Link: http://weblog.tomgraves.org/index.php/2011/07/14/who-is-the-customer/

Who is the customer, in a business model?

That’s perhaps not as simple as it sounds. I’ve been working on a long how-to post on using Business Model Canvas in a non-profit context, and realised that even in a commercial context it can get very messy once we move outside of the relatively simple ‘world’ that the Canvas usually describes.

Business Model Canvas is great for describing a business-architecture. Its structure of Value-Propositions for distinct Customer Segments works very well at the abstract layer. Separation of Customer Segments also allows us to describe a complex multiway business-model, such as in the classic three-way newspaper case: content-providers paid to produce valued content; content-consumers who consume the content, often at no direct cost; and advertisers, who pay to have their messages embedded in the content.

Yet once we move from business-architecture to enterprise-architecture – the overview of the implementation and execution of that business-model – complexities can emerge that could render the business-model non-viable, or at least introduce new ‘gotchas’ that have to be resolved. To make it work, we need to ensure a good balance between business-architecture and enterprise-architecture. One clear example of this is that the meaning of ‘customer’ may be quite simple in a business-architecture, but can suddenly become a great deal more complex within the enterprise-architecture.

In the case typically described on Business Model Canvas, each Customer Segment represents a single type of ‘customer’: such as ‘content-provider’, ‘content-consumer’ and ‘advertiser’, in the newspaper business-model. We assume a single supply-chain for each of those customer-types. And yes, that often is what happens in the simple case of ‘consumer in the marketplace’ (a business-to-consumer or ‘B2C’ model).

But in a typical enterprise-type ‘B2B’ (business-to-business) model, that single ‘customer’ itself splits into multiple sub-customers. The person who buys, the person who deals with the order, the person who receives the item or service, the person who uses it, the person who verifies that it was ‘fit for purpose’, and the person who pays for it – they can all be different people, with different job-titles, all with different roles, responsibilities and authority, and in different parts of the client-organisation. To make our ’simple’ business-model work, we need to be able to identify and describe all of these sub-models, make sure that each one of them will work properly, and link all of them together into a unified whole.

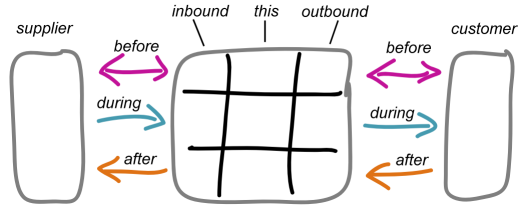

So whilst it’s valuable to sketch out the business-model on Business Model Canvas, this is where transferring that model onto Enterprise Canvas can help a lot. Enterprise Canvas draws clear distinctions between three types of flows: that which happens before, during and after the ‘main transaction’ of a business-model, such as its delivery of a product or service.

For example, most of the interactions with the buyer and the order-department take place before the main-transaction.

For example, most of the interactions with the buyer and the order-department take place before the main-transaction.

Interactions with the receiver and the user take place during the main-transaction – in effect define the main-transaction.

Interactions with the quality-check and payer (accounts-receivable) take place after the main-transaction.

This applies symmetrically both to ‘customer-side’ (for which we are ’supplier’) and to ’supplier-side’ (for which we are ‘customer’).

All of these are ‘customer-segments’ within the one simple Customer Segment on Business Model Canvas. Implementation and execution of the business-model means that all of these need to link together into a unified whole.

To do this, we’re likely to need distinct functions or capabilities within our enterprise-architecture to manage each of these flows and sub-transactions.

This gives us a structure from which to translate from Business Model Canvas.

We can also view that integration in terms of transitions over time. This is where another aspect of Enterprise Canvas – its linkage to the Five Element market-sequence or market-cycle – can help to clarify what needs to happen, when, and in what order, so as to make the business-model work.

The left-hand side on the diagram above is inward-facing, what we do to deliver our own value-proposition; the right-hand side is outward-facing, dealing with those ‘before-’, ‘during-’ and ‘after’-transactions with others. In an enterprise context, each node in the zigzag sequence often reflects a change of sub-customer, and hence a different type of ‘business model’ within the overall business-model. Each ‘customer’ is typically dealing with two or more ‘providers’ within our organisation, in order to keep the overall flow moving; and each ‘provider’ is typically dealing with two or more ‘customer’-types, too. Quite a juggling-act to make all of that link together: but that’s what has to happen, to make that business-model work in the real world.

The left-hand side on the diagram above is inward-facing, what we do to deliver our own value-proposition; the right-hand side is outward-facing, dealing with those ‘before-’, ‘during-’ and ‘after’-transactions with others. In an enterprise context, each node in the zigzag sequence often reflects a change of sub-customer, and hence a different type of ‘business model’ within the overall business-model. Each ‘customer’ is typically dealing with two or more ‘providers’ within our organisation, in order to keep the overall flow moving; and each ‘provider’ is typically dealing with two or more ‘customer’-types, too. Quite a juggling-act to make all of that link together: but that’s what has to happen, to make that business-model work in the real world.

A few more ideas to play with, anyway. ![]()

Over to you: comments/suggestions, anyone?