, where even the act of looking at a context can itself change the context.

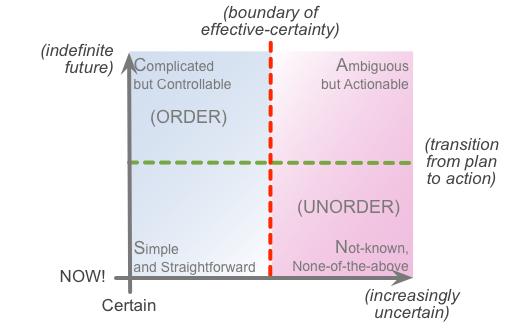

To use the SCAN diagram, the ‘complexity that’s just very complicated’ sits over on the left-side of the frame; inherent-ambiguity and other forms of ‘wicked-complexity’ sit more over to the right. That qualitative-difference between ‘very-complicated’ and ‘real-complexity’ in effect occurs at the point indicated by the red-line ‘boundary of effective-certainty’:

That boundary does sort-of move dynamically, and hence can give the illusion that it should be possible to push the boundary indefinitely to the right. In practice, though, there are real limits as to how far to the right ‘the complicated’ can go – for example, even just in a physics sense it’s limited by non-negotiable constraints such as the speed of light.

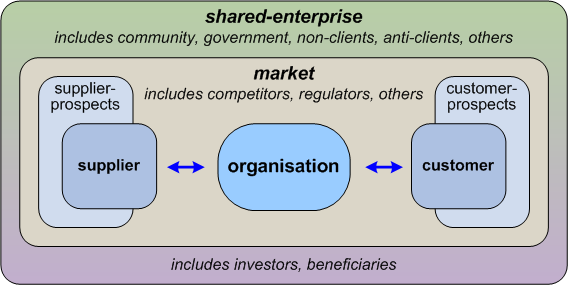

The second part of the ‘It depends’ in Jeff’s question relates to what’s meant by ‘enterprise‘. For this, I’d first point to one of the themes from the ‘manifesto’: that we create an architecture for an organisation, about its enterprise. In essence, ‘the organisation’ is what we want to architect – which, remember, includes both ‘order’ and ‘unorder’ – whereas ‘the enterprise’ is the effective outer-limit of the context for that ‘the organisation’.

It’s often useful to split the ‘not-the-organisation’ aspects of this ‘the enterprise‘ into two parts – ‘the market’, emphasising direct-transactions, and ‘the shared-enterprise’, more emphasising indirect-interactions – but that’s just a convenience, not a requirement. Anyway, here’s a visual summary of how I view ‘the enterprise’ in relation to ‘the organisation’:

To link this to the common ‘three architectures’ structure popularised in TOGAF and other mainstream ‘enterprise’-architecture frameworks:

- ‘organisation’: IT-Infrastructure Architecture / Technology Architecture

- ‘market’: Information-Systems Architecture (Data Architecture plus Applications Architecture)

- ‘shared-enterprise’: Business Architecture

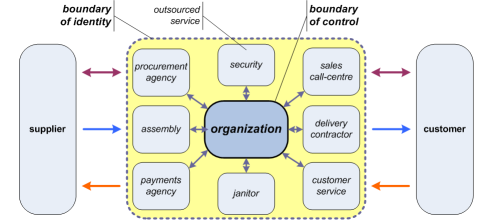

Crucially, anything beyond ‘the organisation’ is also, by definition, beyond our ‘control’. This can get especially complex where outsourced services are ‘inside’ the organisation’s boundary-of-identity – what others see as the effective boundary of ‘the organisation’ – but ‘outside’ the organisation’s own explicit boundary-of-control:

Within a well-constructed architecture, we do have plenty of options to influence the broader-shared enterprise – the ‘everything’ that’s beyond the organisation’s own boundary-of-control. But the notion that the organisation could simply demand that things happen, and they will, is definitely a delusion there (and even within the organisation itself, of course). In that sense, relations between ‘the organisation’ and ‘the enterprise’ will always be somewhat complex, somewhat emergent, even somewhat chaotic at times – and the architecture must be able to support that fact.

Hence the third part of the ‘It depends’ in Jeff’s question relates to what’s meant by ‘architected‘. One place we could usefully start would be the definition of ‘architecture’ used in the IEEE1471 and ISO42010 standards:

⟨system⟩ fundamental concepts or properties of a system in its environment embodied in its elements, relationships, and in the principles of its design and evolution

Sure, it’s a very structure-oriented view of architecture – there’s no reference to the narrative or story-aspects of architecture – and we have to hunt deeper into the standard to find other essentials such as the place of people in general. Even so, it’s probably usable enough for our purposes here.

Remember what I said earlier above that every real-world context will include elements ‘in’ all of the SCAN domains, and that, in turn, any architecture that relates to that context must be able to address all of those elements. So perhaps the simplest way to summarise what the ‘It depends’ here most depends on, is to use the categorisation of techniques and methods from the version of the SCAN diagram that I used in the ‘manifesto’:

That mapping gives us two keywords for typical assessment-techniques (‘rotation’ etc), and one keyword for typical decision-support deliverables (‘rules’ etc), for each of the SCAN domains:

– Simple (rules)

- regulation – reliance on rules and standards

- rotation – systematically switch between different elements in a predefined set, such as in a work-instruction or checklist (or in the elements in a framework such as SCAN itself)

– Complicated (algorithms)

- reciprocation – interactions should balance up, even if only across the whole

- resonance – systemic delays and feedback-loops may cause amplification or damping

– Ambiguous (patterns / guidelines)

- recursion – patterns may be ‘self-similar’ at every level of the context

- reflexion – intimations of the nature of the whole may be seen in any part of or view into that whole

– Not-known (principles)

- reframe – switch between nominally-incompatible views and overlays, to trigger ‘unexpected’ insights

- rich-randomness – use tactics from improv and suchlike to support ‘structured serendipity’

There are also a few other points that aren’t in that diagram, but are worth noting here. For example:

– We’d typically expect to do analysis in the Complicated domain (certainty-oriented, distant from the moment-of-action), versus experimentation in the Ambiguous domain: the former would expect to deliver a ‘knowable’ and repeatable result, whereas the latter quite probably would not.

– At the moment-of-action – where there’s no time to think, yet decisions do still have to be made – we’d expect a range of decision-support tools across the length of that horizontal-axis, ranging from step-by-step work-instructions over on the far left, to aircraft-industry-style action-checklists that bounce across the known / unknown boundary, to principles that can help keep decisions ‘on purpose’ even in the most extreme of uncertainty.

– Although it’s likely we would ultimately use all of these techniques and suchlike in every part of an architecture, we should expect to use ‘left-side’ techniques more often within the organisation, and ‘right-side’ techniques more often beyond the organisation, because the boundary of the organisation also represents its boundary-of-control, and hence the effective limits of its own certainty.

Remember also, from the ‘manifesto’, that all of the same concerns and principles apply to the architecture itself – including recursion, reframe, rich-randomness and so on.

Without this latter point about self-recursion and suchlike, then no, it’s probable that the architecture would not be able to work with, or even fully describe, any kind of complex-system.

Yet with this in place, and used appropriately, then yes, I’d suggest that we are able to architect any, and maybe even all, of the organisation’s structure, story and relationships with itself and the complex-systems within which it operates.

In other words, yes, we do need to accept and acknowledge that there’s a fair amount of ‘It depends’ involved here, as above: but given that, then yes, we can architect a complex-system – even as complex a system as a shared-enterprise.

I hope that adequately answers the question, perhaps?

Over to all of you to add your comments and suggestions, anyway.