Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2014/11/04/spot-the-difference/

“How do I loathe thee, TOGAF? Let me count the ways…”

In case anyone thinks that I’m just ‘TOGAF-bashing’ for the sake of it, I do believe that TOGAF has genuine value for what it was originally designed to do, namely architecture of enterprise-wide IT-infrastructure.

TOGAF 8.1 was actually pretty good at that, though by 2009 it was an urgent need of an update. Yet as I wrote back in February 2009, after the TOGAF 9 launch, to me TOGAF 9 represented a huge missed-opportunity, a disastrous hubris-laden wrong-turn. There were two choices: either stay with IT-architecture, and really develop the meta-architectures so as to make it self-updating to each change in technology (which was well within Open Group’s capabilities and remit); or go all-out to support a true ‘architecture of the enterprise’ (which, as an IT-standards body, Open Group was perhaps not well placed to do). In the end, they chose the worst of both worlds: a vaguely-revamped static framework that couldn’t keep pace with technological change, and that retained the inherently IT-centric ‘BDAT-stack’ yet also pretended that it would still work beyond IT (which, by definition, it can’t).

To be blunt, the current version of TOGAF looks like, and is, a classic example of a framework cobbled together out of disparate parts by a 200+ person committee. There are some excellent bits in it – my favourite is probably Bob Weisman’s work on capability-architectures – but overall it’s best described as a bloated, hugely-oversized, often-misleading, largely unusable mess. Even the ADM is a badly-reworked PDCA loop, with a misleadlingly-constrained ‘Act’ phase (ADM Phases B/C/D) and virtually no ‘Check’ phase (no ‘benefits-realisation’ or ‘lessons-learned’ in ADM Phases H/A).

Whilst TOGAF 8.1 was an IT-architecture framework that was good at what it did but needed some updating, TOGAF 9 and 9.1 are less-complete IT-architecture frameworks that are desperately pretending to be more than they are, and in practice are just-about usable only for the kind of now quite old big-IT that’s still in use only a specific subset of industries such as banking, insurance, finance and tax. There’s almost nothing in there that will help much, if at all, with mobile or social or internet-of-things or embedded health-technologies or ‘human apps’ such as Amazon’s ‘Mechanical Turk‘, or even key aspects of IT-disaster-recovery, because those are all contexts in which the human is deeply interwoven with the physical-machine is deeply-interwoven with the IT-technical is deeply interwoven with enterprise-purpose – whereas TOGAF and Archimate and the like only tackle the IT, leaving everything else as a supposedly all-but-irrelevant afterthought, a Somebody Else’s Problem.

The catch is that, as enterprise-architects, we are that ‘Somebody Else’: it’s our Problem. And we need real usable tools and frameworks to help us with that problem. Yet despite its vaunted claims to the contrary, TOGAF 9.1 is most definitely not one of them: it’s unsuited for the purpose, right down to the deepest roots of its internal architecture. But because it sits there like a dog-in-the-manger, hogging almost the entirety of that space, we’re stuck: none of us can move forward until we have some means to fix the resultant TOGAF-driven IT-centric mess.

Sigh…

To illustrate the point, let’s start with the centrepiece for TOGAF, the ADM (Architecture Development Method), and play a quick game of ‘Spot The Difference. Before we do that, let’s first have a quick check of the criteria for a framework that could actually work at a true whole-of-enterprise scope:

- It needs to be able to cover any scope and context, consistent yet self-adapting to all those different contexts.

- It needs to be able to work on any subsets of the overall scope, whilst still retaining full connection to that overall scope.

- It needs to be able to work with and develop for often-extreme uncertainty.

- It needs to support the full range from big-picture to detail-level, and from vision and strategy to implementation and operation.

- It needs to support continuous-learning and continuous improvement.

- In a business-sense, it needs to support real business-value.

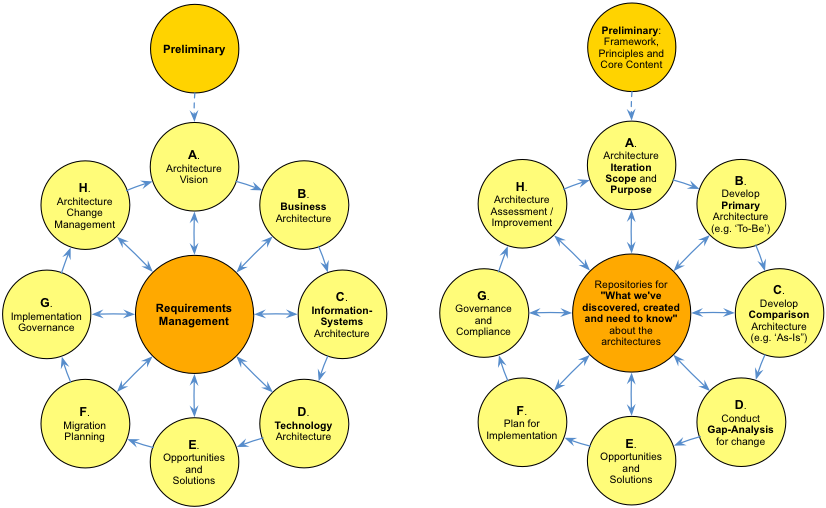

Given that list, let’s play Spot The Difference on the TOGAF ADM, versus an alternate methodology that follows what, on the surface, might seem to be the same structure:

(Click on the graphic to expand it, if need be.)

No doubt you’ve noticed all of the differences. But have you noticed why the differences exist, and what they imply in practice?

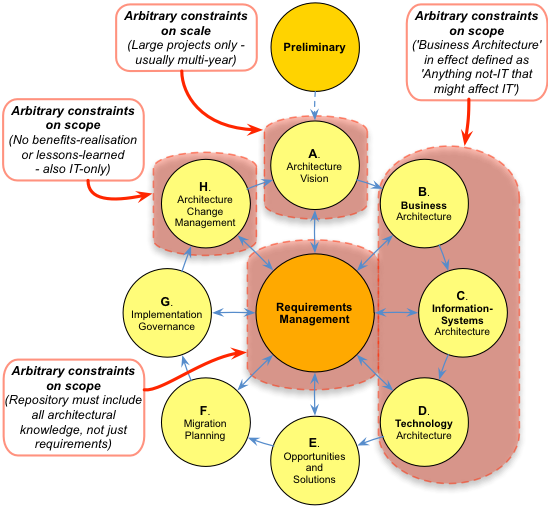

The graphic on the left side of that ‘Spot The Difference’ summarises a method – the standard TOGAF9 ADM. And as a method, it’s optimised for use in precisely one type of context – a specific form of IT-architecture – and in practice is too constrained to do almost anything else:

Implicit from the arrows on the graphic is that it is possible to use it in a non-linear way – though this is barely described in the documentation, with no actual instructions on how to do it.

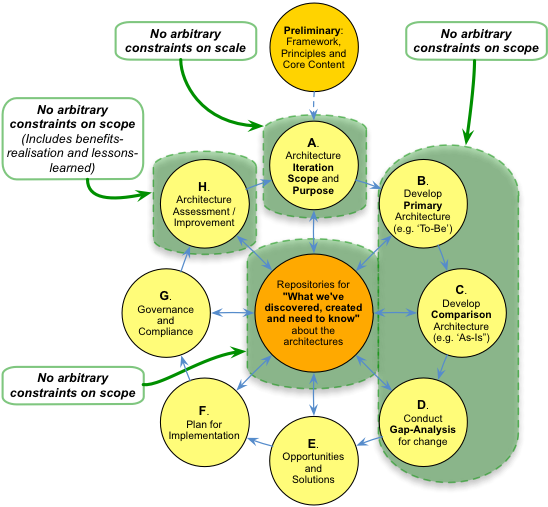

The graphic on the right side of that ‘Spot The Difference’ summarises a metamethod. And as a metamethod, it can be used either as-is, or in a self-adapting way to create context-specific methods for any type of scope and context – including (if with some twists) the TOGAF ADM itself:

(Note that it’s not that there’s no scope in Phases B, C and D, or that the scope is always an impossible ‘The Everything’ – but rather than the respective scope for the iteration is identified and defined in Phase A. That means that we can work on any scope, including subsets, supersets or intersecting-sets of the current scope, recursively, yet still do so in way that is clearly identifiable and appropriately-constrained for the current iteration.)

Implicit from the arrows on the graphic is that it can likewise be used in a non-linear way – but also fully-recursive, via the ‘any scope, any scale’ structure of Phases A to D.

(To be pedantic, that graphic on the right is itself an instance of a metametamethod for continuous-change and continuous-improvement. of which, for example, PDCA, OODA and the classic Tuckman ‘Group Dynamics’ project-cycle are other instances.)

Nothing much wrong with having a method like that of the ADM, that only works well with one type of scope and context, of course – as long as that scope and context are all it’d be used for.

The catch is that, courtesy of the hype-machine that is behind TOGAF these days, the graphic on the left is insistently marketed and ‘sold’ as if it’s the graphic on the right – as if the tiny subset of scope that the TOGAF ADM can cover is all that anyone would ever need in enterprise-architecture. Which it isn’t.

Which, since TOGAF can’t actually handle anything more than a very narrow type of scope – because that scope is hardwired right into its very structure – makes life very difficult indeed for those of us who do work at wider scopes and the rest of that list of criteria near the start of this post, and have to spend inordinate effort tidying up the TOGAF-created mess.

Bah.

But as enterprise-architects, that’s just the start of our TOGAF-created woes… Here are a few more:

– Pseudo-’non-proprietary’ versus real non-proprietary

Proprietary frameworks are bad news all round: that’s all that need be said on that.

Open Group do claim that TOGAF is ‘non-proprietary’. Yet I’d put quotes around that assertion, because calling TOGAF a ‘non-proprietary framework’ really is a stretch too far: it may be true that we might not have to pay to, uh, look at it, but that’s about it. ’Freemium’, just possibly: but the kind of ‘freemium’ that we can’t act do anything useful with unless we pony-up on the in-app purchases…

That’s because TOGAF itself is too incomplete to use ‘as-is’: there are key chunks missing, which means that it is, in effect, misleadingly useless, giving the impression of usability without actually providing it – kind of like a car that looks all shiny and new and ready to go but with key less-visible components like the drive-shaft and the steering-rods somehow just not there. In fact on its own, ‘out of the box’, the only people who could use TOGAF are those who already know enough real-world EA to be able to do without it – so the whole thing is all a bit moot anyway.

To make this ‘standard’ ‘non-proprietary’ framework usable in real-world practice, there’s a sizeable training-industry, all of it licensed at a fee to Open Group, and at serious cost to participants: back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests mid- to high tens of millions of dollars so far, and rising. And then there’s the ‘certification’: tested by multiple-choice exam – exactly how not to do skills-evaluation – and again a ‘nice little earner’, currently in the low tens of millions of dollars. ‘Non-proprietary’? Marketing hype-machine, yes, but ‘non-proprietary’ in any real sense of the word? – I think not…

True non-proprietary frameworks for EA do indeed exist: Kevin Smith’s PEAF and POET pairing is one that comes immediately to mind. Milan Guenther’s book ‘Intersection‘, on enterprise design, and Marlies Steenbergen and Martin Van Den Berg’s ‘Building An Enterprise Architecture Practice‘, on the DyA framework, are a lot more complete and usable than TOGAF, and also both come close to true non-proprietary, too: to get the full detail you’d have to buy the book, but that’s all.

To me the ideal would be some form of open-source architecture-framework – but it still doesn’t seem to be happening in any workable form as yet. Oh well.

– Enterprise-as-scope versus enterprise-as-domain

This is probably the single most misleading mistake in the whole of TOGAF, yet in some ways one of the hardest to see: conflating ‘enterprise’ as a scope, with ’enterprise’ as a domain in its own right.

In its Introduction, the TOGAF specification does define ‘enterprise’ in several ways: an organisation, a consortium of organisations, and so on. But what it doesn’t do is say – anywhere, as far as I can tell – that this is merely the scope of interest, to which all of the following specification would apply. It’s IT-architecture at an enterprise-wide scale, yes – but that’s not the same as ‘enterprise-architecture’, the literal ‘architecture of the enterprise’, where the enterprise itself is the domain of interest.

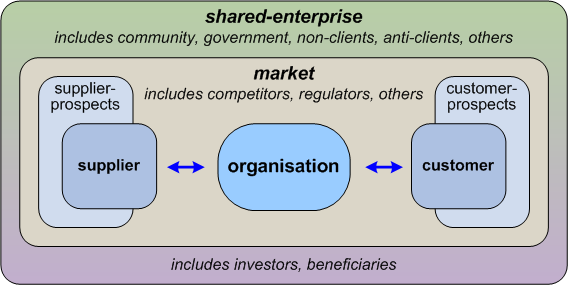

As described in the post ‘Organisation and enterprise‘, the scope we actually need to explore – the respective ‘enterprise’ – for any given architecture is at least two to three steps larger than the main scope of interest. At a whole-of-organisation level, for example, the respective ‘enterprise’ that we’d need to explore stretches way out beyond even the organisation’s business-market:

Yet TOGAF strongly implies, throughout the specification, that the organisation itself is ‘the enterprise’, the ultimate boundary of any architecture. As described in that ‘Organisation and enterprise’ post, this has serious consequences if we try to apply it at a business-architecture level, and often below that level as well.

That one double-error of conflation – perpetrated and perpetuated throughout the entire specification – leaves the framework wide-open to risk of perpetrating really serious term-hijacks, in which a tiny subset of a scope pretends to be the whole, blocking out the view of anything other than itself. Which is precisely what we see next, with the bewretched ‘BDAT-stack’…

– BDAT-stack versus real-world

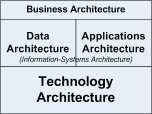

Like Archimate, which in essence follows the same pattern, TOGAF purports that the entirety of an enterprise-architecture can be split into exactly three sub-architectures:

- Business Architecture

- Information-Systems Architecture

- Technology Architecture

In TOGAF itself, Information-Systems Architecture may optionally be split into Data-Architecture and Applications-Architecture – hence the respective initials that give us that acronym ‘BDAT’, ‘Business, Data, Applications, Technology’.

Looking closer at the specification, it quickly becomes clear that each of these ‘architectures’ revolves entirely around what we might call ‘big-IT’ – the kind of systems run by an ‘IT Department’ of a large organisation of perhaps half a decade ago. It’s really obvious, for example, that the supposed ‘Business Architecture’ is barely about business at all, but could instead be summarised by the phrase ‘anything not-IT that might affect IT’.

The BDAT-stack is actually quite a good description of what’s needed for a big-IT infrastructure-architecture, where – in terms of that ‘enterprise’ model just above – ‘Information-Systems Architecture’ is the metaphoric equivalent of ‘suppliers and customers’, and ‘Business Architecture’ is the metaphoric equivalent of the ‘market’-space for that big-IT. But we need to realise that that ‘enterprise’-model won’t work upside-down: looking ‘up’ the stack is like looking upward from the bottom of a well, but looking ‘down’ the stack needs to take into account the whole context – of which the well itself is only one small part. Given that in most large-organisations their big-IT accounts for less than 10% of overall spend – and often a lot less than that – then it should be clear trying to claim as ‘enterprise-architecture’ an architectural model that can at best only describe perhaps one-tenth of the organisation’s concerns is somewhere between laughable and downright dangerous.

Let’s be blunt about this: the real world contains a lot more than just big-IT. Which means, also bluntly, that the ‘BDAT’ stack – fundamental to both TOGAF and Archimate, and the basis for Phases B, C and D in the TOGAF ADM – is misleadingly unusable for anything beyond IT-infrastructure architecture. Its descriptions even of Information-Systems Architecture, let alone Business-Architecture, are too incomplete and too misleading to be used for anything more than that.

– TOGAF metamodel versus real-world

There’s quite a nice metamodel in TOGAF 9, and nicely extended in TOGAF 9.1. It’s a very nice summary of the entities needed to describe a big-IT infrastructure and its business-context. But that is all that it can or should be used for: period. It’s usable solely for a very small subset of the enterprise: yet what we need – even for a real IT-architecture – must, by definition, be able to describe anything in that real-world enterprise. Which, unfortunately, the TOGAF metamodel actively prevents us from being able to do.

If you doubt this, try using the TOGAF metamodel to describe any whole-of-context business concern such as security or disaster-recovery, in which human activities and mechanical structures are necessarily ‘equal-citizens’ alongside the IT-based apps. Try using it to describe the relationships between information about a parcel, versus the parcel itself, in a logistics context where something’s gone missing. Try using it to describe the whole context for mobile, social, programmable-hardware, an assembly-line, even a data-centre – let alone anything that centres more around physical-machines or people. It doesn’t work: many if not most of the entities we need simply don’t exist in the metamodel – and its arbitrary, unexamined assumptions just get in the way.

In other words, it’s yet another darned term-hijack. Frustrating, to say the least…

– Predictable-world versus complex-world

The BDAT-stack and the TOGAF metamodel lead inevitably towards an IT-centric architecture. Which is fine, of course, in those specific cases where the IT is the centre of concern – but a huge problem when it isn’t.

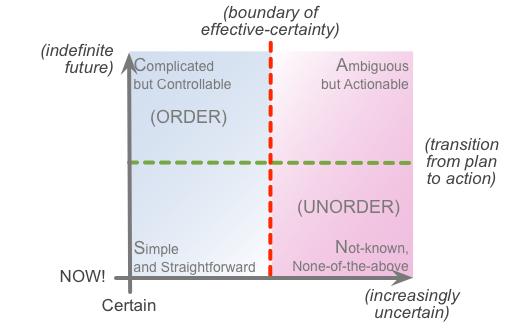

One of the more subtle dangers of IT-centrism – or anything-centrism, actually – is that it tries to remake the world into its own image, constraining our view of that wider world. In the case of IT-centrism, the only world it can handle is one that is built around predictable rules and algorithms – a world of order, as indicated on the left-hand side of the SCAN frame:

The real-world, however, always includes ambiguities, uncertainties and other forms of unorder. Which means that a framework that barely acknowledges even the existence of such things – let alone their real-world prevalence – is inevitably going to be deeply misleading.

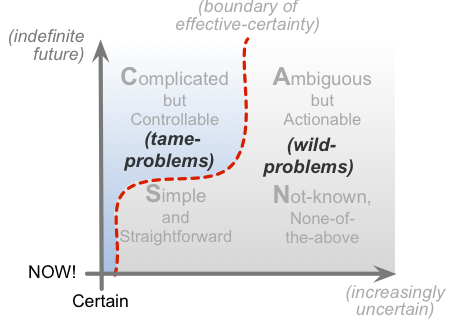

More than that, on its own IT can only handle tame-problems – problems with a definite true/false answer. The reality, though, is that the real-world consists primarily of ‘wild-problems‘ – of which seemingly-’tame’ problems are merely an often-illusory subset, subject to ‘variety-weather‘, ‘requisite-fuzziness‘ and similar deep-uncertainties:

IT is great for mass-sameness, of course. The catch is that the very characteristics that make it great for mass-sameness are those that make it often deeply-unsuited to mass-uniqueness – which, in reality, resides right at the core of many industries and domains, such as healthcare, customer-service, retail, marketing, sales, agriculture and information-search. The inherent IT-centrism of TOGAF and the like is really unhelpful whenever we need to develop enterprise-architectures for such domains.

– Predefined reference-architectures versus how to create a reference-architecture

Yet another frustration: reference-architectures. At present, the two TOGAF reference-frameworks – TRM and IIIRM – are both so long out-of-date that at one Open Group conference, Allen Brown himself recommended that they should be dropped.

But rather than a mere replacement reference-architecture that will likewise go out of date in a couple of years at most, what we most need instead is advice on how to create and maintain a reference-architecture – perhaps using the existing TRM and IIIRM as worked-examples. We also need such reference-architectures to explain their respective ‘It depends‘ constraints and variances – at least to the level of the MoSCoW set, as a minimum.

Yet there’s still almost nothing at all on that in the so-called ‘standard’. Bah.

– Apprentice-level versus journeyman-level

This is another subtle one, though in part it follows directly from the IT-centrism problems above. More specifically, though, it’s about where TOGAF and, in particular, TOGAF training sit on the skills-development spectrum:

Where it sits is primarily at the earlier stages of the Apprentice phase, where the learner is just starting to move out of ‘follow-the-instructions’, and move ‘upward’ into the first levels of the theory behind those instructions. Yet the focus is still on rote-learning, ‘by the book’: it’s all theory, there’s no requirement for real-world practice.

And without that grounding in practice, there’s a huge, huge risk of ‘illusory superiority‘ – delusions of assumed competence that just does not exist in reality. The danger – and I’ve seen it displayed way too often, on LinkedIn and elsewhere – is that ‘newbie’ TOGAF trainees have just enough knowledge to get into serious trouble, and nothing like enough knowledge to be able to get out of that trouble on their own, yet believe that they alone know everything about enterprise-architecture. In too many cases, the only way to bring such people out of their over-certainties, and on towards the journeyman-level skills that they need for real-world enterprise-architecture, is to get them to unlearn every scrap of what they’ve learnt on their TOGAF course, and start again from scratch. A heck of a waste of effort all round… and a huge frustration in dealing with wave after wave of – let’s be blunt – idiots who think they know everything about enterprise-architecture solely because they have a TOGAF certification to wave around. Sigh…

– Rote-learning certification versus skills-certification

Certification, ah, certification… probably the biggest bugbear about TOGAF that most of us have in enterprise-architecture, bluntly.

The TOGAF certification comes in two parts: Level 1 (Foundation) and Level 2 (Certified). In essence, Level 1 tests whether the candidate knows the terminology; Level 2 tests knowledge of the full specification.

Both of them are only at a rote-learning level: they can’t be more than that, because a TOGAF training-course is only a few days’-worth at most. There’s no skills-test at all – and the whole thing is tested via machine-based multiple-choice exam, which is exactly how not to test for skills-knowledge.

Given – as above – that several key parts of the TOGAF specification are not merely incomplete but just plain wrong, then all that ‘certification’ means is that someone has read wrong material well enough to pass a multiple-choice exam that has no connection whatsoever to any real-world context.

(Yes, I do know that Open Group’s ‘Open-CA’ certification does require real-world knowledge. TOGAF certification doesn’t: it solely tests rote-knowledge of the book itself, not real-world knowledge – in fact answering the test-questions correctly in terms of real-world practice will often incur a penalty on the test-score. Sigh…)

So in effect, TOGAF certification tests whether you’ve learnt the content of the book, which itself doesn’t connect much or, in some areas, at all, with real-world practice – in other words, not far off a work of wistful fiction. And, starting from that already largely-fictional story, it then demands true/false answers for decision-contexts that in real-world practice are always riddled with ‘It depends’ contextualities. In what possible way could anyone claim that that would be anything other than meaningless, or worse?

Yet various folks still seem kinda uncomfortable about that kind of interpretation:

The certification itself, like any certification, can’t mean any more than that [someone has been tested for rote-knowledge], and doesn’t purport to.

Correct that it can’t mean any more than that, and certainly that it shouldn’t. But given that just about every lazy darn recruiter uses the TOGAF ‘certification’ as a tick-the-box test not just of purported knowledge but of competence and skill, and that Open Group and, even more, its trainer-community actively promote it as such, we know that that assertion that “doesn’t purport to” is just not true. It’s arguable that the implications of that fact are primarily Open Group’s problem, not ours – but I really do wish that they’d do something more useful about it than merely trying to silence the critiques and pretend that the problem doesn’t exist…

Instead, if perhaps unsurprisingly, Open Group seem very happy about TOGAF certification, as evidenced in this Tweet from a few days ago:

- TOGAF 9 Certification News: Total passes 37,000. Level 1=11445, Level 2=25878 http://ow.ly/DFg6E

And yet I don’t know whether to celebrate on their behalf, or weep for the rest of us. The latter, mostly… This supposed success of TOGAF in the marketplace is actually a ‘success’ that, as we can see from all of the above, is built on exactly how not to do ‘the architecture of the enterprise’ – which means that the real mess is getting worse with every passing day. For everyone’s sake, it really is time that all of us should call a halt on the TOGAF hype-machine, and put that bewretched ‘EA’-framework back into the IT-only box where it does and must belong.

Okay, you might think that a lot of those complaints above might seem a bit extreme: TOGAF does have some value, after all, if only for some specific types of IT-architecture. As one participant in a LinkedIn thread commented:

lets not throw the baby out with the bathwater

Yet for ‘the architecture of the enterprise’, turns out there is no baby in the TOGAF bathwater – just a rubber duck, a worn-out blob of soap, and a couple of mismatched socks left over from last week’s washing. Nothing much that’s worth keeping, anyway.

Storm in a bathtub, mostly. But with a lot of money riding on it, hence a lot of dollar-laden delusions too.

“Why do I loathe thee, TOGAF? Let me count the ways…” Well, that’s some of the ways and whys, anyway.

Bah.