Link: http://weblog.tomgraves.org/index.php/2011/07/16/bmcanvas-for-nonprofits/

How do we use Alex Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas for the business of a not-for-profit organisation? Or, for that matter, the non-monetary aspects of a commercial organisation?

Over the past while have been asked by quite a few folks – Shawn Callahan, Alan Rodriguez, Robert Phipps and others – about how to use the Business Model Canvas in an NGO, government or other non-profit context. (Shawn’s client was a well-known international charity; I understand that Alan does architecture work for an independent but government-sponsored energy-trading exchange or something similar; Robert does data-architecture and other architecture-work in a government department in the social-services sector.) Hence seems that this might be a useful excuse to do a brief how-to, also linking Business Model Canvas to enterprise-architectures and business-process management via the Enterprise Canvas model.

‘Brief’ will likely be a relative term here, so continue after the break…

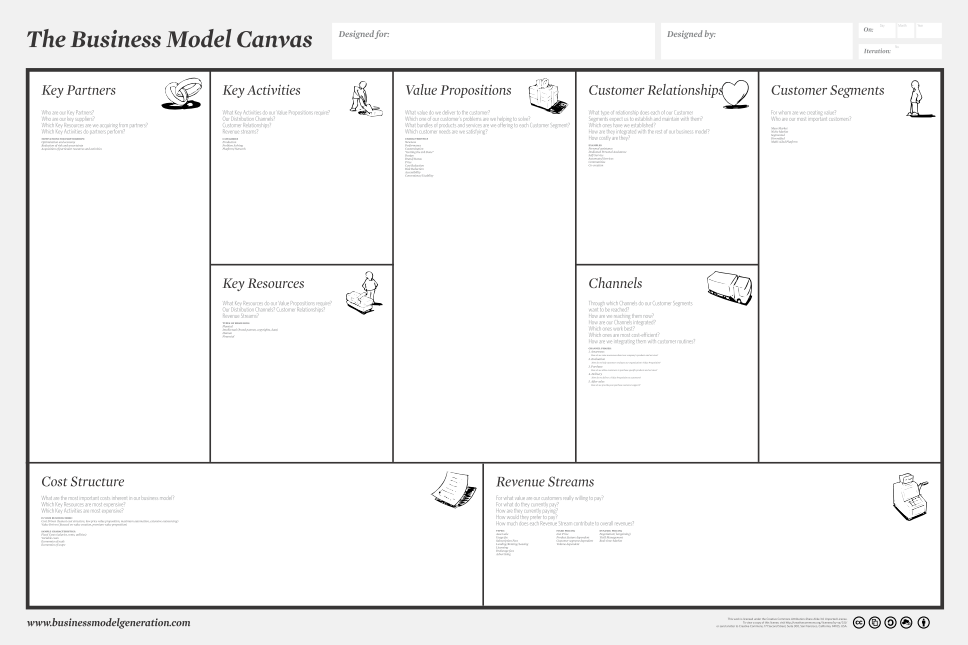

Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas – first described in the book Business Model Generation – has rightly become a staple for business-architecture worldwide:

Business Model Canvas [(cc) Osterwalder/Pigneur]

Business Model Canvas [(cc) Osterwalder/Pigneur]

Its strength is in its simplicity: it’s easy to describe a commercial business model in these terms, easy to understand, easy to engage people in business-model design and redesign. It’s also implemented in Osterwalder’s BMTbox iPad app, making it a powerful tool for ‘cafe conversations’ about business-models. For ‘conventional’ commercial business-models and their related business-architectures, it’s excellent.

Business Model Canvas for commercial organisations

Typically, we would start from either Value Proposition or Customer Segments, and move outward from there. What is our offer to the market? Who are the customers for this offering? and so on. The Business Model Generation book includes quite a wide range of standard strategic and tactical frameworks to get us started, such a Blue Ocean, Porter Value-Chain and so on.

We then wander around the model, iteratively, looking at the implications of each option, its impacts on everything else. For example, given these Customer Segments, through what Channels would we deliver our Value Proposition? Through what means would we create Customer Relationships to connect each of those Customer Segments to our Value Proposition? What returns – Revenue Streams – would we expect from each of our Customer Segments? What are the Key Resources we need to create and Deliver our Value Proposition? What are the Key Activities through which we would do this? What supplies do we need from others, or could we outsource some of those activities? – in other words, who would we need as out Key Partners? And what impact would each change have on our Cost Structure?

We can also support multi-segment business-models, such as the classic three-way free-newspaper-as-intermediary model used in modified form online by Google and the like, with its distinct value-propositions for three distinct customer-segments: the content-providers, who are paid to provide meaningful content for the ‘consumers’, who get the product for free, all of it paid for by advertisers, who get their messages embedded in the content.

And one of the great things about the model is that we can literally start anywhere. Round and round we go, trying out all the different options, building up a picture of the whole with wads of little Post-It® notes and scrawled connection-lines.

[An aside: from an enterprise-architecture perspective, one of the really serious limitations of the current version of the BMTBox app is that it doesn’t support those connection-lines – in fact to me, as an enterprise-architect rather than solely a business-model designer, that one absent-feature can sometimes render the app itself almost useless in practice. I had a long argument with Alex about this during the early development stages of the app, and lost: oh well, it is his app, after all. ![]() I didn’t succeed in explaining that whilst the connection-lines are implicit on the physical Canvas – because people simply draw them in as required with a whiteboard-marker or whatever – they need to be explicit on an app, especially for any kind of multi-segment model. The point is that whilst the ‘boxes’ on the model describe the activities and resources, in architecture we’re every bit as concerned with the ‘lines’ – the flows that connect between the ‘boxes’. I gather that the BMTBox app will eventually support explicit connection-lines: so if more of us can nag Alex about this, perhaps we can get it to happen sooner? – because it is essential for architecture-work, as will become clear later.]

I didn’t succeed in explaining that whilst the connection-lines are implicit on the physical Canvas – because people simply draw them in as required with a whiteboard-marker or whatever – they need to be explicit on an app, especially for any kind of multi-segment model. The point is that whilst the ‘boxes’ on the model describe the activities and resources, in architecture we’re every bit as concerned with the ‘lines’ – the flows that connect between the ‘boxes’. I gather that the BMTBox app will eventually support explicit connection-lines: so if more of us can nag Alex about this, perhaps we can get it to happen sooner? – because it is essential for architecture-work, as will become clear later.]

Change the building-block labels for non-profit organisations

Yet there are practical problems that arise as soon as we move outside of a commercial scope. There is still always a ‘business model’ – the means by which the organisation achieves its aims, ‘the business of the business’. Most of the ‘left-hand side’ of the model in Business Model Canvas is much the same in a for-profit and not-for-profit context, but the ‘right-hand side’ is often radically different in a not-for-profit context, where terms such as ‘Revenue Streams’, ‘Customer Segments’ or even ‘Value Proposition’ may make little apparent sense. So for a non-profit, that’s the first thing we need to fix.

This part isn’t hard. The BMTBox app does allow us to change the building-block labels as appropriate. And it’s straightforward enough to hack the standard BMCanvas template: Osterwalder generously released it under a Creative Commons licence, so it’s freely available in various formats such as PDF and PPT. (The BMTBox allows us to edit the labels, too.) Given that, we can change the labels to whatever we might need. For example, for Shawn’s strategic-review for a large charity, a few months back, we changed the labels and the supporting-text as follows:

- Customer Segments to Co-creators (using CK Prahalad’s term ‘Co-creators‘ as a generic for all ‘provided-to’ relationships and roles)

- Customer Relationships to Relations (generic to include non-customer relationships)

- Cost Structure to Value-streams – outlay and costs (to include non-monetary costs, such as investment of effort or potential costs to reputation etc)

- Revenue Streams to Value-streams – returns (to include non-monetary value, in particular success in terms of the charity’s social/environmental aims)

In essence, the process for business-model development remains much the same as above: we identify the groupings of Co-creators, and the offerings (Value-propositions) to those respective groupings of co-creators, assessing Costs and Returns in the respective forms of value. We go through the same iterative assessment: for example, how do we connect with the respective groupings – our Relations with them? Via what Channels do we deliver the respective offerings? What are Key Resources and Key Activities do we need, to make this happen? Which Key Partners do we need, assisting in which activities and resources? Round and round, iterating through all of the different options.

This is enough for a first-level review of a non-profit business-model. Yet this still doesn’t resolve the fact that some of the core concepts behind the respective business-models can be very different to those in a commercial context: and in those cases, we do need to go deeper.

[Another aside: It’s perhaps important to remember here that Business Model Canvas is designed for, and optimised for, one specific purpose: developing and mapping business-models for commercial business enterprises. It is a very powerful tool for that purpose. The moment we move outside of that commercial scope, though, or if we try to use it for enterprise-architecture rather than business-architecture, we need to remember that we’re asking the Canvas to do something that it wasn’t designed to do. In other words, those adaptations that we need to do here are our own responsibility, not Alex’s – and we can’t complain about it, either!]

Connecting to vision

For government or other non-profits, the emphasis on monetary revenue is obviously an important limitation for the Business Model Canvas. Yet in going deeper, we soon discover that the Canvas has several other structural assumptions that really start to get in our way. The first of these relates to enterprise vision.

In effect, Business Model Canvas assumes that the vision – the ‘core question’ – that drives the business-model will always be ‘how do we make money?’ Hence its Value Proposition will always tend to be forced into those terms: the ‘value’ is qualitative – better, cheaper, faster – but is ultimately expressed as a monetary value. (The BMTBox app at present only allows value to be expressed in monetary terms.)

In enterprise-architectures, though, we need to lift the understanding of ‘value-proposition’ up a notch or two. (This is actually true for commercial organisations as well as government or non-profit.) We need to know what ‘value’ means within the shared-enterprise, before it gets converted to monetary terms – if it can be converted into those terms at all. Before we go any further, we need a better understanding of that shared-vision and the values that derive from it. (See, for example, the slidedeck ‘Vision, role, mission, goal‘, and the summary in slide 20 in this presentation.) In those terms, the organisation exists to satisfy some aspect of the tension between the desired aims and what actually exists at present:

Chris Potts’ aphorism is a useful reminder here: “customers do not appear in our processes, we appear in their experiences”. The vision describes the reason to connect with the organisation, and the expectations for those experiences. It’s not just a supply-chain about ‘bigger, faster, cheaper’: instead, the meaning of value – ‘that which is valued’ – is defined by the shared vision, and everything that flows around the ‘value-network’ of the shared-enterprise is assessed both in terms of its direct value to the next person in the flow, and in terms of the values of the enterprise. In that sense, everything in the enterprise is a service that works towards the same shared desired-ends.

That then has a two-fold impact on the model’s Value Proposition.

First, the focus of the value-proposition shifts to how this activity or product or service delivers value to the entire shared-enterprise – not solely about ‘bigger, faster, cheaper’ and the like. It is first about how it contributes to the non-profit’s aims, or the government-department’s Results Logic [PDF], and then the qualitative concerns such as ‘bigger, faster, cheaper’ – in that priority order. The concept of offer as ‘value-proposition’ remains: but if it does not demonstrably contribute towards the enterprise-vision, it will not be perceived as a ‘value-proposition’.

Second, it implies that the service needs some kind of value-proposition for every stakeholder-group in the shared-enterprise – even those with whom it does not have direct transactions. For a non-profit, reputation and trust are the keys here – particularly in relation to non-clients or, especially, anti-clients, who will hold the organisation to account on those values. For a government department, these will be citizens and voters, who may not have direct interactions with the department, but who will certainly influence on or react to nominal policy – even as misreported in the media. The ‘market model’ is a useful way to summarise the relationships here:

The related ‘market cycle’ helps to summarise the dependencies:

The related ‘market cycle’ helps to summarise the dependencies:

Relationships with non-clients and anti-clients connect primarily with values, policies and trust – the latter in essence being a metric of the organisation’s perceived alignment with its declared or implied vision of the enterprise.

Business Model Canvas sort-of deals with this on the ‘Customer’ side: if we think of non-clients and anti-clients as ‘customers’ of the idea or ideals that the organisation purports to represent, in its association with the shared-enterprise, then we could see Customer Relations as taking on that role of interaction, yet without ever reaching the point where main-transactions occur. The real complication with the Canvas for this, though, is that it’s asymmetric: there’s no equivalent of Customer Relations on the ’supplier-side’ of the model. It’s at this stage in modelling that we may be forced to part company with Business Model Canvas.

Asymmetry of service

The structure of Business Model Canvas is somewhat asymmetric: its focus is firmly on the relationship between the organisation and its Customer Segments, without much attention paid to the ’supplier-side’ other than the reference to Key Partners. That’s often a fair-enough short-cut in many types of commercial business-model. Yet even in business, a business-model can make-or-brake on the supply-side as much as on the customer-side; and in non-profits and government the distinctions between ‘customer’ and ’supplier’ are rarely clear-cut.

Instead, it’s often best to think solely in terms of value-flows – before, during and after each main-transaction – and then identify the respective ‘customer’ or ’supplier’ roles after that assessment. In this view, the organisation is and/or provides services that deliver value in relation to the aims of the shared-enterprise – and we model the service in terms of the value-flows between players. A ’supplier’ is thus another service from whom we primarily receive some form of value in the main-transaction flow; and a ‘customer’ is another service within the enterprise to whom we primarily provide value, much as described in the market-cycle. In that sense, ‘customer’ or ’supplier’ is not a person or organisation, but a contextual role that any person or organisation may take – and may switch between those roles, according to context.

We can then partition our own service in terms of those relationships, on the ’supplier-side’, ‘customer-side’, and our own activities for value-creation and value-delivery.

We can then partition our own service in terms of those relationships, on the ’supplier-side’, ‘customer-side’, and our own activities for value-creation and value-delivery.

Given this, we can then do a cross-map from Business Model Canvas to this extended ‘Enterprise Canvas‘.

Given this, we can then do a cross-map from Business Model Canvas to this extended ‘Enterprise Canvas‘.

Note too that we place a strong emphasis on the flows between our service and the ’supplier’ and ‘customer’ services – which we can’t do so easily in the ‘block’ structure of the Business Model Canvas. (This is where the lack of support for flows in the BMTBox app becomes a serious shortcoming in practice.) Nigel Green’s VPEC-T – Values, Policies, Events, Content, Trust – is a particularly useful framework through which to assess those flows (though see the post ‘More on “Not-Quite-VPEC-T”‘ for some caveats on how to use that framework with Enterprise Canvas).

Investors and beneficiaries

Finally, there’s a collection of relationships that are usually implied or glossed-over in a commercial business-model, but are often extremely important on non-profit and government business-models: the relationships with investors and beneficiaries.

Investors are a bit like suppliers, but the main flow goes the opposite way: they put value into the service, rather than retrieve it on the backchannel (the ‘after’ flow). We often need investors to ‘prime the pump’, putting value in so as to start up the relationships with the main-transaction suppliers. Further up, they also help to provide credibility – ‘trustworthiness’ – to establish the respect of prospective clients, non-clients and anti-clients.

Beneficiaries are a bit like customers, but again the main flow goes the opposite way: they retrieve value from the backchannel, rather than putting it in, as customer-roles do.

In Enterprise Canvas, we model these as roles attached to the respective side of the backchannel – investors on the ’supplier-side’, beneficiaries on the ‘customer-side’.

An investor is anyone who invests some form of value into the organisation, in terms of the values of the shared-enterprise. So this includes employees, who invest their time and commitment; it includes the community within which the organisation operates. For a non-profit, it includes donors, volunteers, fund-raisers and the like; for a government-department, it includes, voters, citizens, often also related government-departments that work kind of in-parallel rather than with our own department. It’s a supplier-like relationship, but that which is supplied is some kind of value, usually in a fairly ‘pure’ (abstract) form.

An investor is anyone who invests some form of value into the organisation, in terms of the values of the shared-enterprise. So this includes employees, who invest their time and commitment; it includes the community within which the organisation operates. For a non-profit, it includes donors, volunteers, fund-raisers and the like; for a government-department, it includes, voters, citizens, often also related government-departments that work kind of in-parallel rather than with our own department. It’s a supplier-like relationship, but that which is supplied is some kind of value, usually in a fairly ‘pure’ (abstract) form.

A beneficiary is anyone who retrieves some form of value fron the organisation, in terms of the values of the shared-enterprise. For example, a community may gain a sense of pride, of satisfaction, or simply the fact of having gainful employment within a money-based economy.

In this context, it’s often very important to not view ‘value’ solely in monetary terms – otherwise many of the business-crucial investor or beneficiary relationships will not make sense, or may not even be visible at all.

One of the key concerns in modelling these relationships is that two types of relationships do need to balance somehow – otherwise anti-client problems will be created or exacerbated. There is often additional complexity in that investors and beneficiaries are not necessarily the same people, and that the forms of value in each flow may be different – for example, a community invests effort and trust, and receives a stronger sense of community in return. Again, the VPEC-T frame provides a very useful set of ‘lenses’ through which to view and assess these flows and relationships.

There’s no obvious means to model these relationships in Business Model Canvas as such: you would either do so by attaching the respective extra ‘blocks’ below Cost Structure (investors) and Revenue Streams (beneficiaries) respectively. Another, perhaps more practical option is to do preliminary modelling in Business Model Canvas, and switch over to Enterprise Canvas once the limitations of the former are reached.

Summary

Business Model Canvas, in its current form, is a very good framework on which to develop business-models for commercial organisations. It’s not such a good fit for the requirements of business-modelling for non-profits and government departments: the main limitations are in its built-in assumptions about the nature of value, its inherent asymmetry in terms of relations with customers versus suppliers, and its lack of support for modelling relationships with investors and beneficiaries. The Business Model Canvas has huge advantages in terms of simplicity and ease of understanding, whilst the Enterprise Canvas model provides a useful and largely-compatible alternative for the aspects of modelling that Business Model Canvas cannot reach.

[In the next post, I’ll describe how to use Enterprise Canvas to extend a business-model in Business Model Canvas into the more detailed-modelling needed for enterprise-architecture assessments of implementation and execution of the business-model.]