Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2015/05/28/effective-about-effectiveness/

Keep it simple.

Simple, yet not simplistic.

Acknowledge the complexity, yet don’t ever push that complexity in people’s faces. (Not until they’re ready for it and choose to face it, anyway.)

Help people find their own effectiveness about creating effectiveness.

That’s the real core to enterprise-effectiveness.

So let’s apply some of those principles of effectiveness to enterprise-effectiveness itself.

Keep it simple, without being simplistic.

Let’s start with one obvious point that’s been the focus of too many arguments: what is ‘the enterprise’?

If we strip that right down to its basics, what we get to is its literal meaning, of ‘enterprise’ as ‘a bold endeavour’. There’s nothing there that requires an enterprise to be a commercial venture, or a business, or particularly risky: it’s just some kind of endeavour that’s sort of bold in the sense that it has some kind of challenge in it. That’s about it, really.

Or, in short, ‘the enterprise’ is whatever we choose to say that it is.

Simple.

Yet which also means that we need to say what bounds we’ve chosen – because otherwise no-one else will know.

Kinda obvious when we put it like that. But far too often forgotten…

Let’s link that to another theme, that in working on ‘an enterprise as system’, everywhere and nowhere is ‘the centre’ of that system, all at the same time. In effect, ‘the centre of attention’ is wherever we say that it is – as long as we remember that everywhere else in the enterprise will also be ‘the centre’ at some point too.

Which means that perspective kinda matters here. And for, I use a simple structure of ‘inside-in, inside-out, outside-in, outside-out‘:

Inside-in is whatever we’re working on at the moment, our current ‘the centre’. We’re looking at it in terms of itself. We’ll probably focus most on efficiency and reliability – doing its job with the minimum of waste and fuss.

Inside-out is about making use of what it is that this does. Again, we’re likely to focus on efficiency and reliability, but often only from our own view of the world, the enterprise, the story.

To make it work – make it useful, make it part of a broader enterprise – we need to connect across to and with the ‘outside-world’, itself kinda looking ‘inward’ at our part of the enterprise-story. Here, we’re likely to focus more on appropriateness and what we might call elegance – connecting with people, in ways that do with the shared-story.

And then there’s the shared-story itself, in its own terms, that in effect defines what the enterprise is – what we might describe as ‘outside-out’. To connect with that, we’d focus again on appropriateness, but also even more on integration, how everything links together to support that overall ‘bold endeavour’ of the shared-enterprise.

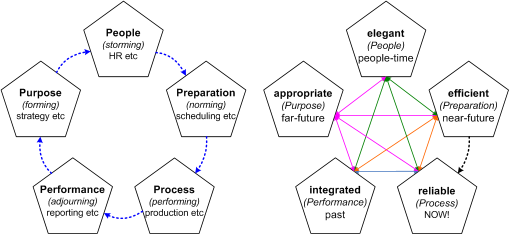

And we can link all of this together through simple frames – simple visual-checklists – that help us to keep our attention moving around throughout each of those contexts. These can remind us, for example, to focus alternately on themes such as leadership, phases of activity, the tasks to be done in those phases, different time-perspectives, and, yes, those themes of effectiveness, all interweaving with and interdependent on each other:

Yet enterprise – being enterprising – is also first and foremost about people, working together within and towards a shared-story.

Which means that we need to explore and engage with the stakeholders in that story.

Of whom there can be a lot more than we might expect…

To build effectiveness about this aspect of enterprise, let’s go back to that set of perspectives again, and look at them in another way.

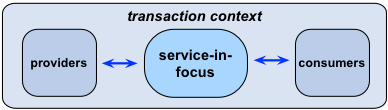

In general, I prefer to use a service-oriented approach to most architecture-type work, so I’d suggest reframing our ‘Inside-In’ – our current area of attention within the overall enterprise – as ‘the service-in-focus‘:

Some might describe this as a ‘White-Box’ view – we want to know the practical, internal details of how the service works. The stakeholders here are all the ‘usual suspects’ that we’d pick up from the org-chart, work-rosters and so on. Again, we’d probably focus most on efficiency and reliability, but also with an explicit awareness of the people-aspects – which means that we’d need to include some emphasis on elegance and appropriateness, the whole story that engages people in getting this service to work in the most effective way that we can.

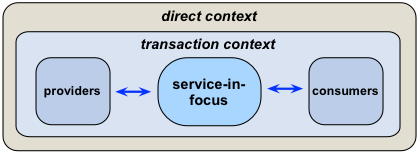

We then move to the ‘Inside-Out’ perspective, the various points of contact with others from outside the service – the parts of the context for our service within which transactions take place:

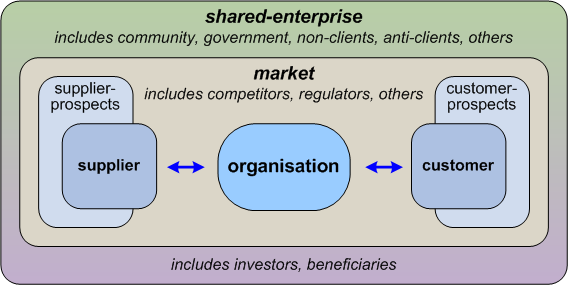

We might describe this as a ‘Black-Box’ view of the service, its APIs, its contracts, its touchpoints and the like – but ideally without needing any detail about the internal workings of the service itself. The stakeholders here are those of the service itself, together with all of the people who do or guide transactions: customers, suppliers, prospective customers and suppliers, and anyone else with whom the service would share a ‘customer-journey’.

We need to remember too that all of those ‘external’ stakeholders will be looking ‘Outside-In’, from their perspectives, in context of their needs, rather than solely for the service’s own ease and benefit. It’s at this point that we need to recognise that ‘efficient’ and ‘reliable’ and the like will start to have multiple meanings, often in conflict with each other… – hence why checklist-frameworks such as Nigel Green and Carl Bate’s VPEC-T (Values, Policies, Events, Content, Trust) have very real value here:

Yet there’s another aspect to ‘Outside-In’, with stakeholders who may not have transactions as such with the service, but do still have direct interactions with it. We might summarise this as the direct context for the service:

The stakeholders here are also looking at the service ‘Outside-In’, each in their own ways, but with direct impacts on the service and its relations with the ‘outside-world’. These stakeholders include regulators, for example, or complaints-arbitration bodies, who define the context for ‘fair pricing’ and ‘fair relationships’ with the transaction-stakeholders. They include recruiters, trainers, analysts, journalists and many others who interact rather than transact with the service. They include employees as employees – particularly those elsewhere in the organisation that operates the service. And, of course, there are ‘the competition’ – where such competition is relevant, which it isn’t in some types of context.

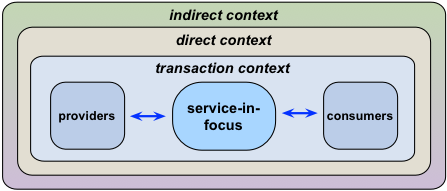

Further out again, there’s the set of perspectives that form the ‘Outside-Out’ view of the enterprise – in essence, the shared-story that would continue onward even if the service-in-focus did not exist. Stakeholders here would not have any direct transactions with the service as such, and what interactions they might have with it, or to it, or around it, or whatever, are kinda sideways-on, or more indirect – hence probably simplest to describe this as the indirect-context for the service:

Out here there can be a very wide range of stakeholders: government in general, for example; communities within which the service operates; the families of employees and others; non-clients, who are in the same shared-enterprise but don’t or can’t transact – because they’re in a different country, for example – and anti-clients, who are in the same shared-story but vehemently disagree with how the service operates within it. Each of those groups has their own distinct and disparate drivers, their own relationships with the service and the shared-story: the one thing they have in common is that they’re potentially affected by the service, and can potentially affect it in turn – a fact that we ignore at our peril…

The key point is that that structure – the service-in-focus, and those three layers of context – applies in every case, at every level, regardless of what we might choose as ‘the service-in-focus’. For example, if we place our focus on the organisation-as-whole – such as via its business-models, for example – we’d end up with a context-map that would look something like this:

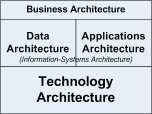

But if we were to do it just for a specific segment of the organisation, well down into the detail-layers of, say, the hardware-aspects of an IT-architecture, then the structure might look somewhat like the classic ‘BDAT-stack’:

In that type of case – typical for most classic IT-centric ‘enterprise’-architectures – the data and applications are, in essence, the transaction-context for the technology-hardware, and whilst the business-drivers provide the direct-interactions context.

(The indirect-interactions context rarely gets any mention in mainstream ‘enterprise’-architecture frameworks, which is one reason why they’re a lot less effective than most people seem to expect. Another is that the frameworks tend to hold the focus on efficiency above all else – which, however, is only one subset of overall effectiveness.)

Notice, though, that we can’t run the structure the other way round. The context is always broader than the service-in-focus – typically at least three steps broader, as in the ‘inside-in’ to ‘outside-out’ structure above. So in this case, ‘Business-Architecture’, ‘Data-Architecture’ and ‘Applications-Architecture’ form the context for the services-in-focus here, the ‘Technology-Architecture’. If we want to focus on data-architecture, applications-architecture, or business-architecture, we need to find the respective broader-context for each of those, as the respective services-in-context. What this warns us is that the ‘BDAT-stack’ should only be used for IT technology-architectures: it does not describe the context properly for anything broader than that.

Anyway, back to the practical point here:

- effectiveness comes from the intersections and interdependences of a swathe of ‘non-functional‘ factors, which we could perhaps simplify down to five key themes: efficient, reliable, elegant, integrated, appropriate

- enterprise is ‘a bold endeavour’ of some kind that, in essence, is what we choose to say that it is – there are typical sets of relationships that describe the context for an enterprise, but no fixed definitions beyond that

- enterprise effectiveness arises from paying proper attention to effectiveness in the enterprise

We might also note that simplicity is an attribute that arises perhaps most from and for elegance – the more people-oriented aspects of effectiveness. Hence why models and frameworks that are simple, yet not simplistic, can help a great deal in guiding that ‘proper attention to effectiveness in the enterprise’.

So let’s keep it simple.

Keep the models and frameworks simple.

Simple, yet not simplistic.

Everywhere in the enterprise.

Help people find their own effectiveness about creating effectiveness – effective for the needs of everyone in the enterprise.

More to follow on this, but best leave it there for now, I’d guess?