Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2015/02/10/on-modelling-selfservice-w-archimate/

In enterprise-architecture, how should you describe or model ‘self-service’ – in which the customer, rather than the organisation’s employee, uses the organisation’s systems to place an order, or search for information?

The classic way of looking at this is from an ‘inside-out’ view – or, more usually, ‘inside-in‘, where company staff are considered to be the only users. But that doesn’t work in this case: the customer is not only an ‘outsider’ relative to the organisation and its systems, but is literally outside of the organisation’s control.

Gerben Wierda – grand-master of modelling with Archimate, and author of ‘Mastering Archimate‘ and ‘Chess and the Art of Enterprise Architecture‘ – picked up on this point via a LinkedIn post by Samuel Holcman, ‘Inside Out vs Outside In Enterprise Architecture‘. Gerben’s first response was a post on his Enterprise Chess website, ‘“I Robot” – There Is No Such Thing As ‘Customer Self-Service’‘:

The issue [that Samuel Holcman] raises is that the clients of organisations more and more seem to become the ones that perform the organisation’s processes (e.g. self-service), and that they thus should be taken into account as parts of the architecture of your organisation. Some even speak about the ‘extended enterprise’ in that context. I have been disagreeing with that view for a while, and this is a nice occasion to put that in writing.

(I suspect that one of the “some [who] even speak about the ‘extended enterprise’” would include me, but that’s not a point I need to go into here!)

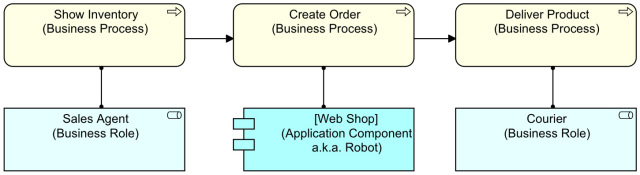

Within that post, Gerben laid out a handful of intentionally over-simplified Archimate models to illustrate that a simple substitution of internal order-clerk to external customer doesn’t seem to make sense in formal Archimate terms. Instead, he proposes that it makes more sense to say that the order is still actually placed by an internal ‘employee’ – but a robotic employee in this case, as represented by the respective functionality of the website:

It’s not the customer that is acting in our landscape at all, he is just interfacing with us.

He then adds a few notes about the ‘big-picture‘ implications of such robotic-employees, which personally I’m very happy to see, but again don’t relate much to the point that I want to explore here. The point that I do want to explore relates to the admittedly quick-and-dirty Archimate model with which Gerben ends up in that post:

What we have here, in effect, is a computer-based application – an Application Component, in Archimate terms – as a direct substitute for the human Business Role of Order Entry Clerk.

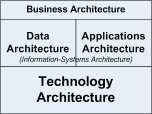

Stop and think about that for a moment, in terms of the classic ‘BDAT-stack’ (‘Business’, ‘Data’ plus ‘Applications’, and [IT-specific] ‘Technology’), as used in Archimate, TOGAF, and darn near every one of the mainstream ‘enterprise’-architecture frameworks:

What I’d hope you’d notice from that cross-comparison is that everything in Gerben’s diagram above is, in classic terms, part of the Business Architecture layer: Gerben’s ‘Robot’ is a direct substitute for a Business Role. But yet the BDAT-stack says that it can’t do that, because applications can only be in the Data/Applications layer. So the Robot is kind-of in both layers, but also in neither, both at the same time…

Gerben being Gerben, he spots that problem straight away – hence the follow-on post on his Mastering Archimate website, ‘Modelling Self-Service In Archimate‘. And quietly demonstrates, through a series of descriptive diagrams, that the current version of Archimate simply will not allow us to model this now very common business-pattern. Not in any Archimate-’legal’ way, anyway.

Oops.

Again, Gerben being Gerben, he shows that once we do allow certain adjustments and adaptations to the Archimate syntax, we can sort-of just-about make it work – though all of it is somewhat of a kludge, and even then perhaps only works as long as we stick to an strict IT-centric and organisation-centric view of the context. Yet as he also shows, and highlights, there really is no way to get round the fact that in that scenario, one of the Business Role entities is actually what he calls a Robotic Role – but in a place which, according to the Archimate layering, can only be done by a human. Hence, as he says in the Conclusion section to that post:

The common layered approach of enterprise architecture, also part of ArchiMate, is creaking at the seams. Applications are used as robots at the business level. And the infrastructure layer is currently transforming to software-defined anything. We might need a wildly different approach for this brave new world.

To which I would strongly agree…

Yet I’d actually say that we need take it even further than that – a lot further. That’s because, in reality, “the common layered approach of enterprise architecture” is a truly horrible mess of arbitrary assumptions and arbitrary conflations:

- ‘Business‘ = anything-human + anything-relational + principle-based (‘vision/values’) decisions + higher-order abstraction + intent

- ‘Applications/Data‘ = anything-computational + anything-informational + ‘truth-based’ (algorithmic) decisions + virtual (lower-order ‘logical’ abstraction)

- ‘Technology‘ = anything-mechanical + anything-physical + physical-law (‘rule-based’) decisions + concrete (‘physical’/tangible abstraction)

(It’s even worse than that, because in most variants of ‘the common layered approach’, we can’t even describe any technologies other than electronic computer-type IT.)

The result, as I’ve described elsewhere, is that it’s always been all-but-impossible to use ‘the common layered approach’ to describe even quite routine enterprise-architecture concerns such as business-continuity/disaster-recovery or data-centre design – let alone the kind of concerns I regularly deal with in my own work that address physical-technologies and multi-channel transmedia business-models and the like, or upcoming technologies such as programmable hardware and smart-materials. Yet as Gerben shows, ‘the common layered approach’ is so limited and constrained that it can’t even handle current IT-based business-models such as an e-commerce website, where an Application inherently also acts as a Business Role.

Hence it’s not that ‘the common layered approach’ is “creaking at the seams”, as Gerben puts it: instead, it’s more that ‘the common layered approach’ is completely broken, at a fundamental level, right down to its deepest roots – and always has been. Yes, at one time it might well have seemed convenient, from an IT-centric perspective: but even back then, it was an IT-centrism that merely reflected certain arbitrary unquestioned assumptions about the nature of the IT of that time, which were all but guaranteed to fall apart at some future point in time – which is exactly what’s happening now. For any architecture that’s needed to centre around anything other than that classic ‘big-IT’ – which happens to be perhaps 95% of any real ‘architecture of the enterprise’ – that ‘layered approach’ was always the wrong way to do it: a fact that we, as a discipline and profession, we really do need to face right now.

Yes, I’d agree that the BDAT-stack, and ‘the common layered approach’ in general, has been useful in the past, and is still possibly-useful for certain decreasingly-common specialist purposes. For anything else, though it’s a chimera, a booby-trap riddled with potentially-dangerous delusions. Reality is that the BDAT-stack has long since passed its ‘use-by’ date: it’s time to drop it – and instead reframe our architecture-frameworks around the ways that all other architectures actually work. Please?