Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2013/12/14/definitions-on-capability/

This one’s really straightforward: it’s just a follow-up to a public request on Twitter by Bizzdesign consultant Bas van Gils:

- basvg: I am looking for definitions of these concepts, please help: capability, capability based planning, capability increment, capability map

I’ve no idea what any supposedly ‘official’ definitions might be, but these are the ones I use, based in part on work we did at Australia Post:

– Capability: the ability to do something.

– Capability-based planning: planning to do something, based on capabilities that already exist, and/or that will be added to the existing suite of capabilities; also, identifying the capabilities that would be needed to implement and execute a plan.

– Capability increment: an extension to an existing capability; also, a plan to extend a capability.

– Capability map: a visual and/or textual description of (usually) an organisation’s capabilities.

Yes, I do know that those definitions are terribly bland and generic – and they need to be that way. That’s the whole point: they need to be generic enough to be valid and usable at every possible level and in every possible context – otherwise we’ll introduce yet more confusion to something that’s often way too confused already.

Note what else is intentionally not in that definition of ‘capability‘:

- there’s no actual doing – it’s just an ability to do something, not the usage of that ability

- there’s no ‘how’ – we don’t assume anything about how that capability works, or what it’s made up of

- there’s no ‘why‘ – we don’t assume any particular purpose

- there’s no ‘who‘ – we don’t assume anything about who’s responsible for this capability, or where it sits in an organisational hierarchy or suchlike

We do need all of those items, of course, as we start to flesh out the details of how the capabilities would be implemented and used in real-world practice. But in the core-definition itself, we very carefully don’t – they must not be included in the definition itself.

The reason why we have to be so careful and pedantic about this is because the relationship between service, capability, function and the rest is inherently recursive and fractal: each of them contains all of the others, which in turn each contain all of the others, and so on almost to infinity. If we don’t use deliberately-generic definitions for all of those items, we get ourselves into a tangle very quickly indeed – as can be seen all too easily in the endless definitional-battles about the relationships between ‘business-function’ versus ‘business-process’ versus ‘business-service’ versus ‘business-capability’ and so on.

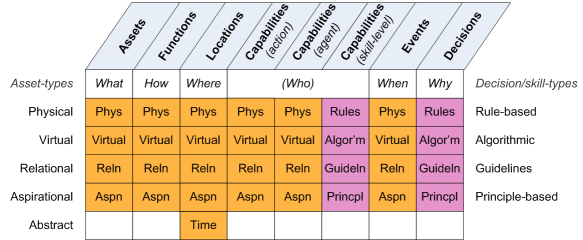

In principle there are many different ways in which we could sort out the relationships between definitions, but the one I’ve found simplest in practice – and the one I use in modelling with Enterprise Canvas – is to start from an assertion that everything is a service. This then gives us a set of relationships between assets, capabilities, functions and various other types of entities encapsulated ‘within’ each service, that we could represent visually as follows:

Note that ‘capability’ in the above diagram is split into three sub-components:

- action: what kind of ‘thing’ (or combinations of ‘things’) that the capability can act on

- agent: what kind of ‘thing’ does the ‘doing’ in the capability

- skill-level: in essence, the level of variation and uncertainty that the agent(s) and the overall capability can handle

Again, remember that all of this is recursive and fractal: capabilities are made up of services that are made up of all of the above, that in turn are made up of services that… well, you get the picture. ![]()

Another theme that I’ve explored in various posts – such as ‘Service, function and capability (again)‘ and ‘Service, function and capability (an addendum)‘ – is how capability, function and service actually fit together. To quote from the former of those two posts:

- everything in the enterprise is or represents or signifies a service

- a process links services together in some way to achieve some kind of outcome

- a function is an external view of a service – in effect, a description of its interfaces (‘black-box’ view), often together with a summary or overview of what it does and how it does it (‘white-box’ view)

- a capability is the ability to do something

- a function needs to be linked to a capability in order to do anything

- on its own, a capability literally has no function

- in a service-architecture, we link together a function and a capability (and various other service-content items, as in the diagram above) in order to create a service

Another way to summarise this difference is to describe it in terms of the structure of service-level agreements:

- the function describes the parameters of the service-level agreement – which should remain essentially the same for all implementations of the service

- the capability determines the parameter-values to be assigned to those parameters in the service-level agreement – which are likely to be different for each implementation of the service

The function is the outside view of the service; the capabilities deliver ‘the ability to do stuff’ that’s embedded inside the service. Which we could summarise visually as follows:

We can put together the functions (interfaces) and capabilities (‘ability to do something’) in all manner of different ways, providing us with options, for example, to deliver the same nominal service via different capability-agents (as in load-balancing, disaster-recovery and business-continuity) and/or with different skill-levels and competencies (as in customer-service escalation), all through the same function-interface. Or we could switch function-interfaces but use the same services and capabilities behind it (as in cross-platform service-delivery). The point here is that it can be extremely difficult to model all of these interchangeabilities and options for reconfigurations unless we do use flat definitions of this kind.

Given that definition of capability, then capability-based planning is about identifying what capabilities we have (or could have, or need), what we could do with those capabilities, and how we could put them together in different ways with different function-interfaces to deliver whatever services we need. Alternatively, we can run the whole thing the other way round: we would start from the overall need, then identify the services required to deliver that need, then the function-interfaces and service-delivery parameters for those services, and finally derive the capabilities needed within and behind the services – for which we’d then do a gap-analysis between the capabilities we have and the capabilities we need to find.

Which brings us to capability increment, because that’s what we’d need to build whenever there’s a shortfall between the capabilities we have and the capabilities we need.

In turn, that brings up to capability map, which is just a catalogue of capabilities, usually in accordance with some kind of structure or taxonomy (hence ‘map’). Note that if we’re going to be pedantic about it – which we probably should – we’d use the same definitions as above to distinguish between service-map, function-map and capability-map. The purpose of the capability-map is to help us identify what capabilities we have, what relationships we have between them (as per the taxonomy or structure behind the mapping itself), and probably where and under whose responsibility each capability resides – all of which, in turn, is going to be important for capability-based planning and the like.

I can throw in more comment and definitional-stuff if you need it, but I hope that makes enough sense for now? Over to you, anyway.