What happens when the simple definitions of Simple and Complex become complex? Do they become so Complicated that they can collapse into the Chaotic? And if so, what can we do about it?

This one’s triggered in part by a swathe of complaints from various enterprise-architecture folks about a certain ‘standard definition’ of Complex, and also in part by a double-Tweet by Bruce Waltuck:

- complexified: @tetradian @davegray @Jabaldaia the 1st challenge is to understand the difference between complicated & complex. // 2d, understand different patterns of inquiry & response in each domain (complicated vs complex)

Sounds straightforward, doesn’t it? – define some differences, define the differences of methods that apply in each case, do it, all done. Easy: no sweat!

The reality ain’t quite that simple, though…

[…as I know Bruce knows well, of course – hence ‘understand’, not ‘define’, in that Tweet above.]

To see why it ain’t so straightforward, let’s first take the usual definitions from what, for safety’s sake, we’d best call ‘the SCCC-categorisation‘:

– Simple: rule-based, predictable, direct cause/effect relationships; use categories to guide response

– Complicated: rule-based and ultimately predictable but often indirect cause/effect relationships, sometimes with feedback-loops; use analysis and algorithms to guide response

– Complex: meaning emerges from and interacts with context, ’cause/effect’ can be misleading; use patterns, guidelines and ‘seeding’ to guide response

– Chaotic: ‘anything goes’, no discernable ’cause’ or ‘effect’; use action to break out to another domain (usually Simple or Complex)

Yet in reality, judging from some of those complaints, what we actually have is something more like this:

I don’t find rules simple at all, to me they’re crazily complicated, or more like what you’re calling complex. To me, guidelines are much simpler to work with. And what’s the difference between ‘complicated’ and ‘complex’? – complex is just complicated that we haven’t yet worked out how to control, isn’t it? My whole job is about getting rid of complexity, and here you say it’s something we want? – that’s daft! And the service-management guys, all their work is about working with the chaos, not running away from it, so your definition don’t make no sense there neither.

Yeah, my head hurts too, trying to make sense of that… but it gets worse for a while yet… sorry…

What’s going on is that, to use those definitions above, definitions are a Simple tactic imposed on top of a Complex context, resulting in the would-be Simple becoming so Complicated with exceptions and uncertainties that it risks ending up as Chaotic. So to make it Simple, we have to accept that the Simple here is in fact Complex, and hence provide Simple rules to support a Complex anchor that allows for an emergent definition that is experienced as Simple by all those involved in that Complex social context. We avoid it becoming becoming too Complicated by accepting that it is Complex; and we use the uncertainty of the Chaotic to provide the source-experiences that ultimately make it Simple.

Simple, yes? ![]()

Uh, no…?

Okay, so let’s do a quick SCAN on this?

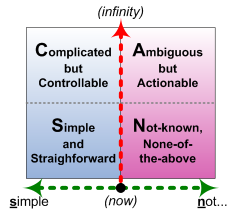

As a reminder, here’s the SCAN core-graphic again:

And the Inverse-Einstein test, which determines where we ‘are’ on the horizontal axis:

- if we do the same thing and get the same results, we’re ‘in control’ (whatever that means in the context) – which places us on the left-hand side of the graphic

- if we do the same thing and get different results, we’re not ‘in control’ – which places us on the right-hand side

A reminder, too, that the vertical axis is about ‘time until decision’: the less time we have, the more we’re forced either to a Simple form of ‘control’, or to work with the ‘Not-known’ as it is.

So: a SCAN on definitions and suchlike.

Definitions are good. They are – or should be – Simple, straightforward tools that allow us to make sense and make decisions at high speed.

The catch is that every definition is a Simple abstraction from what happens in the real-world. We choose to define it this way, to support this purpose. It’s true-for-a-given-for-a-given-value-of-’true’, so to speak: one person’s subjective-truth, used ‘as if’ it’s ‘objective-truth’ – which it isn’t. And it’s important we don’t forget that fact…

Definitions may be Simple and unambiguous for each person, for use in one specific context; but they’re highly Ambiguous between different people, and different contexts. So they’re both Simple and Ambiguous – all at the same time.

If we try to use a definition as if it’s only Simple – applies to everyone, everywhere, for everything – and we try to use it for control at business-speed, what we’ll get is lots and lots of arguments, about whose definition is the right one for the context. In other words, by ignoring the Ambiguous, it suddenly gets very Complicated – and thence, when people don’t know which definition is ‘the correct one’, but don’t have time to work things out, a collapse down into ‘Not-known’. Otherwise known as the wrong side of chaos…

So we speed things up by acknowledging the Ambiguity. We ask people what they each understand and use as their ‘the definition’ for that context. If there’s time available, we make a point of exploring those definitions in an explicitly Ambiguous form, to entice a collective definition to emerge from those differences. If we don’t have time to do that, we can impose a definition and still respect the Ambiguity by contextualising the definition, such as “For this purpose, we assert that the definition of… is…” – acknowledging that other definitions are possible, but this is the one that we’ll use.

We treat that definition as part of a Simple checklist, a ‘rule’: we can say “Do it this way, because we know that it works if we do it this way”. And we couple that later with another Simple check such as an After Action Review to verify that it actually does give the same results – the Inverse-Einstein test – and, if not, decide what to do about it. In other words, Simple tactics that work with the Ambiguous, rather than trying to pretend that it doesn’t exist.

Or, in the SCCC terms, a Simple way to deal with the fact that the Simple isn’t Simple. ![]()

So to make sense of the Complicated versus the Complex (in SCCC terms again), the first thing we need to do is acknowledge that the definitions aren’t as Simple as they might seem. Once we’ve addressed that, we then have a chance to develop a shared understanding of what each might mean in practice, and how to use that shared-understanding to support decision-making.

Just a quick SCAN there, anyway, to explore something that’s turned out to be surprisingly important in practice.

Hope it’s been useful: let me know, perhaps?