Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2013/12/29/avoid-delusions-of-strategy/

What is a strategy? How do we create a strategy? – rather than merely a delusion of ‘strategy’?

Several of the folks in my Twitterstream – Gerold Kathan and Shawn Callahan, amongst others – pointed recently to a great HBR post by Roger Martin, ‘The Big Lie of Strategic Planning‘. (Fortunately – and, these days, unusually – the article seems to be available outside of HBR’s bewretched registration-wall.) Read that article first, then come back here.

The first point here is that strategy is about working with inherent uncertainties.By contrast, planning inherently starts off with a stream of assumptions around a general theme that the future can be made certain – of which, usually, the first of those assumptions is that the future will be just like the past, only more so.

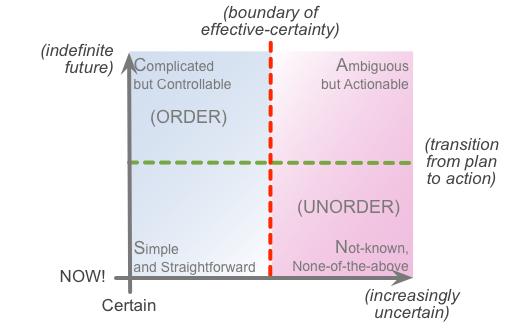

We can use the SCAN frame to summarise where things can easily go wrong in strategy-development:

In one sense, strategy and planning have some similarities, in that both take place at some distance away in time from the point of action: in SCAN terms, both are some way up from the base of the frame, though with strategy usually ‘higher’ (further from ‘now’) than planning. Yet strategy and planning are also very different: key parts of strategy will, by definition, be way over on the far-right of the frame, whereas most of planning focusses on the supposed ‘certainties’ of the far-left – or aim to get there, at any rate. If we mix these up in any way – treating strategy as as if it’s as ‘certain’ as planning, or planning as ‘uncertain’ as strategy, or either as the same as the ‘now’ of operations – then we’re going to be in trouble: big trouble…

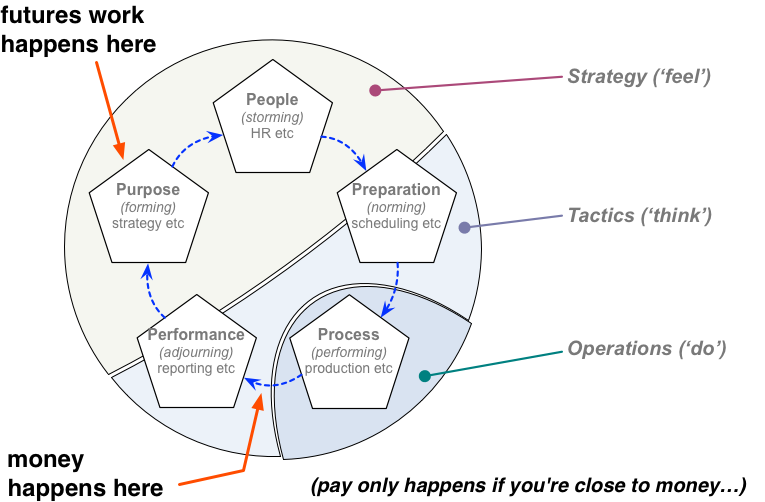

The next point – as Roger Martin makes clear in his article – strategy is more about feeling than thinking. It’s also much more about people than about plans. We can use the Five Element model to highlight those distinctions:

No-one doubts that serious thinking is required, in business and elsewhere, if plans are going to come to fruition. But that kind of thinking comes later in the Five Element cycle – and between the ‘feeling’-orientation of the Purpose phase, and the ‘thinking’-orientation of the Preparation or planning phase, that strategy has to pass through the gauntlet of the ‘storming’ that takes place in the People phase. That ‘storming’ phase – and indeed the exploration that comes before it – can often be very uncomfortable indeed, as Roger Martin warns in his article; but if we try to skip over that phase, the strategy will fail. There’s no viable way to avoid it: the only kind of comfortable, certain ‘strategy’ we can think our way into will be a delusion, based on circular-reasoning and the rest. Not a good idea…

The Five Elements model also warns us of another trap that can arise from mistaking ‘think’ for ‘feel’: the ‘quick-profit failure-cycle’:

Roger Martin does also warn about this trap, if in a rather different way, citing the short-termist pressures of the share-market, and managers’ natural aversion to discomfort and their propensity towards ‘control’. Either way, the tendency to over-focus on ‘thinking’, and on the supposed ‘certainties’ over on the left-side of the SCAN frame lead straight to a short-cut loop that slowly stifles trust, purpose, values, relationships with people, and even the policies that underpin the thinking itself – and, eventually, yet seemingly ‘without warning’, into a death-spiral from which recovery is unlikely at best. In other words, yet another ‘Not a good idea…’.

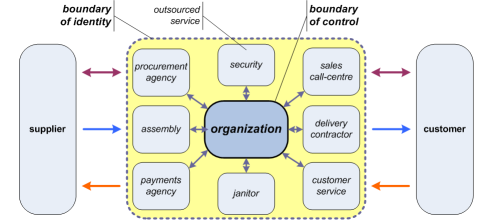

The next theme Roger Martin highlights in his article is that much of the context of strategy is inherently beyond the organisation’s control. In SCAN terms, ‘control’ is possible only on the far-left of the frame, and only where the organisation’s assumptions and fiat can hold – which, in practice, will only occur within the organisation itself. As Martin says, that proviso definitely does not apply to an organisation’s customers, even in context of a business-monopoly. Yet it also does not apply with outsourced services, which are ‘inside’ the organisation’s boundary of identity , but ‘outside’ of its boundary-of-control’:

An outsourcing-contract may specify deliverables that match up with the expectations of planning; but if the outsourced behaviours – beyond the organisation’s control – fail to match up to those required by the feel of the strategy, then it’s the organisation that will wear most of the damage.

There are all manner of critical issues here that need to be addressed: the nature of enterprise as a shared-story, for example, or the necessary linkage between vision, role, mission and goal. If the so-called ‘strategy’ is merely a glorified form of planning, most of those ‘beyond-control’ issues are likely to be missed.

Finally, Roger Martin alludes to the very real need, in strategy-development, to avoid an over-focus on money – a dangerous tendency in business anyway, but one that is easily exacerbated whenever planning is confused with strategy. The reality is that, in all cases, much more than just money is involved – as indicated by the value-flows in the Enterprise Canvas model:

Money comes into the picture almost only at the end of the Five Elements cycle, in the ‘Completions’ transition between Process and Performance: it’s an outcome of successful service-delivery, and – given all of the preceding inherent-uncertainties of very little use or meaning much before that. Attempting to use predictions about money as a guide for tactics – let alone as a guide for strategy – all but guarantees a suicidal dive into the short-cut short-termism of the quick-profit failure-cycle.

Strategy is, by definition, a form of futures-work, so we can also illustrate the same point in another annotation on the Five Elements cycle:

Which also illustrates why ‘performance’-oriented managers are well-placed to extract money for themselves from that point in the cycle, whereas strategists rather obviously aren’t…

Anyway, let’s summarise all of this with a quick set of checklists, drawn in part from Roger Martin’s article, but also from the deeper detail of the models referenced above:

– Warning-signs of risk of a delusional pseudo-strategy:

- Sense of predictable certainty about all aspects of the future as described by the strategy – or, conversely, absence of discomfort or uncertainty about the future

- Extension of the past directly into the future – such as the classic “Our strategy is last year +10%”

- Description of the strategy primarily or solely in quantitative form – in particular, a description primarily or solely in monetary form, with projected profit as a kind of ‘reverse budget’

- Use of expectation of monetary-return as a (or the) primary input to strategy – rather than as a description of desired output

- Expectations of ‘control’ or ‘possession’ of arbitrary themes within the market, or ‘market-share’

– Cross-checks for a viable strategy:

- Clear sense of meaningful story that links across all of the shared enterprise (ideally expressed as a single phrase or sentence)

- Clear sense of the organisation’s place and role within that story

- Clear sense of the organisation’s qualitative promise and commitments to other actors within that role and story – including a clear sense of how the organisation will ensure that it keeps to those commitments

- Clear sense of the organisation’s relationships with all other actors in the shared-enterprise, as indicated by the strategy – and of the balances and cross-checks between each of those relationships

– Cross-checks for an actionable strategy:

- Clear description of how the strategic-story (Purpose) would connect with the enterprise-actors (People), then lead to appropriate tactics (Preparation), operations (Process) and identifiable outcomes (Performance), and thence link back both to the initial strategy and to inform future strategy

- Clarity on how the strategy would impact on relations with enterprise-actors

- Clarity on how existing and/or new capabilities would be used and/or required, to action the strategy

- Clarity on principles and values that could be used to support appropriate decision-making, in line with the ‘promise’ of the strategy, in any contexts of uncertainty at the point-of-action

- Clarity on what would or would not be considered a ‘good’ outcome in terms of the strategy, and how to identify such outcomes

- Clarity on how the strategy supports revision of itself – i.e. ‘emergent strategy‘ – in line with the overall enterprise-story, of which the strategy is itself just one possible expression

Enough for now, but I hope that provides a useful addendum to Roger Martin’s article?

Comments, anyone?