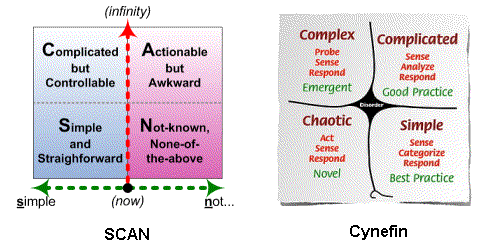

Sensemaking in business? What is this [choose-your-expletive] ‘SCAN‘? Why complicate things with yet another sensemaking-framework? Isn’t SCAN just a rebadged rip-off of Cynefin? And why not just use Cynefin like everyone else does, anyway?

I’ll be providing some detailed worked-examples of SCAN in the next few posts or so, but I’d better get these questions out of the way first, because otherwise someone or other will jump at me about it if I don’t. The quick answer is, yes, there are solid reasons for all of this, and no, this isn’t ‘having a go’ at Cynefin or anything else. Okay?

To answer each of those above questions in turn:

- making sense – and making sense fast – of things that don’t yet make sense, is an essential business requirement, in enterprise-architecture and in just about every other business-discipline

- what we often need for business-sensemaking is something simple, fast, and easily memorable, yet also has all the sensemaking depth behind it – and SCAN supports that need

- the aim is to simplify, not complicate – the main reason for SCAN is to uncomplicate something that’s become almost hopelessly complicated and problematic

- the two frameworks may look similar on the surface, and I’ve intentionally designed SCAN so that they can be used in parallel, but they actually have significantly different roots, roles and methods

- in practice, in most of the business-domains I work in, usage of Cynefin seems a bit like TOGAF for enterprise-architecture – just about everyone says they use it, but almost no-one actually seems to use it as per the published specification

That last point has lead to lots and lots and lots of fights over the past few years: too many fights, between too many people, in which I’ve too often found myself in the painful position of pig-in-the-middle… So in the hope that it’ll defuse some of the drivers for at least some of those fights, what I’m aiming to do here is:

- separate out two fundamentally different types of sensemaking – ‘considered’, versus ‘business-speed’

- explicitly acknowledge that Cynefin fits well with the needs of ‘considered’ sensemaking

- describe how and why Cynefin has proven problematic in ‘business-speed’ sensemaking

- how SCAN sets out to resolve each of those issues, specifically for ‘business-speed’ sensemaking

There’s some overlap between SCAN and Cynefin, obviously, because both are tools for general-purpose sensemaking; but the key point is that they serve and emphasise different business needs.

Business roles

Making sense, to support good decision-making, is an obvious business need.

In practice, there are two fundamentally-different kinds of business sensemaking:

- ‘considered’ – analysis and experimentation, classically done by consultants, professionals, senior management and strategy staff

- ‘business-speed’ – categories, checklists and personal judgement, classically done by line-managers, supervisors and front-line staff

The crucial distinction is available time. If we had the time at the front-line to make a proper ‘considered’ assessment and decision, we’d do so: but we rarely have that luxury. So at ‘business-speed’ we have to make do with a different kind of sensemaking: it’s not as pretty, not as precise, not as ‘scientific’, but it’s pragmatic and practical. Simply what works, at the time, in the time available.

In other words, both kinds of sensemaking are ‘true’, for a given value of ‘true’. The practical question is about which kind is more appropriate – more useful – for a given business need.

Cynefin explicitly positions itself for ‘considered’ sensemaking. To use the Cynefin terms, it emphasises the Complicated and, especially, the Complex domain. I believe it’s fair to say that it aims to elicit insight and understanding by focussing on nuance and subtlety, on emergence in complex adaptive systems, and so on. We do get the most ‘scientific’ results this way: but it takes time.

SCAN explicitly positions itself for ‘business-speed’ sensemaking. To use the Cynefin terms, it emphasises the interplay between the Simple and Chaotic domains. It uses classically simple-yet-powerful techniques such as recursive checklists, to access the full depth of sensemaking whilst still maintaining full business-speed.

In short, the frameworks’ roles and emphases are not the same: as above, they’re both about sensemaking, but they service somewhat different business needs.

Framework roots

Cynefin’s roots go back to at least 1999, and are primarily in the sciences. As its Wikipedia page puts it, “the Cynefin framework draws on research into complex adaptive systems theory, cognitive science, anthropology and narrative patterns, as well as evolutionary psychology”.

SCAN’s roots go back to at least 1986 (the ‘swamp analogy‘ for sensemaking), and are primarily in pragmatics. There’s a lot of science and more behind it – for example, on Jungian psychology and the tetradian, cognitive psychology, textual deconstruction, real-time learning and real-time decision-making – but the focus is always on real-world practice.

In other words, one has a science focus, the other a technology focus. It doesn’t make much sense to try to assess either one solely in the other’s terms.

Practical problems with Cynefin

This section describes some practical problems that I and others have often come across whilst trying to use Cynefin with everyday business-folk in enterprise-architecture and the like – in other words, primarily in contexts that demand ‘business-speed’ sensemaking. I’ll also describe how SCAN addresses and, I hope, mostly resolves each of those problems.

I know it sounds petty, but often the first hurdle is just the name ‘Cynefin’. Even the pronunciation is problematic: I’ve come across several people who’ve talked excitedly about ‘sign-fin’ – which is how standard-English would (attempt to) pronounce ‘cynefin’ – and get very confused when someone else uses the proper Welsh-style pronunciation ‘kuhnevin’.

[It’s not that the Welsh pronunciation is ‘wrong’, because obviously it isn’t. It’s just that it confuses people, and gives an unfortunate impression of an ‘in-group’ who know how to pronounce it properly, versus an ‘everyone-else’ who don’t.]

By contrast, SCAN is pronounced exactly as per the standard-English spelling.

We’ve had similar problems around the meaning of ‘Cynefin’. The Wikipedia page explains it as follows:

Cynefin is a Welsh word, which is commonly translated into English as ‘habitat’ or ‘place’, although this fails to convey its full meaning. A more complete translation of the word would be that it conveys the sense that we all have multiple pasts of which we can only be partly aware: cultural, religious, geographic, tribal etc.

In practice, with front-line managers, I’ve possibly lost them at the first word, probably lost them at ‘Welsh’, and definitely lost them by the time we bring ‘habitat’ or ‘place’ into the picture – let alone ‘multiple pasts’ or anything else. I then have to do quite a long explanation as to how and why, yes, this is about business-sensemaking, and it’s useful and important. That’s if they allow me any time to do it, which often they don’t… which doesn’t help.

[Again, this is purely pragmatics: the richness and depth of the word ‘cynefin’ is indeed valuable, yet the lack of self-description in the name makes it that much harder to get started.]

By contrast, SCAN says straight away what it is and does: we do a scan through the context to make sense of what’s going on.

Cynefin also depends on special meanings of common terms. The worst problems have been around ‘complex‘: Cynefin uses this in the specific sense as in complexity-science, but that’s landed us with huge arguments with IT-folks and others who’ve always used ‘complex’ to mean ‘very complicated’. We’ve had similar arguments around ‘complicated‘ itself; and likewise ‘chaos‘, which Cynefin uses in an uncommon way, quite different from the colloquial usage. Even ‘simple‘ has turned to be not as simple as we’d thought.

[Once again, this is purely about pragmatics: those special-meanings in Cynefin do enable much more precision, but at a significant cost in understandability and versatility, especially at ‘business-speed’.]

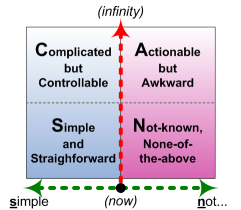

By contrast, SCAN provides suggested, colloquial terms for what are essentially similar sensemaking-domains to those in Cynefin, but beyond that it leaves terminology intentionally open. Surfacing personal interpretations of terms thus itself becomes part of the sensemaking process.

In my experience, perhaps the most serious problem has been that Cynefin presents way too much scope for methodological confusion – and especially so when people try to use it for sensemaking at ‘business-speed’, where everything will be pared down to the bone, whether we like it or not. The most obvious of these confusions is that it looks like a straightforward two-axis matrix – which it isn’t. Visually, it’s presented as a categorisation-framework – which it isn’t. (Or is. Or isn’t.) There are those four straightforward domain-categories that everyone sees – the SCCC-categorisation of Simple, Complicated, Complex and Chaotic – but then there’s the fifth-domain of Disorder – which is both a domain in its own right and the backplane for everything else – and the ‘squiggle’ – which frankly takes too much effort to explain.

Then there are all the Cynefin methods behind it, which in principle are grounded in complexity-science and so on, but often don’t match up with how most people understand ‘complexity’ in just about any discipline other than complexity-science. In sensemaking at business-speed, we simply don’t have time to do that kind of translation between disciplines – hence no surprise that key nuances get lost in the non-translation. And the general opacity and special-meaning-after-special-meaning of the methods mean that there are – as I and far too many others have discovered the hard way – all too many options for ‘illegitimate’ usage of Cynefin, and not many ‘politically-correct’ usages that actually do make practical sense in our work-domains. So in practice we end up saying, yes, it’s a sort-of four-category framework that isn’t, sort-of, that’s why it has those pretty curved boundaries, sort-of – and then just kind of hope for the best, hiding behind cautious phrases such as ‘inspired by Cynefin‘ and suchlike. Which is not a good way to use anything.

Sure, Cynefin’s terminology is wonderfully precise, and likewise its methods: in skilled hands, and given enough time, it really can work wonders. But in practice, all too often, it’s been a bit like letting business-folk loose on a typical EA toolset: it’s so dependent on everything being done exactly right, that it doesn’t take long for the whole thing to turn into an impenetrable tangle of misunderstandings and confusion – the exact opposite of what we’re aiming for in business-sensemaking. And for ‘business-speed’ sensemaking, we simply don’t have time to sort out that kind of mess.

[A reminder again that I’m not saying Cynefin is ‘wrong’ – because clearly it isn’t. All I’m saying is that these are the kinds of methodological problems that I’ve seen arising time after time, in real-world practice, in enterprise-architecture and the like.]

By contrast, SCAN is bald and straightforward: it makes no pretence of being more than a simple cluster of four categories, arising from a plain ordinary two-axis matrix – and if we want to, it can be used, and useful, just like that, with nothing else. (In fact it can even be used as a single-axis ‘matrix’ – the tension between Simple and Not-simple, known and not-known.) It can, however, also go a lot deeper than that – yet all still with the same set of categories, all of the way.

A bit more detail on SCAN

The real power of SCAN comes not from the frame itself, but from what happens when we use that frame in conjunction with an equally straightforward set of systems-thinking principles. We can use those principles to any extent and any depth that we need – including none at all.

To use that usefully-precise Cynefin terminology, we could split those principles as follows:

- Simple: repetitive rotation between multiple views or perspectives or focus-themes – such as in a checklist or, here, a simple four-category frame

- Complicated: reciprocation – balance across a system – and resonance – the ‘snowball effect’ (positive-resonance) and damping (negative-resonance)

- Complex: recursion – self-similarity at different levels – and reflexion – patterns, particularly ‘the whole contained within the part’

- Chaotic: cognitive-dissonance – deliberate-mismatch to trigger ideas – and serendipity – allowing ideas to arise in unexpected ways

In terminology that might be more familiar for enterprise-architecture folk, this is about iteration and allowing emergence of new ideas and requirements, much as in any of the Agile development methods. It’s done at real-world speed, not ‘sit-and-think-about-it’ analysis-paralysis; there’s an explicit architecture to it, but it’s not the old Waterfall-architecture of ‘big-requirements-up-front’. It’s kept as simple as possible, but it’s not simplistic: there’s real depth behind it, whenever we need.

What we’re after – one of our key success-criteria – is when someone says, “Oh, I hadn’t thought of it that way…”, and then develops the whole discussion in a new and different direction. In other words, useful insights, arriving ‘from nowhere’, at business-speed.

In essence, SCAN is a ‘stealth’ form of context-space mapping. For simplicity, it’s constrained to a single type of base-map, but we can still apply any other overlay – including the Cynefin frame – to use as a cross-map in conjunction with any or all of those systems-thinking principles above. So it’s simple enough, and familiar enough, not to scare people off: yet we can go down into whatever depth we desire – or dare – in whatever little time as there may be available to do it.

Different trade-offs, different roles

To me, as a practitioner, I’d guess that the key difference between Cynefin and SCAN is that they make different trade-offs between precision versus flexibility, sophistication versus simplicity, and several other suchlike themes. Perhaps the best way to illustrate this difference would be the comment of an old friend of mine, who said that his greatest challenge as a mathematician working in aircraft-design was to make his mathematics sufficiently imprecise to be useful.

Another anecdote comes to mind here, a conversation some years ago in Lisbon. One of the people there was passionately holding forth about the inadequacies of English as a language: “We should all be speaking French!”, he exclaimed. “French is the language of diplomats! It is exact; it is precise.”

“The advantage of French is that it’s precise”, was the quiet reply. “The advantage of English is that it isn’t.”

Cynefin’s advantage is that it’s precise, a science-based ‘language’ appropriate for the needs of complexity-consultants engaged in ‘considered’ sensemaking.

SCAN’s advantage is that, by intent and design, it isn’t precise – which makes it a better fit for the more pragmatic needs of ‘business-speed’ sensemaking.

Different trade-offs, different roles.

Different choices.

But probably important that we don’t mix them up?

Over to you for comments and suchlike, anyway.