Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2012/08/08/sensemaking-and-swamp-metaphor/

One of the core tasks in enterprise-architecture is sensemaking – making sense of what’s going on within some context. And one of the key methods we can use for this is to make some kind of mental-map of what seems to be going on in the context – hence ‘context-space mapping‘ (CSM).

Over the years I’ve used many different frameworks and models for this process. In essence, once we understand how context-space mapping works, we can use almost any kind of model we’d come across in business or elsewhere – SWOT, Six Sigma, Cynefin, Causal Layered Analysis, Porter Value-Chain, PDCA, OODA, Five Element, Five Whys or just about anything else.

Yet one frame I keep coming back to – and which underpins much of my recent work on SCAN and the like – is a variant of one of Carl Jung’s models, a simple two-axis matrix of ‘truth’ versus ‘value’, and ‘inner’ versus ‘outer’. I would probably have first come across it in the late 1960s or early 1970s: for example, I know I used as a core guide in the skills-research that led to my my first book, way back in 1976.

For me, though, the real breakthrough was its adaptation as the ‘swamp metaphor’ in the anonymous book SSOTBME, which I first came across somewhen in the late-1970s. I described this metaphor a couple of years ago, within an earlier post about background; but given its relationship to SCAN, it seems worthwhile to pull that description back from the archives and re-publish it here.

The swamp-metaphor

With the author’s permission, I included my own version of the SSOTBME swamp-metaphor in my 1986 book ‘Inventing Reality‘. [The quotes below are from the 1990 edition.] I’ll quote first from the lead-in section, in the chapter ‘Can’t we explain this scientifically?‘:

[A rather lengthy aside seems necessary at this point. When I first came across Dave Snowden’s work on the Cynefin framework, nigh on two decades after I wrote the first edition of Inventing Reality, I saw what seemed to me to be an obvious parallel there: Cynefin’s central domain of ‘Disorder’ as the overall swamp, the precursor before sensemaking occurs, and then each element of the Cynefin frame mapped to one of the Jungian elements – Known/Simple to inner-truth, Knowable/Complicated to outer-truth, Complex to outer-value, and Chaotic to inner-value. (The mapping makes more sense with the full swamp-metaphor, as we’ll see later.) The curved-boundaries in Cynefin seemed to emphasise the dynamic and recursive nature of sensemaking, too; so, like a fair few others at the time, I started to use ‘Cynefin’ in this sense in enterprise-architecture and elsewhere.In the last chapter [‘Isn’t it all coincidence?’] we saw that coincidence and meaning are quite separate – we can’t really say that any thing or any co-incidence can be said to be caused by any other event, point of view or whatever. Anything goes.

The trouble with that concept is that if anything goes, we are left with nothing with which to make sense of the world. Without some way of handling it, we have no way of predicting anything at all, and everything and nothing happens at the same time – a certain recipe for instant insanity. So we need some kind of model which allows us the flexibility to allow anything to happen, yet still operate in something resembling a controlled manner.

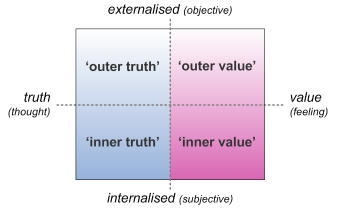

One approach which is useful is to separate the information we experience from its interpretation, and describe this content and context each as an axis in a simple two-dimensional diagram. In one direction, we have a spectrum of information, ranging from outer tangible or sensory data, to information we derive from within ourselves, as feelings and intuitions. The other axis describes a range of methods of interpretation, from indefinable value judgements through to the strict true/false analyses of logic: a spectrum of interpretation between value and truth – whatever either of those might mean. The model looks something like this:

This gives us four quadrants, or modes, in which we both collect information and interpret it: inner value, inner truth, outer truth, outer value. Each of these quadrants is only a way of working on the world, a mode to describe reality as we experience it through using that way of interpreting the world. Reality is, if you like, the sum of everything that could be experienced through these four very different ways of working on the world.

Unfortunately, as evidenced in a series of increasingly-acrimonious exchanges here, Snowden didn’t accept that parallel at all; and it also slowly became clear that, for enterprise-architecture, the ‘official’ version of Cynefin had serious limitations anyway, especially in what it termed the Chaotic domain. Hence the need for a fundamental rethink, with an explicit distancing from Cynefin as I developed the descriptions of context-space mapping and, later, the SCAN framework. I’ve also been quietly ‘deCynefinating’ the text in the newer e-book editions of my books. However, there’s still a lot of older material here and in my books that still refers to Cynefin in this supposedly ‘illegitimate’ sense: so whenever you see a reference to Cynefin there, it’s probably best to assume that it relates more to this Jungian frame and, in particular, the swamp-metaphor, rather than to ‘Cynefin proper’.

Anyway, to continue the quote from Inventing Reality.]

This kind of model of reality can be found in Jung’s work, for example; but there is a particularly interesting variant on the theme in SSOTBME, a bizarre book on ‘thinking about thinking’. The book was published anonymously, so, for convenience, I shall refer to its author as Leo (a simpler name than his fictitious character Lemuel Johnstone).

Leo builds this model by describing the whole of reality as a swamp. Not a featureless swamp – every point of view, every experience, every possible coincidence of events is included. There are also endless opportunities to wallow in the mires of confusion, and to disappear beneath the surface without trace… It sometimes seems that the safest move would be not to move at all, to stay still. But even that isn’t certain: the surface seems to quake with the tide of events, so that even the safest-seeming point of view will seem doubtful after a while. Nothing stays the same for long: indeed, the only real constant is change itself.

As Leo puts it, there are four main ways in which to exist within this kind of reality. Each one coincides with a quadrant of the model above: inner value, inner truth, outer truth, outer value.

Each is best described as a mode of operation, in which certain possibilities – such as movement, in this sense of moving from one point of view or one experience to another – exist solely because others – such as stasis, developing one particular point of view – do not occur.

The four modes are structurally different: they have different definitions of success, of value, of proof and so on. In most cultures one of these modes will tend to dominate over the others, often for long periods, but that dominance does tend to drift over time: one of the key points discussed in SSOTBME was the ‘Enlightenment’-period transition from dominance of the simple religion-based ‘inner truths’ to the more complicated ‘outer-truths’ of science.

Sensemaking as the Artist

The description of the four modes or domains in the swamp-metaphor starts with the chaotic world of the Artist:

The first way of working on this world is to skim the surface of the swamp, travelling in a hydroplane at high speed. The whole point is the speed, and the variety of ideas and experiences that come from just travelling about with no particular place to go. This is a mode of inner value, which we could call the artistic mode.

Playing with this description a little further, we can see that this is hardly a safe way of operating within a swamp: it’s all too easy to crash into some unexpected experience, to run out of fuel (inspiration?), or to decide to settle down in some uncharted spot with no hope of future supplies or common experience shared with anyone else. But it’s certainly the quickest way of scanning a wide range of experiences and points of view – although, at that speed, it’s not going to be too easy to make sense of anything other than that they were, indeed, experiences and points of view.

We don’t always need a hydroplane, of course: sometimes – like that lizard that can run over water – the Artist can sort-of keep afloat by running really fast… ![]() I’d have to admit that of all the modes, this is the one to which I would naturally tend to return, not least because it aligns well with my eclectic, always future-oriented, and yes, somewhat scatterbrained approach to life and work: for example, I keep coming across articles that I wrote even only a month or two back that I have no recollection of ever having written at all.

I’d have to admit that of all the modes, this is the one to which I would naturally tend to return, not least because it aligns well with my eclectic, always future-oriented, and yes, somewhat scatterbrained approach to life and work: for example, I keep coming across articles that I wrote even only a month or two back that I have no recollection of ever having written at all. ![]() But it does work well, as long as we can link it to the other modes enough to get something actually done with all of those ideas.

But it does work well, as long as we can link it to the other modes enough to get something actually done with all of those ideas.

Sensemaking as the Believer

Next, we swap over to the other side of the SCAN frame, as the Believer:

Another modus operandi seems quite the opposite of the artistic one: to develop one point of view as far as it will go, right out into another dimension. You state that that point of view is true – inviolably and absolutely true – and build on it, like a pole in the swamp. This is a mode of conviction, of faith, of inner truth – the mystical or religious mode.

Again, playing with this image a little further, the higher you climb up the pole, the more of the swamp will come within your view: the more you climb, the more true will seem the point of view. In the distance you can see other poles, other points of view – some of them way out in the distance indeed – but you can hear that experiences from those poles, especially from further up each pole, seems much the same as your own. The mystics, those people who are well and truly up the pole and with their heads in the clouds, can see and share a vast range of vision – even though most of it seems like cloudy thinking to us.

The only trouble with this mode is that you can’t actually experience anything else, since, by its definition, you have to stay with that one point of view; and it seems a sad fact that each pole has to be counterbalanced by a vast morass of struggling bodies, each of whom has grasped the pole and disappeared beneath the surface, screaming “I have the truth” as they did so.

There are several variants of this mode (and the other modes too, for that matter), which are probably easiest to understand as recursions of the same overall frame as applied to a single mode or ‘domain’ within the swamp-metaphor frame.

For example, as above, there’s the Mystic – the only one here who actually does get a high-level overview from that position. In essence, that’s inner-value applied to inner-truth, exploring everywhere, like an artist, yet via looking inward always into the same space. This is perhaps best typified by chapter 47 of the Tao Te Ching: “Without going outside, you may know the whole world. / Without looking through the window, you may see the ways of heaven. / The farther you go, the less you know.”

Another variant, as also above, is the Believer, who – to be somewhat unkind – is sometimes the kind of dead-weight that’s used to prop the whole thing up. (Remember that the ‘One Truth’ here need not be an explicit ‘religion’ as such: for example, many self-styled Skeptics are ‘Believers’ relative to some often very-scrambled notions of what science actually is and does.) We could perhaps view that mode as ‘inner-truth squared’ – rigidly-internalised truth, applied to everything.

Another is the Priest, who stands at the foot of the mystics’ pole, without any of the mystic’s broad overview, but who sets out the interpret to mystics’ visions from this ‘One Truth’ into simple rules to be upheld by ‘the masses’ (the Believers). In effect, this is inner-truth interpreted as outer-truth, and the danger is that it can be extraordinarily arrogant and egocentric: one’s own personal-truth aggressively imposed others as a purported ‘The Truth’, demanding the suppression of every other possible view. For example, think of someone like a would-be Jesuit priest, often highly charismatic, a real commitment to ‘those of the faith’, a genuine commitment to do ‘good works’; yet beneath the surface there can be a dangerous fanaticism, a screaming hatred of ‘heresy’, perhaps all ultimately driven by a deep fear that the chosen ‘One Truth’ is actually nothing more than an arbitrary choice – that the ‘One Truth’ might not, in fact, be the Truth at all. Whenever that mode gets entrenched as someone’s primary mode of thought, watch out: such people are the direct source of ‘religious wars’ in every sense, and all too often are literally deadly to others… You Have Been Warned?

And finally there’s also the Miner, searching for the outer-value of inner-truth. In effect, this is almost the opposite mode to that of the Mystic: where the Mystic reaches up into the aetherial realms, the Miner digs deep into the ground beneath this ‘one true place’ to find the riches hidden beneath the surface – but may well do serious damage to the place itself in the process of that quest.

The other point, perhaps, is that – somewhat like the Artist, but often in more covert fashion – there’s often a deep intensity of emotion here. It’s one of the key ways, in fact, to distinguish between science and the pseudo-scientific religion of ‘scientism’: as soon as emotion enters the picture, it ain’t science any more – which is something we need to watch when we get excited about ideas in science! ![]()

Sensemaking as the Scientist

The next character we meet in the swamp is the Scientist, who loves to deal with complicated detail:

The third mode in this model is to build a solid platform, a safe predictable area in which everything is true and inter-related in logic. Everything is patently obvious, there are no surprises on the platform itself – although around the edges things may not be quite so predictable as they seem. This is a world of outer truth, a scientific world.

To many people on the platform, the platform itself defines reality, and encompasses the whole of truth. To this point of view, which we could call public-science or ‘scientism’, anything beyond the platform is unreal; their duty is to build higher and higher walls around the platform, to protect the good citizens from the ignorance and superstition beyond. In fact this has very little to do with science as practised – we could suggest that these are same people who would have screamed “I have the truth” around the poles of religion, except that the solidity of the platform prevents them from decently disappearing beneath the surface as would have happened elsewhere.

The platform is woven between a group of poles, more often called the ivory towers of academia; their mystics are the ‘pure scientists’ whose breadth of vision is matched only by the impenetrability of their thought. And at the edge of the platform are practical scientists, researchers working at the limits of the known world – having discovered, by some means or other, some unintended hole in the fortress walls of scientism.

Scientists, says Leo, are like people in wheelchairs – they need firm level ground to move about on. To move, they must extend the platform, extending the boundaries of science, cutting down shady dogmas and filling in soggy hypotheses (to use Leo’s graphic image). But when they arrive at some new place, it is just as boring and predictable as anywhere else on the platform – hobgoblins and foul fiends having rushed away at the sound of the first myth being exploded. For the problem with this mode of working is that, by the time it has finished, what it seeks has ceased to be the swamp, has ceased to be reality as it is (or was) – it is just an artificial platform, an ‘objective’ world with no room for personal experience at all.

One important point to note here is that the world of the Scientist is an abstraction, an often over-simplified, levelled-out overlay on top of the messy complexities and uncertainties of the swamp. The apparent certainty of science is actually a sham: very few scientific ‘laws’ apply with absolute precision in the contexts within which they purport to apply. For example, Leo, the original author of the swamp-metaphor, said that one of his most difficult challenges as a mathematician working in aircraft-design was to find ways to make his mathematics sufficiently imprecise to be useful. But that comforting sense of certainty is beguiling: we do need to beware of the tendency to think that the real world is somehow ‘wrong’ if it fails to conform to the expectations of theory… Safe though that platform may seem, there are real dangers here which are easily missed by the unwary.

Sensemaking as the Technologist

Continuing our wander through the swamp, we come across the last of these four main modes:

But working away at the edges of the platform are another group, commonly but quite wrongly called ‘applied scientists’. At one edge you’ll find the psychiatrists, not bothering too much about which theory is absolutely true, but using ideas from Jung, Adler, Freud, Laing and anyone else’s work they can lay their hands on. And at another edge there’ll be electrical engineers switching between wave and particle theories of light and energy, blithely unconcerned about their mutual incompatibility in logic.

At first this does look like science, but only because of the safety-line of ‘if it doesn’t work, go back to theory’ – in other words go back to ‘outer truth’. But in fact this is a quite different mode, in which you carry the platform with you, spreading your weight on swampshoes to allow you to move with relative freedom from place to place, idea to idea, to find a point of view which is useful at that time, rather than supposedly ‘true’ in any absolute sense.

This is a mode in which truth is defined in terms of whether it has practical value, outer value. We could describe this as a technological mode.

Yet there’s a very important twist here – an outcome of another of those recursions where we apply the model to itself:

But it has a shorter and easier label – a magical mode. Whilst there is a real structural difference between technology and science, there is no structural difference between technology and magic.

It’s entirely true that, as Arthur C. Clarke put it, “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. But it’s also true that “any sufficiently advanced magic is indistinguishable from technology”. They may seem different – sometimes very different – but the underlying approach to reality is exactly the same. The only difference between technology and magic, in practice, is that magicians tend to be a little way out in the distance – they may be seen wandering to astrology, alchemy and other forgotten, part-ruined areas of the old platforms of science, to rest by some religious pole, or travel as fools where angels fear to tread.

This mode is hardly safe, as the platform of science may be, but at least it works on the swamp as it is; and the point of the exploring is not to find out how true a belief, a point of view, may be, but to put it to practical use.

This linkage between the Technologist (as the outer-value of the external world) and the Magician (perhaps more as the outer-value of the internal world) does seem to upset some people – particularly those Priest-mode types who like to think of themselves as ‘scientists’. But in practice it is real: the differences between technology and science are fundamental, whereas there is no such fundamental difference between technology and ‘magic’.

SCANning the swamp

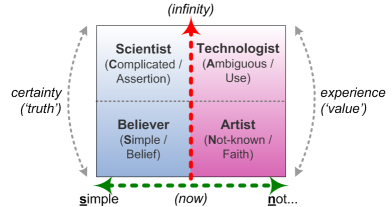

There’s a direct and straightforward mapping between the swamp-metaphor and the SCAN frame:

- the ‘truth’ versus ‘value’ dichotomy maps exactly to the differences we see either side of the Inverse Einstein Test, the boundary between Simple/Complicated versus Ambiguous/Not-known

- the ‘outer’ versus ‘inner’ dichotomy maps to the distinctions between ‘considered’ versus ‘real-time’ sensemaking and decision-making

Which, in effect, gives us the following mapping:

- Simple/Belief maps to inner-truth/religious

- Complicated/Assertion maps to outer-truth/scientific

- Ambiguous/Use maps to outer-value/technological

- Not-known/Faith maps to inner-value/artistic

Or, in visual form:

The SCAN frame also helps to emphasise that the boundaries between the modes in the swamp are not clear-cut: the boundary between ‘truth’ versus ‘value’ will always wander with each throw of Einstein’s Dice, and the effective boundary between ‘outer’ versus ‘inner’ is as arbitrary as the point at which ‘time-before-decision’ changes to ‘Now’.

Note, though, that as time-before-decision is compressed down towards the Now, our choices in terms of the swamp become similarly constrained: if we can’t cope with Artist-mode uncertainty – as mastery of any skill will at some point always demand – then we’re all but forced into dependence on Belief. Which leaves us wide open to be preyed upon by any passing Priest – or any passing IT-salesman with their latest fad-fuelled ‘silver-bullet Solution’, which comes to much the same thing. Hence why all of this kind of exploration really does matter, folks…

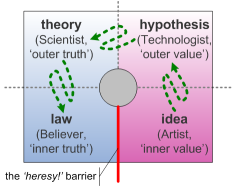

Idea, hypothesis, theory, law

The whole set, interestingly, also links well with the the ‘traditional’ concept of scientific development, from idea to hypothesis to theory to scientific ‘law‘:

There’s a certain amount of back-and-forth between the domains, but the overall progress of the cycle is clear. The catch, as can be seen from the diagram, is that it should be a continuous cycle, returning from ‘law’ to new ideas: yet all too often the metaphoric Priests cling to the new-found ‘law’ as a source of certainty, and build what they hope are impregnable walls against any return to the uncertainties of the Artist. The word ‘heresy’ literally means ‘to think differently’: in the larger scheme of things, the notion that ‘to think different’ should be considered a problem is almost laughably absurd – and yet no-one should doubt the intensity of emotion that fears of ‘heresy’ can invoke… Strange indeed.

Layers and recursion

Note that the labels here – Artist, Scientist, Technologist or Believer – are labels for sensemaking modes, or modes of thought: they’re not descriptions of people. In reality, although probably all of us have one or other mode that we would use as our ‘home-base’, most people will traverse through all of these modes at some point during the sensemaking/decision-making process. Each mode looks at the world in its own distinct way, with its own distinct notions of ‘success’ or ‘relevance’ or ‘proof’: they are different.

Yet the key point here – one that is absolutely essential to understand – is that none of these modes is considered inherently ’better’ or ‘truer’ than any of the others. The modes each have their own role to play, their own advantages and disadvantages, contexts where they work well, other contexts where they don’t, as we work through the whole process of mapping-out the overall context-space.

Among other implications, this immediately introduces the notion of recursive layering, where the model becomes both a model of reality and a model of itself looking at ways to make sense of reality. To get the best results in any context, for example, we might need to be able to move around within the conceptual space, use the different modes, like a Technologist; we might choose to stick with the Scientist’s platform for a while, or dig deeper into an idea as a Miner would, or brainstorm for new ideas like an Artist.

Layers within layers: the swamp metaphor.

Anyway, enough for now: comments / ideas / applications, anyone?