Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2015/06/18/john-zachman-at-bcs/

A couple evenings ago the BCS (British Computer Society) held a open question-and-answer session with John Zachman at the EAC-BPM conference in London. How much has the Zachman Framework for enterprise-architecture changed over the past decades – and particularly over the past few years?

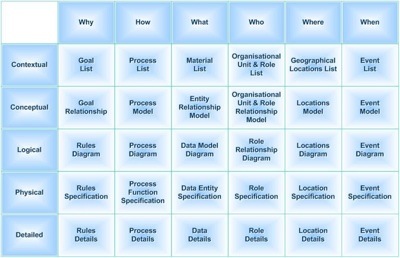

If you don’t know the Zachman framework already, here’s a quick visual summary:

In effect, it’s a list, or taxonomy, or ontology, or categorisation, of what Zachman calls ‘primitives’ for enterprise-architecture, laid out in a 6×6 or (as here) 5×6 matrix: a six-column horizontal-axis of ‘Why’, ‘How’, ‘What’, ‘Who’, ‘Where’ and ‘When’ (though in no particular order), and a five- or six-row vertical-axis from most-abstract (or most-’architectural’) to most-concrete (detail-layer implementations).

The layout has changed back and forth over the years – as can be seen in some detail on the respective Wikipedia page – but the core idea has remained much the same since its first inception back in 1987. In the BCS session, Zachman took us another couple of decades further back, to a bunch of folks at IBM struggling to provide appropriate data-systems support for a huge oil-company merger in the late 1960s onwards.

There’s no doubt at all that the Zachman Framework has been hugely influential – in part because of its simplicity, but in no small part because Zachman himself is unfailingly one of the nicest people we could ever hope to meet. Given that, it does kinda hurt to have to say that, in reality, the framework is a real curate’s egg – ”excellent in parts, m’lord”:

Bishop: ‘I’m afraid you’ve got a bad egg, Mr Jones’

Curate: ‘Oh, no, my Lord, I assure you that parts of it are excellent!’

Unlike the original curate’s-egg, yes, there are some definite good-points, with real value – but also some serious howlers, and all underpinned by a metaphor that’s so fundamentally wrong that it’s crippled enterprise-architecture for decades. Yeah, really, that bad… ouch…

To explain why, it’s probably simplest to use some of the quotes from the session.

First, though, a trio of quotes that indicate the character of the man himself:

– (on learning anew) “I’ve learned more about enterprise-architecture in the last five years than in the previous twenty-five.”

It would have been so easy to have stopped with the original framework, capitalised on its huge popularity, and left it at that. Instead, Zachman has had the humility and courage to keep questioning himself, to keep learning; too many others don’t.

– (on use of frameworks) “Please explain to me the business-problem you’re trying to solve, and how you plan to solve it.”

This is the right way to do it: the business-question comes first, not the framework. Far too many people get this one the wrong way round; Zachman doesn’t.

– (on attempts to possess the framework) “Early on, one of the tool-vendors wanted me to sell them the framework as an exclusive, so that they could claim to own enterprise-architecture. That’s wrong: the framework is a fact of nature – it can’t be owned. I do not believe anyone owns the Periodic Table, or the Zachman Framework.”

I’d definitely sing Zachman’s praises here, because he could have got a lot of money for indulging in that all-too-common form of dishonesty. Instead, he’s aligned himself with the other, responsibility-based form of ownership, and acted as a steward of the framework, protecting it as itself on behalf of everyone. Yes, he’s made a good living out of doing so over the decades – but also worked darn hard for it, too, when the dishonest sell-out would have been so much easier. That choice shows real strength of character, real honest steel behind the surface – something well worthy of respect.

Yet this is where things get difficult…

That’s because whilst Zachman himself is a quiet giant in his own way, the framework itself – and even more, its historical and conceptual underpinning – is deeply, deeply flawed, to the extent that it’s often dangerously misleading: a curate’s-egg, arguably “excellent in parts, m’lord”, but so pervaded by subtle rottenness that we might be wise to discard the whole thing and start again. And yeah, I’m well aware that that interpretation could be kinda unpopular, so it’s perhaps best illustrated too by various quotes from the session.

– (on the core basis for architecture) “data, control, infrastructure, systems, planning”

This was a reference back to the ‘Data Processing’ of the late-1960s, but it’s clear that it still holds for his thinking even today. Anyone notice what’s missing from that list? – yep, people. In fact he made it clear that the whole idea was to remove people from any consideration – replace people with automation in every possible way. In other words, classic Taylorism – with all of the errors and failings that that implies.

– (also on core concerns for architecture) “The secret to this whole thing is the categorisation of the data.”

No, it’s not: that’s confusing information about a ‘thing’ with the ‘thing’ itself, often recursively. It’s a classic ontology-error that seems to be endemic among IT-folks, but it does need to be understood and challenged as an error, wherever it may occur. This one error permeates all of the thinking behind the Zachman framework – and is one of the core reasons why the framework is so problematic in real-world practice.

– (on the scope of architecture) “It’s not an IT issue.”

No, it’s not – very much not. (Or not solely an IT-issue, anyway – because no question at all that IT would always be relevant somewhere. Just not the central issue – a too-subtle distinction for some people, it seems, yet utterly crucial.) The catch is that every example that Zachman gives is ultimately an IT-based example – such as that in the ‘What’ column, after ‘Material List’ the only ‘What’ mentioned is data. What about physical things as ‘What’? relations? brands? – don’t they exist? – don’t they matter too? Apparently not…

– (on limits of scope for EA) “He did not think anything with less than $500M (1970) revenue was worth doing architecture for.”

To be blunt, that’s stupid (though we should note that Zachman’s quoting someone else here). There’s perhaps a crucial distinction here between the scope of what IBM would believe worthwhile to sell EA-services for – which, yes, could well be that size and scale – versus the actual limits of need – which are much, much smaller, and seem to apply to organisations of every size, large and small. I’ve worked for larger-sized organisations too – 100,000 person was probably the largest so far – but in practice I’ve also worked with other organisations all the way down to a 30-person small restaurant-chain, a 20-person primary-school and even a 2-person (but very-high-’value’) investment-team. Others in whole-enterprise EA have said much the same. From a discussion with Philip Hellyer at the conference, it seems likely that whilst EA would be useful and valuable even for a two-person startup, some form of EA becomes all but essential as a guide for communication and integration once an organisation, as a sociotechnical-system, expands in size much beyond the Dunbar Number – around 150 people or so. IT-complexities tend to become critical at somewhat larger organisation-size – particularly after merger/acquisition or major market-change – but as Zachman says above, “It’s not an IT-issue”: the real concerns for EA are about communication between people first, not just machines.

– (on his concept of ‘primitives’ and ‘composites’) “The primitives are the architecture.”

No, they’re not – they’re an aid to architecture, not the architecture itself. As he himself said later, “implementation has to be a composite”: the architecture is in the interaction and interplay between primitives and composites – not just one or the other. That’s a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature and practice of architecture there that is, again, deeply embedded in the framework. Oops…

– (on the role of IT in the enterprise) “We, the IT people, have been driving the enterprise for 70 years – the [IT]-system is the enterprise.”

No, no, no: this is fundamentally wrong – IT-centrism at its worst. IT is, yes, has been and will no doubt continue to be a key enabler for key aspects of the enterprise – no-one doubts that at all. But an enterprise itself is, literally, “a bold endeavour” – and IT-boxes, in themselves, are neither bold, nor do they endeavour. To say that “The [IT]-system is the enterprise” is, by definition, to confuse means with ends – Not A Good Idea… Instead, always, always, the core of the enterprise is people: if we ever get that point wrong, our ‘enterprise’-architecture will likely be worse than useless, a mere distraction from the real concerns of the enterprise. Again, this is yet another fundamental error that is embedded and expressed throughout the framework and most of its popular usages.

– (a question from the audience – from Elizabeth Erwin, I think?) “IT has hijacked EA: how do we get people to understand that rows 1-3 are about business, and just as important as row 4-6 implementation?”

We didn’t get an answer on that from Zachman himself, though we did get a few from the wider audience. The blunt reality is that this is yet another core failing of the framework, arising in part from the muddled concept of ‘primitives’ versus ‘composites’. For what it’s worth, I’ve spent a lot of work over the past several years on this, at first for the whole-of-enterprise rework for the TOGAF ADM (see e.g. ‘Spot the difference‘), but also as a core aspect of Enterprise Canvas – see the posts ‘Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 4: Layers‘ and ‘Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 5: Service-content‘.

– (about the ‘science’ of EA) “When Mendeleev published the Periodic Table, the alchemists were very unhappy.”

Okay, I’ll admit this is a bit of a hobbyhorse of mine – perhaps not so directly related to EA as such? – but I do get annoyed when I see poor grasp of both science and history portrayed as ‘fact’. As a discipline, alchemy had largely died out at least a century before Mendeleev – hence no alchemists to be “unhappy” – though it was popular in previous centuries, even amongst such pillars of science as Isaac Newton. Mendeleev’s achievement was to codify already-existing knowledge, in a way that pointed towards new possibilities: so yes, in that sense, the same sort of idea could be claimed for Zachman’s framework, though not really in the same sense. The big problem, though, is that there are very real limits as to how much mainstream ‘science’ can apply in the sociotechnical-systems in the EA context – see, for example, the post ‘Theory and metatheory in enterprise-architecture‘. And there are also strong grounds to suggest that there’s much that we could still learn from alchemy, too – see the post ‘Enterprise-architect – applied-scientist, or alchemist?‘. In short, don’t be quite so quick to disparage others in the past, as a cheap way to make a present-day idea look better than it actually is – lest others in the future disparage our work in the same way too.

– (on the basis for enterprise-architecture) “Architecture for airplanes, ships, chairs, buildings, it’s all the same – why should it be any different for enterprises?”

This is the howler, the clanger, the one really, really fundamental error that not only cripples the Zachman Framework, but because the framework has been so popular, has also crippled enterprise-architecture itself for way too many decades now. The short-answer to his question is that yes, enterprises are different – fundamentally different – from “airplanes, ships, chairs, buildings”: the latter represent physical ‘things‘ (or virtual ‘things’, if we extend it to data-architecture and the like), whereas an enterprise is a sociotechnical-system, comprised of people as much if not more than of any kind of ‘thing’. Zachman’s metaphor of ‘engineering the enterprise’ could perhaps sort-of work well enough for the solely ‘-technical’ aspects of a sociotechnical-system, but not for the human or ‘socio-’ aspects of a sociotechnical-system – and the whole point of a sociotechnical-system is that the two types of elements are inherently interwoven with each other.

We do not, cannot and should not attempt to ‘engineer’ people and people’s behaviour, because it doesn’t work – not in the same way as machines, anyway. That was the Taylorist fallacy, that’s been proved false time and time again, in often-disastrous mistakes such as IT-driven ‘business-process reengineering‘. The one-line summary here: enterprises are not technical-systems but sociotechnical-systems – hence the concept of ‘engineering the enterprise’ should never be used as a metaphor for enterprise-architecture.

In short, the Zachman Framework is a ‘curate’s-egg’: it looks good on the surface, but is deeply-flawed, in many different ways – flaws that have been embedded in the framework right from the start, and yet have not been properly addressed at all in the three decades or so since then. Useful though it is in enterprise-architectures, the framework can be dangerously misleading if not used with care, capable of causing very real damage to the respective organisations – and we ignore its flaws at our peril.

Yet another You Have Been Warned item, perhaps?