Link: http://weblog.tetradian.com/2015/05/22/idea-parenting/

I’d often wondered why I always seem to have such a visceral response to hearing a woman say “I don’t work, I’m only a mother”. What do you mean by “only”? – why would anyone deride it so? And what do you mean by “I don’t work”? – it’s some of the hardest work there is!

Yet it’s only in the last few days that I’ve realised why I react so strongly to that strange self-denigration: it’s because much the same applies to my own work too.

To my sadness, I’ll admit, I’ve never been a literal parent. Yet almost all of my own work is about a very close analogue: idea-parenting.

Some years back I wrote here about the somewhat-similar notion of ‘ideafarming‘. That too is a lot of work, but it’s still a somewhat passive process: we give the ideas the best conditions to grow in, but otherwise leave them to grow up on their own. Projects and short-term products are often a bit like that, I guess: once they’re finished, harvested, they’re done.

Yet some ideas need a more active form of nurturing – ideas for tools and suchlike that would in turn take on an active life of their own, interacting with the world much like an animal – or a child, of course. That’s where we shift from farming of ideas, to something more like parenting.

This isn’t just about conceiving of ideas. (Conceiving is easy: ask any rabbit…) It’s what happens after conception of ideas that matters here.

There’s first a period of gestation, where the first tiny germ of an idea develops quietly, invisibly, into an embryo, and then onward towards a viable offspring. This may take place somewhat out in the open, as with birds; or in a fully hidden space, as with placental animals. It may take mere days, maybe a handful of weeks at most, like rabbits; or long, long months or years of gestation, like an elephant. It may demand no action as such from the parent, as with mammals; or active protection, as with nesting birds: but either way that stage of nurturing still takes real energy and effort.

And during that gestation, some ideas may die before they’re even born. They may be snatched away, disrupted, broken, as in a small bird’s nest after a raid by a magpie or a snake; they may be reabsorbed into nothingness, as a rabbit may do to its embryos when times are tight; they may simply be lost, without anyone ever really knowing that they’d existed. Either way, sad, yet a loss that we somehow have to accept.

Then the ideas are born, become active and visible, out into the open world. They might kinda hatch themselves, like a chick out of an egg; the birth may be easy, the infant idea almost absurdly small, much as with kangaroos and other marsupials; or the infant large, and the birth hard, much as with so many mammals – including humans, of course. But either way, that’s when the real work begins.

After the start, probably the hardest work in idea-parenting is about socialisation of ideas:

– To be ‘useful citizens’, ideas and tools need to incorporate self-discipline, consistency, clarity; we need to know that they can be trusted to do what they say they’re going to do.

– They need learn how to ‘play nicely’ with other ideas, work together, support others, listen, suggest other options, not hog the space or the limelight.

– They need to find their own place within the world of ideas and tools – which, courtesy of affordances and other serendipitous interactions with the real world, may not be where we’d expected them to end up at all, but yet still turns out to be right.

If we’re not careful, some ideas can end up like street-kids, lost, abandoned, angry, always at risk of turning on their own creators, or lurching after any other fad that seems to offer some form of illusory hope.

If we’re not careful, some ideas can get stuck in the screaming selfishness of ‘the terrible twos’, becoming as dysfunctional and destructive as those behind neoliberalism and the like – so well summarised by the tagline for the film ‘The Riot Club‘, as ‘Filthy. Rich. Spoilt. Rotten.’

If we’re not careful, some ideas may never even get that far…

It’s a lot of work. A lot of work.

But here, as described in the previous post, we hit up against a fundamental problem. Much as with real parenting, this idea-parenting is barely acknowledged as work, and hence almost no-one within this so-dysfunctional culture of ours seems to realise that it somehow needs to be paid for, just like everything else.

In a way, real parents get it somewhat easier in that sense. What they do is still not much acknowledged as ‘work’ – sometimes even by the parents themselves, as per that quote with which we started – but at least there’s usually some form of payment, even if only from the state, as child-benefits or welfare or whatever. But for idea-parenting? – nothing. Always Somebody Else’s Problem, it seems…

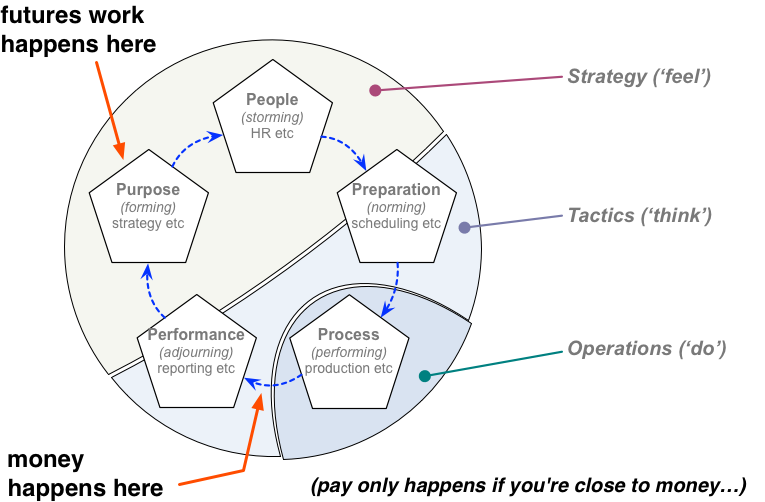

And yes, in effect it’s another form of the futurist’s dilemma:

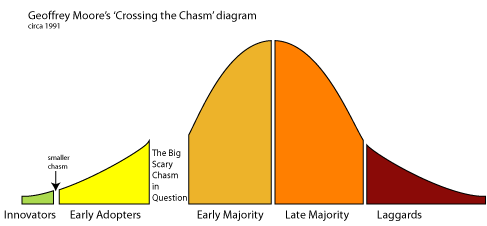

Yet for the context of idea-parenting, it’s actually a bit more subtle – and nastier, in terms of routine ‘dirty-tricks’ – than that diagram implies. To make sense of what goes on, it’s probably useful to cross-compare the above with another well-known diagram from Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm:

The first stages of idea-parenting, as one might expect, map closely to the Innovators phase of that model. And because just about everyone in that space is an Innovator, little if any money will change hands. In essence, everyone’s in the same boat, and everyone is a peer for everyone else: no-one has much money, and the whole space operates more like a sharing-economy where the real ‘currency’ is mutual assistance and mutual respect.

There’s then what Geoffrey Moore describes as ‘a smaller chasm’ to cross, to the Early Adopters, where the idea starts to stand up on its own feet and be able somewhat to look after itself. Metaphorically, a bit like the teenage years, or secondary-school, where the idea starts to take on its first real jobs under real-world conditions (or somewhat-sheltered conditions, to be more exact, but still definitely real-world by now). There might be a bit more money that changes hands here, but it’s still not much, because of the trade-off to get real-world experience. (Again, think of the kind of money that changes hands for a metaphoric newspaper-round or the equivalent.) It’s something – but it really doesn’t cover much of the costs that have been incurred so far.

At the end of that phase, we hit Geoffrey Moore’s ‘Big Scary Chasm’ – with even more costs to get the idea ready for the hoped-for big-time, the Early Majority, who might have pockets deep enough to start contributing towards all those past accumulated costs.

But…

…that’s when our culture’s delightful parasites swoop in:

– the metaphoric equivalent of “yes, you can work here as an unpaid intern, and, by the way, everything you do and have done before now becomes our company’s ‘intellectual-property’”.

– the metaphoric equivalent of “just sign here, and here, and here – we’ll do all the rest, for a small service-fee, of, oh, only 90% plus expenses…”

– the not-so-metaphoric equivalent of seeing someone steal all of our multi-year work and rebadge it as their own, without paying a single cent towards any of the previous costs, because, “well, ‘everyone knows’ that your idea is obvious now, don’t they?”

(I’ve mostly managed to avoid the first two, but it’s not long ago that I had the un-joys of hearing how a big-consultancy VP got a standing-ovation at a conference, and big-consultancy gigs to follow, on the basis of what was just a rebadged merging of my work with someone else’s. I know it was my work that had been purloined there, because that person used a specific term that had otherwise only occurred in some of my published blog-posts. The phrase ‘We Are Not Amused’ applies, perhaps?)

So it’s not just that “pay only happens if you’re close to money”, as per the Futurist’s Dilemma: it’s perhaps even more that as soon as there’s the slightest hint of the possibility of payment, the parasites and scavengers appear – and they don’t leave a single scrap for anyone else.

Exploitation of ideas, indeed – but usually in the worst possible sense: kinda like watching our children dragged off into slavery and servitude, destroying all of our hopes for their future – and for our own future too. Sickening, frankly: but such are the deep dysfunctions of our sick society. Oh well…

Idea-parenting is darned hard work, even just in the work itself. But that work is made much, much harder because so few people acknowledge it as work, and hence fail to understand why it needs to be paid for somehow, exactly as for any other work. And the work is made much, much harder again by the way in which our culture not allows the parasites free-rein, with almost complete impunity, but in many cases actively supports them in doing so – even actively penalising the idea-parents on the parasite’s behalf.

The word ‘dispiriting’ doesn’t even begin to describe how that all feels at times…

But yes, it does kinda explain that visceral response to the phrase “I don’t work, I’m only a mother” – because for those of us whose life-work revolves around idea-parenting, the iniquities and injustices we face are, too often, almost too much to bear.

Best leave it there, I guess: over to you for comment, if you wish?