Just how much of a law is Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety? Our answers to that question – and likely there’ll be many of them – are fundamental to how we handle key architectural concepts or requirements such as management, control, certainty (or lack of it), complexity, disruption and much, much more.

Okay, first, the nominal law itself, as summarised in Wikipedia:

If a system is to be stable the number of states of its control mechanism must be greater than or equal to the number of states in the system being controlled.

Or, as summarised by Stafford Beer, in relation to variety in viable systems:

[variety is] the total number of possible states of a system, or of an element of a system … the logarithmic measure of variety represents the minimum number of choices (by binary chop) needed to resolve uncertainty.

In short, control is possible in a context only if the controlling mechanism can manage a range of variety at least equal to or greater than the variety inherent in the context itself.

Which, if we think about it for more than a few seconds or so, tells us that absolute control is all but impossible in the real-world, because there are so many real-world items – nuclear fission, to give one well-understood example; or customer-service, to give another less-well-understood example – that present near-infinite variety or uncertainty.

Hence, in short, control is a myth – a futile fantasy of wishful-thinking. Oh well.

But just wait a minute, you might say – how come we seem to have control of most things for much or most of the time? Which is true enough – sort-of. And it’s in that ‘sort-of’ that things get kinda interesting… and where those answers to the ‘law-ness’ of Ashby’s Law get kinda important.

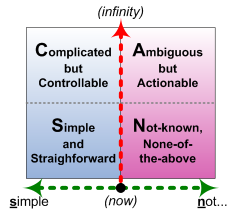

Quick background to all of this is that a couple of days ago I was trying to explain to a colleague how to use the SCAN sense-making/decision-making framework:

In particular, I was exploring with him the conditions and contexts in which we switch from side to side of the Inverse Einstein Test (the central red dividing line in the graphic above) – the point at which doing the same thing leads either to the same results (left side: Simple/order) or to different results (right side: Not-known/unorder).

And the key realisation is that, in the real-world, that boundary-condition will itself keep moving around. Sometimes doing the same thing will give the same results – in other words, what we might typically think of as ‘control’. And sometimes it won’t give the same results – which means we’re not ‘in control’. Despite doing exactly the same things, and following the same nominal ‘laws’. Tricky, that…

So sometimes we’re in control. And sometimes we’re not. Of the same nominal context.

Or, to put it another way round, there’s variety in the variety of the context.

Or, in yet another way to frame it, Ashby’s Law is recursive: if it’s a true law, it has to apply to everything – including itself.

Which suggests in turn that we perhaps need to re-think the variety of a system as being more like the uncertainty of weather, rather than some kind of fixed numeric value:

- Variety is not a state, but dynamic, itself varying over time.

Hence sometimes there are periods of calm, when the variety in the system is low. This is what gives us that so-desirable illusion of ‘control’.

Sometimes there’ll be long periods of calm, when we get lulled into thinking that our ‘world’ – whatever that might be – will stay the same forever.

And then sometimes it’s ‘stormy weather’, when we get a firm reminder that ‘control’ is indeed an illusion….

Sometimes those periods of stormy-weather can go on for a long, long time, in which nothing seems stable or certain – the kind of ‘world’ we’re often dealing with in enterprise-architectures right now, in fact.

So whilst in principle Ashby’s Law would always hold, perhaps it might be useful to think of variety in a way analogous to weather-forecasting:

– Sometimes the variety-weather will be calm: in which case we can trot out all of those tried-and-tested management-methods, and be reasonably certain that they’ll work well. For the while, until the variety-weather changes.

– Then sometimes it turns stormy: in which case we need to acknowledge that those ‘control’-based methods won’t work in that context, and we need to shift over to the different disciplines of design-thinking and the business-anarchist and suchlike. For the while, anyway.

The trick is to watch the variety-weather, so as to know when to change methods. And at the present time there doesn’t seem to be any systematic approach to this: skilled business-folk do it more by ‘feel’ than by anything else, it seems.

So perhaps it’s time for a new science (or craft, or technology, or some such) of ‘varietology’, or something like that – an equivalent of meteorology, to monitor the variety of the variety-weather in our business context?

And if so, what would it look like? What are the key factors behind the variety of the variety? What forms do they take? – how do we experience this variety-weather? And how could we make sense of all of those factors – or of the sense-making itself?

Comments / suggestions, anyone?