Link: https://eawheel.com/blog/2026/01/architecture-beyond-domains/

From EAWheel

Enterprise Architecture has been around for decades. The discipline has profoundly shaped how organizations plan, align, and structure their strategies, systems, and operations.

Frameworks such as the TOGAF Standard define four architecture domains — business, data, application, and technology — and link them to specific architectural roles. While this approach has helped organizations organize work, it has also unintentionally reinforced rigid silos and limited the true potential of architecture as a holistic organizational capability.

It’s time for a more modern approach. This approach should consider the architecture beyond domains. Instead of focusing on parts, it should focus on the whole.

What Are Architecture Domains?

First, let’s take a step back and look at what we mean by architecture domains. Traditionally, architecture frameworks break Enterprise Architecture into four primary domains:

- Business Architecture: defining and aligning the organization’s business strategy, governance, and processes.

- Data Architecture: organizing the structure and management of data assets.

- Application Architecture: describing the applications and their interactions.

- Technology Architecture: detailing hardware, platforms, and infrastructure.

This has become conventional wisdom. Courses teach it. Tooling models reflect it. Job descriptions often list architects by domain (e.g., Data Architect, Application Architect). At first glance, this seems sensible: separate concerns, give each area its own expertise, create manageable work units. But this domain split has a hidden cost.

The Problem with Domain-Based Thinking

When architecture is thought of as separate domains, teams often organise themselves around those domains. Business Architects work in one silo, Data Architects in another. Application Architects in yet another. Each group becomes responsible for their piece of the puzzle, not the puzzle as a whole.

But organizations aren’t siloed. Business goals don’t occur solely within business architecture, data challenges don’t happen only inside data architecture, and technology decisions don’t stop at the tech team’s door. Real change initiatives cross these lines.

Siloed domain thinking risks people owning pieces but none owning the whole. And when no one owns the whole, the result is inconsistent decisions, misaligned strategies, and duplicated work — precisely the problems EA should prevent.

Narrowing the Scope

One direct outcome of domain partitioning is that each architectural role becomes narrowly scoped:

Business Architects stick to business, Data Architects stick to data, Application Architects stick to applications, Technology Architects stick to tech.

This segmentation suggests — implicitly — that Enterprise Architects shouldn’t worry about technology, Solution Architects shouldn’t worry about data, and so on.

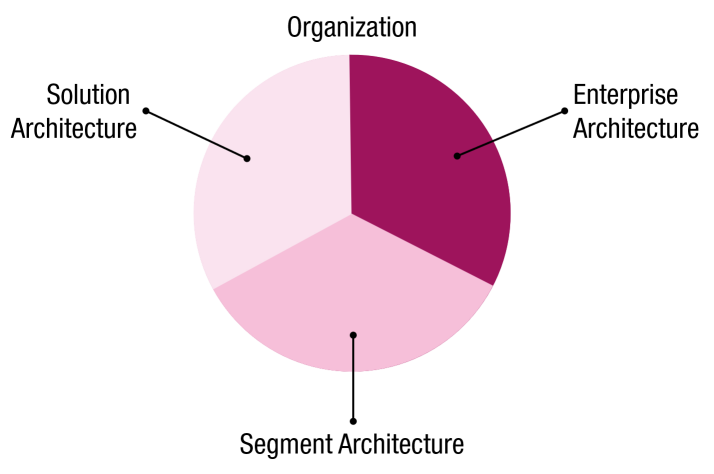

But modern organizational challenges don’t respect such boundaries. If an Enterprise Architect proposes a strategy that fails due to technology choices, the blame shouldn’t be in technology’s domain. Likewise, Solution Architects often make decisions that shape strategic direction — even if they are framed as “project” or “solution” work. The effect? Roles become limited players rather than holistic architects. Responsibility becomes fragmented, and real strategic coherence suffers. This narrow scope is illustrated in Figure 1.

Check-the-Box Architecture

A common misconception — even among seasoned practitioners — is that Enterprise Architecture is about producing artifacts: diagrams, models, matrices, and deliverables. This is especially true when architecture is framed around domains, each with its catalogue of domain-specific outputs.

But architecture should be about insight, guidance, and alignment, not just documents. Misunderstood frameworks often lead practitioners to believe the method is documentation-centric when in reality, good architecture is about effective communication and decision-making.

Domain splits can exacerbate this, inadvertently pushing teams toward producing stuff for the domain rather than insights for the organization or enterprise.

Holistic by Definition

Enterprise Architecture, and let’s underline this, exists to address the enterprise as a whole. This is not just semantics. According to leading definitions, Enterprise Architecture is a practice that:

applies architecture principles and practices to guide organizations through business, information, process, and technology changes necessary to execute strategy, and it proactively and holistically lead[s] enterprise responses to disruptive forces. – Gartner & FEAPO

Notice the emphasis on holistic leadership and enterprise-wide perspective — not compartmentalised domains. Enterprise Architecture is not a portfolio of isolated domain specialties. It is a systemic function that coordinates across the organization’s interconnected components.

Architecture must bridge organizational problems and challenges — not fence them off.

An Organization-Wide Lens

Instead of domain-centric Enterprise Architecture, I believe it’s more powerful to consider roles by scope of responsibility across the organization:

- Enterprise Architect

- Owns the big picture.

- Aligns strategy with architecture principles.

- Guides organization-wide architectural thinking and decisions.

- Oversees major strategic initiatives and interdependencies.

- Segment Architect

- Focuses on a coherent organizational segment while keeping the entire organization in mind.

- In that context, creates architectural roadmaps, governs change, and ensures alignment up and down the hierarchy.

- Connects enterprise strategy to segment execution.

- Solution Architect

- Works at the project or solution level, while maintaining an organization-wide perspective.

- Designs specific solutions, but always within the context of broader organizational architecture principles.

- Bridges detailed technical decisions with segment and enterprise expectations.

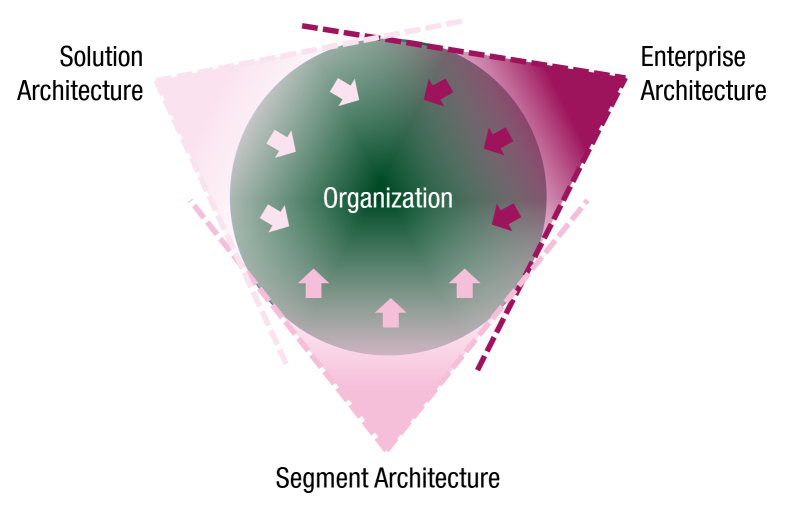

These roles represent levels of scope, not distinct domain silos. Each role touches all architecture concerns, but at different levels of granularity and organizational influence. In other words, they all view the entire organization, rather than just a piece of it, from their own perspectives. Figure 2 shows how this modern lens is used.

This is fundamentally different from saying “Business Architects do business, Data Architects do data, etc.” Instead, each role answers: what does this organization — not just this domain — need?

Viewing Architecture Holistically Improves Outcomes

When Enterprise Architects, Segment Architects, and Solution Architects share a view of the entire organization, decisions become cumulative rather than conflicting.

- Enterprise Architects set principles and direction.

- Segment Architects translate those into roadmaps and priorities.

- Solution Architects implement decisions that fit both strategic intent and real-world constraints.

This ensures consistency and reduces friction between planning and execution.

Compare that to domain-based roles where, for example, a Data Architect’s decisions about data structures might unwittingly conflict with an Application Architect’s decisions about application interfaces, simply because neither is empowered to see the end-to-end impact.

What This Means for Common Frameworks

The TOGAF Standard — the world’s leading architecture framework — has evolved over decades and includes the Architecture Development Method (ADM) that guides architectural work across phases. Coincidentally, it is the same framework that defines the four architecture domains, resulting in a limited, siloed approach.

Although The Open Group’s motto is “boundaryless information flow”, their TOGAF Standard divides architecture into four domains, which creates hidden boundaries, the very thing they want to avoid.

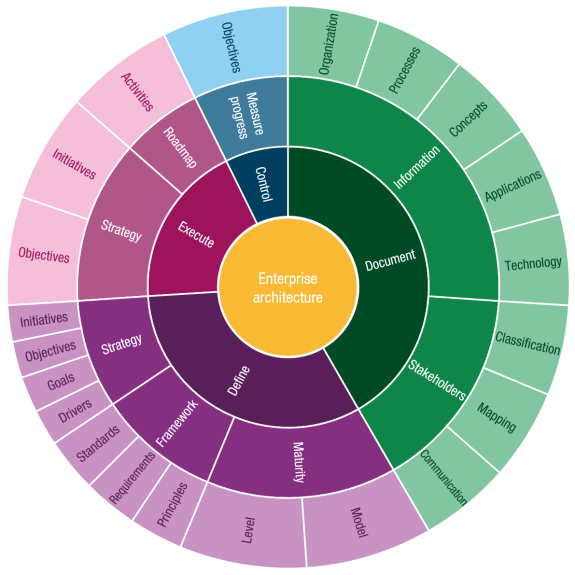

Which brings us to modern alternatives like the Enterprise Architecture Implementation Wheel.

A More Modern Approach to Architecture

The Enterprise Architecture Implementation Wheel is an approach that reframes HOW architecture is practiced — not by domain labels, but by organizational purpose and stages of work. It positions architecture as a central function that radiates outward through practical stages such as documenting, defining, executing, and controlling architecture.

Rather than partitioning architecture, the Enterprise Architecture Implementation Wheel model centres architecture as the guiding force and structures the work around cycles of understanding and refinement.

As opposed to domain pass-offs, the Implementation Wheel encourages continuous loops of validation, measurement, and alignment across organizational concerns.

Keeping Roles in Context

Enterprise, Segment, and Solution Architects all play into these stages, but no one is limited to a piece of the architecture in isolation. They are instead participants in a shared organizational narrative.

The Enterprise Architecture Implementation Wheel approach is a more modern fit for organizations that operate in dynamic environments where cross-domain interdependencies are the rule, not the exception.

It Is About Value, Not Labels

Enterprise Architecture doesn’t derive value from how clearly we can define domains. It derives value from how effectively we guide decisions, enable change, and drive outcomes across the organization.

Domains can be useful for organizing knowledge and framing expertise. But when they become rigid dividing lines, they limit architectural influence, slow down alignment, and fragment ownership of strategic outcomes.

By viewing architecture through the lenses of organizational scope — from the whole enterprise down to specific solutions — organizations enable architects to contribute at every level with awareness of the broader context, and ensure architecture truly serves the business as a whole.

This is not merely a semantic shift. It’s a practical reorientation that honors what architecture is truly designed to do: connect strategy, structure, and execution across the entire enterprise.

The post Architecture Beyond Domains appeared first on EAWheel.